The performance of surgical operations is recognised as the most complex psychomotor activity that a human can perform.1 The overall aim of surgical training is to provide society with a knowledgeable, skilled and up-to-date cohort of professionals who strive to maintain and develop their expertise over the course of a lifelong career. In short, the goal is to train surgeons who create the best possible outcomes for patients while simultaneously minimising deaths, complications and poor functional results.

Despite this aim, published surveys indicate that the majority of new RANZCOG Fellows are not confident, nor feel competent, to undertake independent surgical practice.2 This is sadly not a problem that only exists within obstetrics and gynaecology in Australia – it is well recognised worldwide and within many surgical specialties.

It has been recognised by RANZCOG that a standard Fellowship qualification can no longer signify that recipient can do ‘everything’3 and the latest curriculum review with the introduction of advanced training modules (ATM) was designed to improve surgical access and training for surgically inclined trainees. But the question remains – is FRANZCOG training suitable for a surgical specialty; can it train gynaecologic surgeons?

Development of expertise

Gynaecologic surgery consists of a broad range of surgical techniques, encompassing vaginal, open and laparoscopic surgery. Traditionally, training in gynaecologic surgery was based on an apprenticeship model, where large volumes of cases were experienced with various levels of involvement, to obtain expertise. Ericsson4 famously argued that mastering a skill requires 10 000 hours (or 20 hours a week for ten years) of deliberate practice. Multiple changes in training, including increasing trainee numbers and advances in the medical and interventional management of gynaecologic conditions rather than surgical management, has resulted in decreased surgical patients.5 Regrettably, it would be very difficult to imagine any of our general O&G trainee workforce getting 20 hours of operative practice or preparation time per week to gain this expertise.

This is significant, as it has been clearly demonstrated that the level of a gynaecologic surgeon’s training influences their surgical skill and expertise. A retrospective review of 2000 cases in a single site demonstrated that surgeons who had undergone additional training to the standard FRANZCOG had shorter operating length of time and decreased complication rates.6 Additionally, while the surgeon’s level of experience did not influence the complication rate, the current case volume was the most significant predictor of lower complications. I would hypothesise that this is itself sufficient evidence that FRANZOG training simply isn’t adequate for surgical training.

The issues with FRANZCOG training

At six years in length, FRANZCOG training is comparable to other surgical specialties, but is unique in that it truly is a dual training program with that time divided between both obstetrics and gynaecology. While there are surgical opportunities in both, it does also mean double the non-technical or non-surgical requirements. It is also well documented that obstetric service forms a predominant part of trainees’ work, which further exacerbates the problem.7 Most trainees feel that that while the hours they worked were adequate to achieve their non-technical skill, they did not feel confident in achieving their technical skill requirements.8

