‘When I walked out of the birth suite, I felt like my feet weren’t touching the ground.’

Mark Beaves, an 18 year old nurse-trainee, had just witnessed his first childbirth. ‘The whole thing was completely miraculous to me. It was beautiful, gentle and just…idyllic. It never really left me.’

Captivated by his experience, Mark decided to become a midwife in 1998. However, his fervent passion would take him much farther. Today, Mark has 40 years’ experience in clinical nursing and midwifery, 17 years in performing ultrasound and caring for women with high-risk pregnancies and 15 years as Manager of RANZCOG’s Fetal Surveillance Education Program.

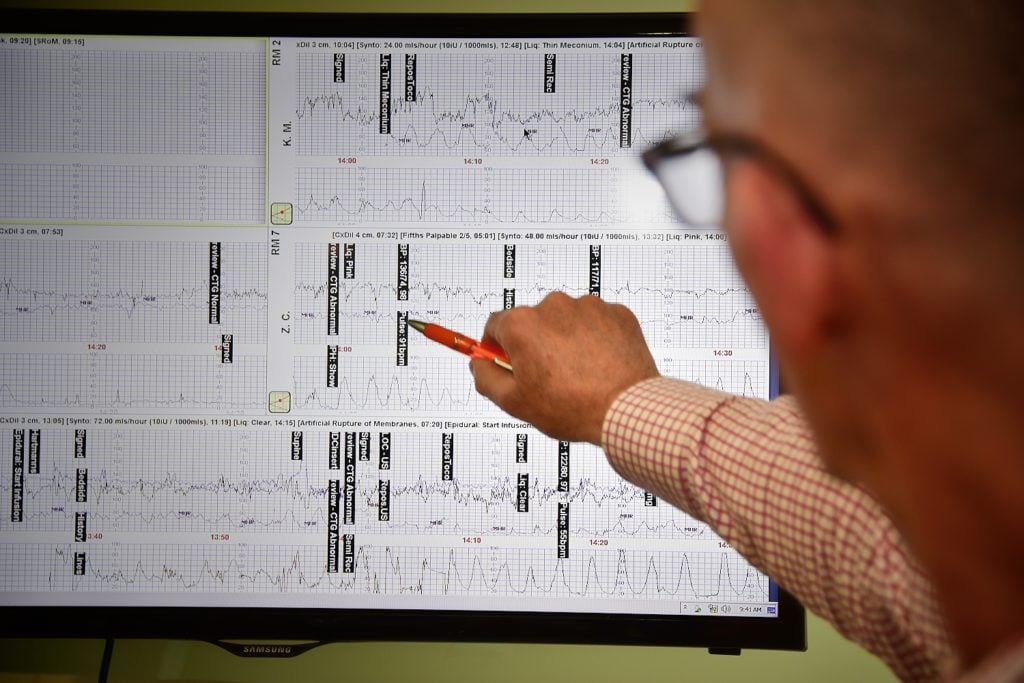

Mark Beaves, FSEP Program Manager, focuses on a CTG display.

Breaking paradigms

‘I remember thinking I wanted to travel and that nursing was something I was interested in that would also allow me to do so. I started my nursing training when I was 17. But for a guy to do midwifery in the 1970s…that was a completely different story.’

Nursing itself has always been a gender-disparate profession. Back in 1986, 92.6% of all nurses were female; a figure that has not changed much throughout the years. In 2017, 89.1% of all Australian nurses were female and 10.9%, male. For midwifery, the disproportion increases. According to data from the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, in 2017 only 1.71% of nurses and midwives were men. There is no gender-related data available for the 1980s.

As Mark explains, ‘In the 1980s the catch-cry for midwives was “for-women by women” which leaves the male midwives (and husbands for that matter) a little bit on the outside.’ Mark finished his training as a nurse and went into coronary care, then intensive care training. In 1998 the call of a cherished memory and an unpursued dream meant that he enrolled in a midwifery course at Monash Health, Clayton.

