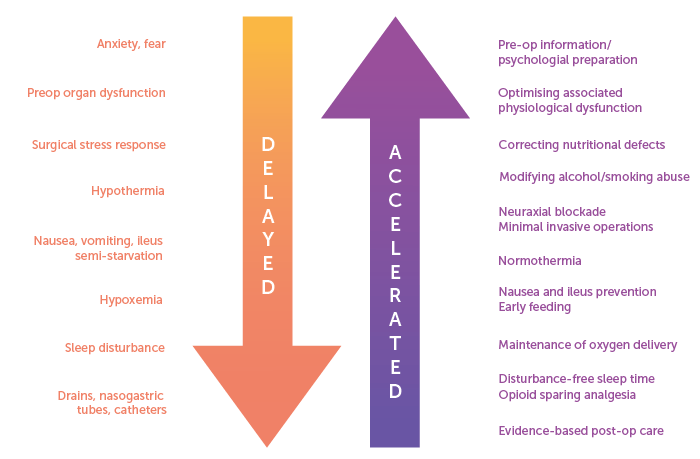

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is multidisciplinary, evidence-based approach to perioperative care of the surgical patient. It was initially developed in 1995 by Henrik Kehlet, a Danish surgeon, and aimed to minimise surgical stresses and maintain physiological homeostasis1.

Figure 1. Multimodal interventions in the ERAS pathway as outlined by Henrik Kehlet. Source: Kehlet H, Wilmore DW, Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002 Jun;183(6):630-41

This results in reduced morbidity, faster recovery and quicker return to baseline function. Subsequently, the ERAS Society has developed ERAS guidelines specific to gynaecology oncology2. This article explores components of perioperative management through three key management aspects: pre-operative, intra-operative and post-operative.

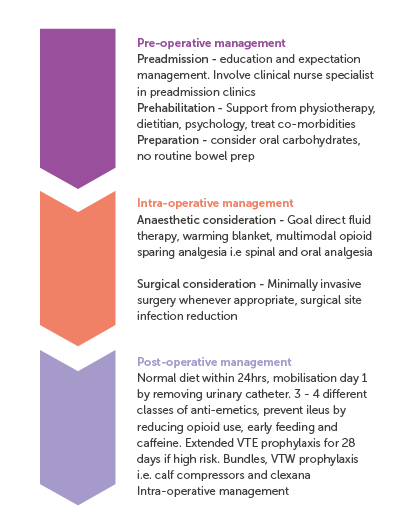

Figure 2. Summary of gynaecology oncology ERAS pathway.

Adapted from: Sidhu, Lancaster, Elliott, Brand, 2012

Pre-operative assessment (3Ps) – Goal = optimisation

1. Preadmission

This involves patient education and counselling in order to set expectations about surgical and anaesthetic perioperative care3. This has shown to reduce patient anxiety, facilitate early discharge and reduce post operative pain and nausea4.

2. Prehabilition

Prehabilition initiatives are relatively new in the field of gynaecologic oncology and have not been standardised.3,5 Prehab ensures patients are physically and mentally prepared before undergoing complex surgical procedures5

Strategies involve a multidisciplinary approach:5

- Physiotherapy to improve physical capacity, reduce risk of sarcopenia and expedited recovery to baseline

- Nutritional assessment to identify malnutrition and engage dietetic support

- Psycho-oncological support should be offered to empower patients and educate on coping techniques in preparation for surgery and recovery

Best supportive therapy optimises patients so that they are at their best health before surgery6. This includes:

- Controlling symptoms: preoperative pain management, drainage of pleural effusions or ascites

- Correcting any metabolic imbalances

- Improving overall health conditions: treating co-morbidities, smoking and alcohol cessation

3. Pre-operative preparation

Oral carbohydrates administered 2-3 hour prior to anaesthetic induction has been shown to reduce post operative insulin resistance, expedite bowel function restoration and is associated with shorter hospital stays.7 Most studies included oral beverages containing 50g of carbohydrates. It is unclear if a specific carbohydrate drink is necessary, or whether oral clear fluids would suffice. Results are extrapolated from other abdominal and pelvic surgical data as currently there are no specific gynaecological oncology data.

Routine bowel preparation is discouraged due to the lack of evidence of benefit3. If a bowel resection is thought likely, then results from a meta-analysis would favour combination of oral antibiotics (erythromycin) with mechanical bowel preparation to lower surgical site infection risk8.

Intra-operative management – Goal = Stress minimisation, maintain optimal surgical conditions

1. Anaesthetic considerations

Optimal fluid management through goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) utilises parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, cardiac output to titrate intravenous fluid, inotropes and vasopressor therapy. GDFT is associated with a reduction in morbidity, hospital length of stay, intensive care length of stay and time to passage of faeces9.

Maintaining normothermia by use of air blanket devices, warmed IV fluids and warming mattress to avoid hypothermia which is associated with increased surgical site infections and cardiac events3.

Multimodal opioid sparing analgesia has been shown to improve quality of life after surgery by minimising side effects from opioid use3. This may be achieved through a combination of non-opioid oral medications and regional anaesthesia or incisional injections with local anaesthetics.