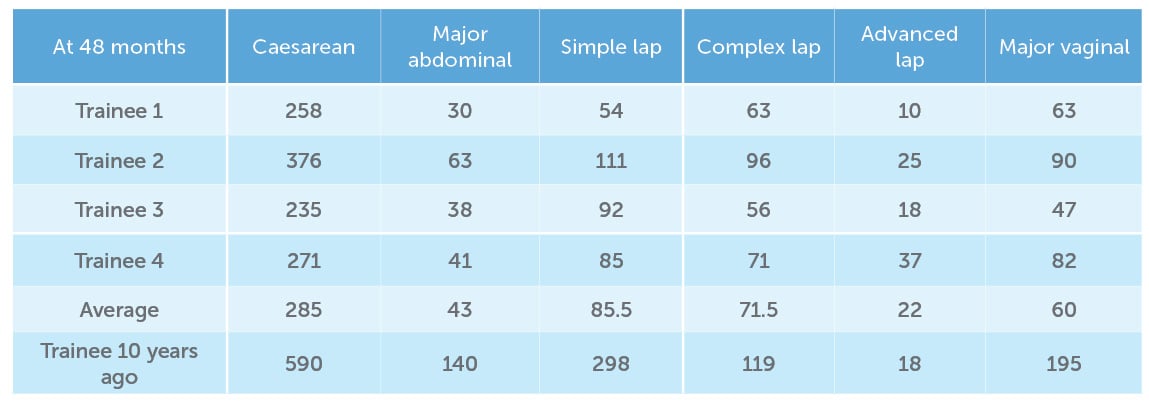

The decrease in surgical caseload is well documented and is the most significant issue faced by FRANZCOG training.9 In an average general rotation, a trainee could expect to find themselves in the operating theatre for four hours per week and these cases will be shared between the consultant, the senior registrar, the registrar and resident. This is far below the required hours to achieve expertise for the trainee, or to adequately maintain the consultant’s surgical skill and surgical volume. The actual operating time in each rotation will also vary, as will the actual rotations experienced by each trainee, leading to discrepancies in surgical exposure and experience within each cohort. Table 1 exhibits the variation in surgical exposure for a cohort of Year 4 trainees from Western Australia. It also compares the numbers from a trainee from 10 years ago, demonstrating the substantial overall decrease in exposure. The decrease in surgical numbers is further exacerbated by the fact that 60 per cent of surgical procedures are now performed within private hospitals and there is little integration of RANZCOG training into the private sector.10

Another significant issue within FRANZCOG training is the quality of teaching available for trainees. There is no formalised education toward teaching during FRANZCOG training. Obermair2 showed that between 20 and 25 per cent of respondents rated their consultants’ teaching ability as ‘poor’. The reasons for this are probably twofold. Firstly, two thirds of RANZCOG graduates find work within the public system, meaning these same undertrained and unconfident new consultants are expected to train trainees themselves.11 The second reason is that the number of senior consultants available for teaching is decreasing, with a large percentage of older Fellows retiring, further reducing the available teachers for the trainee.12

RANZCOG has changed advanced training to incorporate ATMs with an aim to improve access to surgical training; however, this has not addressed the true operative case shortage. The vast majority of trainees will be required to complete the Gynaecology Generalist Module, yet published data from RANZCOG have shown that a significant number of sites do not meet the minimum surgical case number criteria required.13 While we set target standards to be met from a case volume point of view, the trainee that does not complete the adequate number of procedures is not penalised, which is repeatedly stated in the curriculum. In addition, the purported surgical numbers have been boosted recently with the allowance of ‘double counting’ where more than one trainee can claim a procedure. While this method allows senior trainees who are supervising their juniors to still gain logbook experience, the reports of numerous trainees claiming the single procedure may reflect an inadequate caseload and procedures being counted where minimal input has been made.

The learning curve for hysterectomy has been well documented, with the number of cases required to achieve proficiency ranging from 20–30 for vaginal hysterectomy and between 30–145 for laparoscopic hysterectomy.14 Despite this, the required number of hysterectomies to complete the Advanced Generalist Gynaecology ATM is five cases, combining abdominal, laparoscopic and vaginal. While there is an expectation that trainees will complete other modules during their advanced training, there is no penalty for not doing so. This is clear evidence that most trainees completing their generalist training program will have failed to achieve surgical proficiency.

Table 1. Operative numbers of trainees from Western Australia at four years completed training.

How does it compare?

Having completed both a FRANZCOG and a surgical fellowship, I feel a comparison is a suitable way of judging FRANZCOG training’s suitability. The Australasian Gynaecological Endoscopy and Surgery Society (AGES) Fellowship is a two-year program aimed at producing laparoscopic surgeons. Sites must apply to AGES for a two-year accreditation, proving their caseload and other minimal criteria and accreditation will be removed if they have failed to maintain the requirements. Each site must have a minimum of two approved supervisors and they are offered surgical teaching training by AGES through the Train The Trainer Workshops. A trainee must complete a minimum of 110 laparoscopic procedures during their fellowship, which is nearly six times higher than what is expected in the generalist ATM. Finally, private hospital operating is integrated into their timetables and trainees spend on average one day per week as the primary operator and a similar amount of time as a first assistant. This use of the private sector optimises the first operator experience of the trainee on the cases that are then theirs. Similar training models exist in the surgical subspecialties of gynaecological oncology and urogynaecology.

Who are we training?