I had very few difficulties being a male midwife. For the most part, when women realised I was serious about it, that it’s what I wanted to do and that I was going to look after them, support them, keep them safe, it didn’t matter if I was male or female.’

Mark worked at Monash Health as a rotating midwife for a few years before being employed in the birth suite and then, ultimately, in the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Department. This area specialises in fetal surveillance, assessing fetal wellbeing by gaging the fetal heart rate and observing the fetus under ultrasound. ‘I just realised that everything that I’d done to this point came together in fetal monitoring. I banged on their door until they let me go there and work.’

Embedding change

In 2000 the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (VMIA) commissioned an expert review of nearly 400 cases of obstetric medico-legal claims in Victoria arising between 1993 and 1998 that identified inadequate use of intrapartum fetal surveillance as a major contributor to poor outcomes in childbirth and, hence, the claims burden. In order to address this, VMIA funded RANZCOG to develop an evidence-based clinical guideline on intrapartum fetal surveillance. The objective was for this guideline to facilitate standardisation of existing local education programs to reduce the number of babies damaged in labour. However, RANZCOG recognised that the development of guideline alone, unsupported by education, was unlikely to have significant impact on clinical practice. They made their point. In 2003, the Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance Education and Credentialing (IFSE&C) Pilot Project was funded by VMIA and the Department of Human Services Victoria (DHS) to assess the feasibility and acceptance of a state-wide education program. RANZCOG put up a job advertisement for a clinical program lead. ‘When I read the job description I remember thinking: the only thing that’s missing on this is my name at the top’, says Mark.

Initially, Mark started on his own in a small office within RANZCOG’s premises. The first thing that he did (along with Professor Euan Wallace and Valerie Jenkins) was to undertake a formalised survey of senior medical and midwifery staff in all Victorian hospitals in order to map current education and assessment practices in fetal surveillance. The survey returned surprising results: Out of 58 hospitals, only 19 had an existing education program in fetal surveillance, and only six of these had any competency assessment. Based on this information, the team then proceeded to design and carry out the IFSE&C Pilot Project with ten Victorian public hospitals in 2004. In 2005, when the project was evaluated, it was deemed a success, renamed the Fetal Surveillance Education Program (FSEP) and implemented on a state-wide scale.

The program grew exponentially. In 2004, 2005 and 2006 there were 419, 1839 and 2181 participants respectively. By 2005, FSEP educated over 80% of Victoria’s public and private hospitals. In the following years, the program became cost-neutral, the educational material was refined and the program structure streamlined. Demand was such that interstate and international sessions were added to the plan. By 2016, a large population-based study showed a 51% reduction in intrapartum fetal death attributed to hypoxia after the implementation of FSEP. Currently the program has 12 clinical educators, all of who are midwives, delivering more than 300 lectures to 150 sites and over 8000 clinicians per year.

With a passion for sharing knowledge to improve outcomes, Mark travels extensively to deliver FSEP training programs.

Igniting conversations

Today, FSEP continues to grow throughout Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands. However, the program hasn’t yet permeated evenly across all national territories. ‘I’d really like to see that. If we can make sure that everyone is taking this program on a regular basis, outcomes should improve.’ There’s something else, however, that has surprised Mark. ‘There is something I hadn’t thought about that we constantly get positive feedback on: the improvement in communication between clinicians.’

Mark states that until recently, the use of terminology around Fetal Surveillance differed from hospital to hospital and even within birth units. Therefore, cardiotocography discussions often took place separately between doctors and midwives. Since without standardised terminology there cannot be standardised management, FSEP gains heightened importance as a multidisciplinary standardisation tool that finds common ground in a shared goal.

‘In the end, our (FSEP) mandate is to improve outcomes. Every day, when I wake up, that’s what I’m thinking about: “how can we make it a little bit better?” It makes getting up really easy; especially when we have such a passionate team pushing in the same direction. Hopefully midwives and medical teams can continue to work together this way. It can’t be an “us and them” when ultimately, we share the same goal.’