2. Surgical considerations

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has been shown to reduce blood loss, length of stay, reduce pain and expedite return to normal daily activities3. It should only be selected where appropriate and should not compromise oncological outcomes. Long-term outcomes in MIS have been found to be similar to open procedures for endometrial cancer but not for early-stage cervical cancer10,11.

Surgical site infection reduction bundles include antimicrobial prophylaxis (first generation cephalosporins), chlorohexidine-iodine-alcohol skin preparation, preventing hypothermia, reducing hyperglycaemia and avoiding surgical drains especially in the subcutaneous level3.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention recommendations include dual prophylaxis with mechanical prophylaxis such as sequential compression devices and chemoprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin while inpatient.12 Chemoprophylaxis should continue for a total of 28 days following abdominal or pelvic surgery for cancer12. Currently, there is low quality and inconclusive evidence for the use of direct-acting oral anticoagulants as alternative thromboprophylaxis to LMWH or heparin.

Post-operative care – Goal = expedite recovery and return to baseline

Early oral nutrition encouraged, ideally within the first 24 hours after gynaecological cancer surgery to support return of gut function3.

Early mobilisation reduces post operative complications such as VTE and post operative ileus. This can be facilitated by early removal of indwelling catheter, usually removed morning after surgery if suitable. Early referral to physiotherapy and prompt identification of patients who will require short-term rehabilitation is paramount to support recovery3.

Extra considerations include:

Minimising post operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) by avoiding volatile anaesthetics and nitrous oxide, using regional anaesthetics, and emphasis on multi-modal opioid sparing analgesia. At least 3-4 anti-emetics of different classes should be offered13.

Prevention of post operative ileus should be a priority following a laparotomy. Interventions to encourage return of gut activity includes reduce opioid use, early feeding, early mobilisation, gum chewing and drinking coffee3.

Limitations of ERAS guidelines

The ERAS guidelines are based on best available evidence in the current literature. Nevertheless, there are certain interventions where high-quality evidence was unavailable. It is important to recognise that each element is not mandatory and needs to be adjusted according to individual patient and unit circumstances. However, the greater the adherence to most of the guideline elements, the greater the potential benefit to the patient.

Challenges to implementation of ERAS

Despite the documented advantages of ERAS, it has not been universally adopted due to perceived barriers in implementation14. These barriers include lack of buy-in from clinicians and hospital leadership, economic and resource constraints such as access to training to implement, and gaps in high quality evidence for certain ERAS recommendations.

It is crucial that implementation of an ERAS program begin with a multidisciplinary team who leads the development of an ERAS program specific to the needs of a particular unit15. It should be led by, and include, a surgeon, an anaesthetist, a pain specialist and an experienced nurse who are then responsible for obtaining buy-in from other team members. Subsequent audit of outcomes is essential to make appropriate adjustments as needed and close the implementation loop.

References

- Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002 Jun;183(6):630-41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00866-8. PMID: 12095591.

- Nelson G, Kalogera E, Dowdy SC. Enhanced recovery pathways in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Dec;135(3):586-94.

- Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, Glaser G, Altman A, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 May;29(4):651-668.

- Booth K, Beaver K, Kitchener H, et al. Women’s experiences of information, psychological distress and worry after treatment for gynaecological cancer. Patient Educ Couns 2005;56:225–32.

- Schneider S, Armbrust R, Spies C, du Bois A, Sehouli J. Prehabilitation programs and ERAS protocols in gynecological oncology: a comprehensive review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020 Feb;301(2):315-326.

- Fotopoulou C, Planchamp F, Aytulu T, et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology guidelines for the peri-operative management of advanced ovarian cancer patients undergoing debulking surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:1199–206.

- Smith MD, McCall J, Plank L, et al. Preoperative carbohydrate treatment for enhancing recovery after elective surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;8.

- Chen M, Song X, Chen L-Z, et al. Comparing mechanical bowel preparation with both oral and systemic antibiotics versus mechanical bowel preparation and systemic antibiotics alone for the prevention of surgical site infection after elective colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Dis Colon Rectum 2016;59:70–8.

- Rollins KE, Lobo DN. Intraoperative Goal-directed Fluid Therapy in Elective Major Abdominal Surgery: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Surg. 2016 Mar;263(3):465-76.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, Lopez A, Vieira M et al. Minimally Invasive versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 15;379(20):1895-1904.

- Janda M, Gebski V, Davies LC, et al. Effect of Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy vs Total Abdominal Hysterectomy on Disease-Free Survival Among Women With Stage I Endometrial Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. 2017;317(12):1224–1233.

- Nigel S. Key et al. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. JCO 41, 3063-3071(2023).

- Gan TJ, Belani KG, Bergese S, Chung F, et al. Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2020 Aug;131(2):411-448.

- Bhandoria GP, Bhandarkar P, Ahuja V, Maheshwari A, Sekhon RK, Gultekin M, Ayhan A, Demirkiran F, Kahramanoglu I, Wan YL, Knapp P, Dobroch J, Zmaczyński A, Jach R, Nelson G. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in gynecologic oncology: an international survey of peri-operative practice. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Oct;30(10):1471-1478.

- Sidhu V, Lancaster L, Elliott D, Brand A. Implementation and audit of ‘Fast-Track Surgery’ gynaecological oncology surgery. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2012; 52: 371–376

Leave a Reply