The final question to be answered is whether there really is a role for a ‘generalist’. Surgical outcomes improve with surgeon volume and there is a growing belief that every woman deserves a high-volume gynaecologic surgeon.15 American data suggest that 80 per cent of gynaecologists are low volume and that the average gynaecologist performs 8.5 hysterectomies per year.16 A large meta-analysis published by two FRANZCOG-trained gynaecologists showed that gynaecologists performing procedures once a month or less were found to have higher rates of adverse outcomes.17 It was demonstrated that low-volume surgeons had a 30 per cent increase in the risk of experiencing any in-hospital complication, a 60 per cent increase in the risk of incurring an intraoperative complication and a 40 per cent increase in the risk of incurring an in-hospital postoperative complication. With this in mind, we must ask who should be doing the surgery, if our aim is to have the best outcomes for outpatients.

Conclusion

Gynaecologic surgery has been caught up in a perfect storm with increasing numbers of trainees competing for an ever-decreasing caseload. The absence of adequate training targets and the lack of enforcement of the low existing targets are sinking the surgical ship. The spiral downwards is worsening as the training program outputs consultants who then become new trainers themselves, still trying to learn the basics. Most generalists will not perform enough cases per year to maintain their surgical skills and decrease their adverse outcomes.

In its current status, the FRANZCOG training program is not adequate for training a surgical specialist. Perhaps it is time to face the truth – not everyone can be a gynaecologic surgeon and not everyone should.

References

- RH Bell. Why Johnny cannot operate. Surgery. 2009;146(4):533-42.

- A Obermair, A Tang, D Charters, et al. Survey of surgical skills of RANZCOG trainees. ANZJOG. 2009;49(1):84-92.

- R Sherwood. Controversies in training. O&G Magazine. Vol 16, No 4. Summer 2014.

- KA Ericsson. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Academic Medicine. 2004;79(10):S70-81.

- M Permezel. How can safe working hours produce a safe specialist obstetrician & gynaecologist? ANZJOG. 2017;57(5):491-2.

- RM McDonnell, JL Hollingworth, P Chivers, et al. Advanced training of gynecologic surgeons and incidence of intraoperative complications after total laparoscopic hysterectomy: a retrospective study of more than 2000 cases at a single institution. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(5):810-5.

- R Sherwood. Controversies in training. O&G Magazine. Vol 16, No 4. Summer 2014.

- PE Tucker, PA Cohen, MK Bulsara, J Acton. Fatigue and training of obstetrics and gynaecology trainees in Australia and New Zealand. ANZJOG. 2017;57(5):502-7.

- PE Tucker, PA Cohen, MK Bulsara, J Acton. Fatigue and training of obstetrics and gynaecology trainees in Australia and New Zealand. ANZJOG. 2017;57(5):502-7.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Future Health Workforce – Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Department of Health, Australian Government. 2018. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/85A235008D12097BCA2582FD00793F4D/$File/AFHW_%20OG_Report_FINAL.pdf.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Future Health Workforce – Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Department of Health, Australian Government. 2018. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/85A235008D12097BCA2582FD00793F4D/$File/AFHW_%20OG_Report_FINAL.pdf.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Future Health Workforce – Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Department of Health, Australian Government. 2018. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/85A235008D12097BCA2582FD00793F4D/$File/AFHW_%20OG_Report_FINAL.pdf.

- M Permezel. The Australian perspective of the modern gynaecologist: Surgical training in 2016. Lecture presented at AGES XXVI Annual Scientific Meeting; 2016 Brisbane.

- JN Acton. Surgical training: the past, present and the future. Digital Poster presented at AGES XXIV ASM. March 2014. Sydney.

- A Walter. Every woman deserves a high-volume gynecologic surgeon. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):139-e1.

- E Mikhail, L Scott, B Miladinovic, et al. Association between fellowship training, surgical volume, and laparoscopic suturing techniques among members of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. Minim Invasive Surg. 2016;2016:5459147.

- A Mowat, C Maher, E Ballard. Surgical outcomes for low-volume vs high-volume surgeons in gynecology surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):21-33.

Leave a Reply