Dr Quang Phu Ho could swear he could hear his heart pounding against his chest. If the slightest sound betrayed him, he would be discovered. He stepped lightly, making sure not to rustle any leaves as he navigated the jungle, protected only by the veil of night.

Quang had been born in Vietnam to a family of nine siblings. His childhood memories were painted with strokes of the Vietnam war. Now, at the age of 18, he had been conscripted into the army to liberate Cambodia from the Khmer Rouge. He had had his share of war. When he was given an order that his conscience would not allow him to follow, he decided he would leave that night.

Little did he know he would perfect the art of escaping in years to come. After leaving Cambodia, Quang was taken to a forced labour camp to pay for his desertion. He worked there for 16 months, clearing the jungle with bony hands – evidence of malaria and starvation. He tried fleeing twice, but was not successful, which only made things worse. Fearing for his life, his father decided to help. He would help his son get away, but this time from the country itself.

Quang’s father arranged a boat trip for his son. The small, cramped, leaking boat had more than 100 people on it sailing in an unknown direction. Quang spent the next five days aboard fighting a storm with no food and no water. On 23 December 1980, he docked in Malaysia and was allocated to a refugee camp.

“The camp was very crowded and there was not enough food for all of us, but I actually had a good time there. At least we knew we were safe and waiting for the future. Freedom at last,” shares Quang.

The refugee camp, however, brought a different kind of challenge: the waiting. “Everyone has a hope that a country will accept you. You see people coming and leaving and wonder when will it be my turn? A lot of my friends spent years there. Just waiting and waiting…”

Quang was lucky. After just four months, he was accepted into Australia. When interviewed by an Australian delegate as to why he wanted to go to Australia, with minimal English he said, “Australia has kangaroo”. He arrived at Sydney airport in 1981 with nothing but a pair of Qantas socks. A humanitarian organisation arranged for his accommodation and English schooling.

“I remember one of my teacher’s name was Christine, whom I have shown my respect to by naming my first daughter after her. Her English was fantastic. I studied with her for two months and decided to drop out. I liked learning, but I needed to pay for my boat trip and to help my family, so I went to look for a job. Christine was very angry and begged me to stay, but I needed the money.”

Since Quang’s English was not very good, he struggled to find a job. Finally, he landed two factory jobs. “The first one was a very horrible job. I stayed there three months. Then I got a job as a spray painter at Comalco Windows and Doors, which was slightly better. We worked 16 hours a day for seven days a week but I made good money, so I stayed.” Thanks to Quang’s work, five of his brothers were able to escape Vietnam and reunite in Australia.

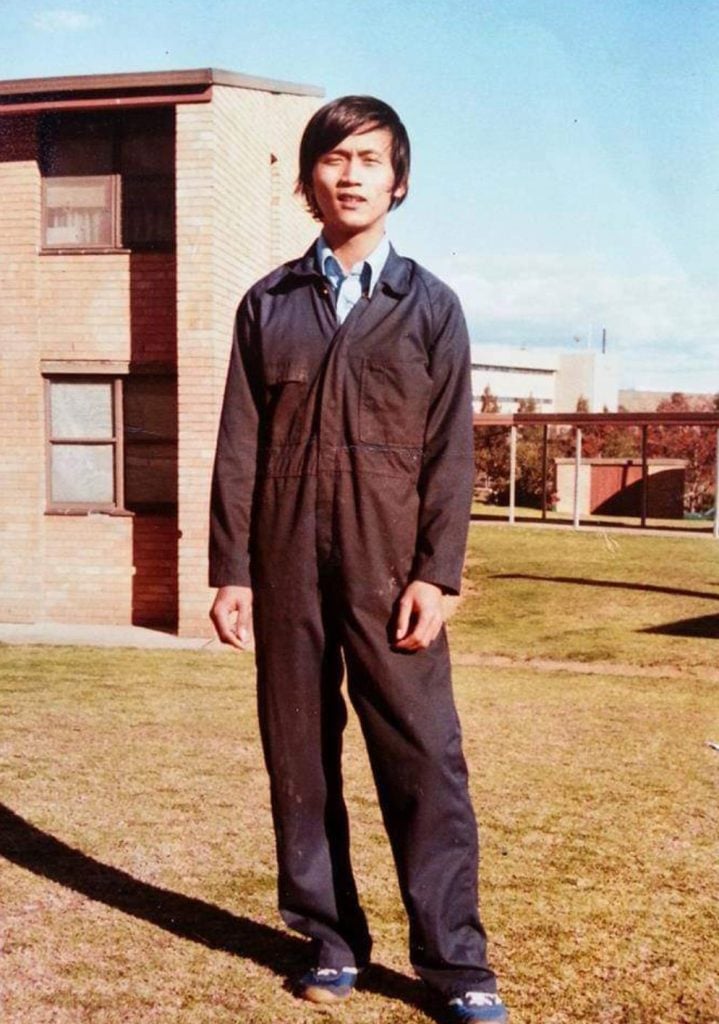

Dr Quangh Phu Ho worked as a spray painter in the 1980s.

Four years later, Quang went with his flatmate to sit for an exam to work at Australia Post. He got the job. It would seem that he had finally made it: after years fleeing, he now had achieved economic stability, a good job with reasonable working hours and, most importantly, he and his family were safe. But he was not happy. He says, “I was bored.”

Quang purposely made a mistake at work, hoping to get fired. When the time came, he walked into his boss’ office, looking forward to an angry reprimand. He encountered something completely different.

“My boss said ‘I think you’re the same age as my son. You remind me of him.’ He took me completely off-guard. This warm assessment was not what I was expecting. He asked me why I had done what I had done, and I felt compelled to tell him the truth. That I was bored. So he asked me what I wanted to do, and when I said I would like to go back to study, he offered to help me pay for my studies if I stayed. I was completely taken aback.”

Over the next years, Quang studied at TAFE full-time during the day and worked full-time at night. He finished a Higher School Certificate and, at 28 years of age, enrolled in UNSW to study medicine. Then, he spent further nine years in training to become an obstetrician and gynaecologist, specialising in infertility.

“My mother had nine children. I remember seeing her bedridden, suffering from complicated pregnancies, but somehow, she always found time to care for others. She taught me that the meaning of life is to help people. So, if I can help other women not to suffer as my mother did, I am happy.”

For the last 20 years, Quang has delivered up to five babies and consulted with up to 50 patients per week at his surgery and at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. He also works at an IVF clinic, has been a senior lecturer at South Western Sydney Clinical School since 2014, and teaches medical students and doctors from Vietnam to improve healthcare for people living in poverty.

Dr Quang Phu Ho with his colleagues.

“I love teaching students and seeing how they learn. Lately it’s becoming harder because I do not have a PhD and universities are asking for more and more publications and qualifications. But I hope in the future I can get more opportunities to share my knowledge. Who knows? After all, my life has been full of surprises. Life has taught me that even if you are good at something, you have to try harder. If I can help people in their lives, I am happy to do my work.”

Quang has been a recipient to numerous awards, including the UNSW Dean of Medicine Faculty’s award for Best Teaching, the UNSW Alumni Award for Innovation, Leadership and Community Services, and the South Western Sydney Clinical Dean award for contribution in teaching. Early in June 2019, he was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for his service in obstetrics and gynaecology.