Each day in Australia on PANDA’s National Perinatal Anxiety & Depression Helpline, we talk to expecting and new parents affected by perinatal mental illness. While every story is different, there are many common themes, including parents not expecting that this would happen to them, not recognising that they are sick, or knowing something is wrong but avoiding seeking help due to concerns they will be perceived as a bad parent.

As well as providing critical support to callers, PANDA strives to raise awareness of this common and serious illness so that families can recognise what is happening and get help as soon as possible. Our more than 300 Community Champions are at the heart of this work. Megan, one of our Champions from Western Australia, has allowed us to share some of her story:

I now realise I was incredibly anxious from about 22 weeks. When I developed pre-eclampsia and was stuck in hospital, people kept telling me that it would be okay; however, after a difficult birth resulting in my baby needing to be resuscitated and then taken to the NICU, I felt like the rug had been pulled out from under me. I found out a few hours after her birth she was missing fingers and had other birth defects and health concerns that no one could explain to me and although I didn’t realise it at the time, my anxiety was rapidly increasing.

I was constantly worried something was going to happen to my daughter, she was not well, and I wanted to do everything in my power to protect her. I would be with her 24/7, it was rare that anyone else even held her. She screamed constantly, I didn’t trust anyone else would or could give her the care she needed. I knew my anxiety wasn’t healthy at this stage and started dropping hints at appointments with doctors that I was anxious.

I went to my GP to ask to see a psychologist, she asked me a few questions, did an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, which I always lied on, told me we had a great connection, that it was no wonder I was a little anxious because of her health concerns, that I needed some sleep and told me I didn’t need a referral and sent me on my way.

Megan, a PANDA Community Champion, with her daughter and son.

Perinatal mental illness

Although Australia is acknowledged as a world leader in perinatal mental health, a significant number of Australian parents are not identified as at risk of, or experiencing, perinatal mental illness, and factors such as stigma and shame prevent many from seeking help. With early identification and access to appropriate care, it is possible to reduce the severity of illness, minimise the need for specialist perinatal mental healthcare, and improve health outcomes for the entire family unit.

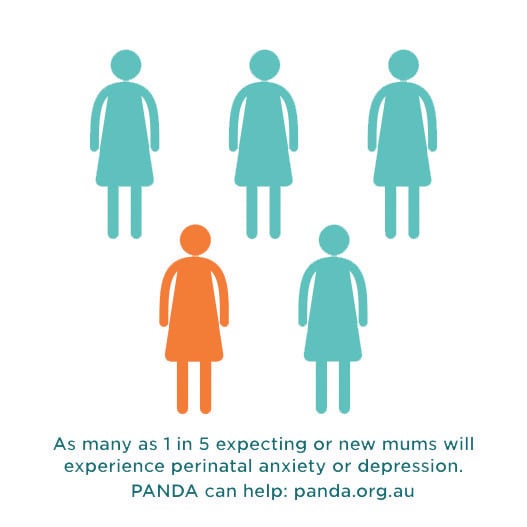

Specific estimates of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal mental illness vary due to methodological and population differences between studies. There is, however, wide agreement that mental illness in the perinatal period is common and of critical importance, with up to one-in-five expecting or new mothers experiencing anxiety and/or depression.1

For every 1000 women who give birth, it is estimated that 1–2 will experience postnatal psychosis.2 Although less common than anxiety and depression, psychosis often presents in the early weeks following birth with acute onset and rapid deterioration, with most women requiring admission to an inpatient mental health facility.

Risk factors

The perinatal period can be a period of vulnerability for women’s mental health, although some women are more likely to experience perinatal mental illness than others. Key risk factors include a lack of partner support; inadequate social support;3 4 history of abuse or domestic violence;5 6 a personal history of mental illness;7 8 low self-esteem; and, as was the case for Megan, past or current pregnancy complications.9 10

Although not all of these factors are modifiable, early identification of risk factors presents opportunities to put additional supports in place to help protect the woman’s, and her family’s, mental health during pregnancy and the early years of their child’s life.

Seeking help

As Megan’s story demonstrates, a range of factors can act as barriers to parents seeking help, including stigma; worry about being perceived as unable to cope; lack of knowledge about available services and how to access them;11 discrimination;12 and practical limitations, including financial and transportation difficulties, and language barriers.13 Community awareness regarding perinatal mental illness remains poor, particularly regarding anxiety and mental health challenges experienced by men.14

Resources to support your practice

Megan’s story illustrates the reality that many parents will not openly tell their care providers how they are really feeling. Undertaking a thorough psychosocial health assessment early in pregnancy and regularly enquiring about psychosocial health throughout the perinatal period can help to ensure every parent receives the care and support they need.

In addition to the Helpline, PANDA provides a number of resources that can help you support the mental health of the women and families you care for:

Mental Health Checklist for Expecting and New Parents

You might like to point parents to this handy checklist available at panda.org.au. It provides a quick, anonymous, accessible way for expecting

and new parents and carers to explore their emotional wellbeing, identify potential symptoms of perinatal mental illness, and seek help. The checklist includes 30 tick-box, plain language questions covering a wide range of symptoms and associated risk areas. Users can access a printable PDF summary of their responses at the completion of the checklist, which they can use to start conversations with their care providers.

Consumer approved resources

- PANDA’s website provides consumer friendly information, including stories of recovery shared by our Community Champions

- Our second website, howisdadgoing.org.au, has been specifically developed for expecting and new dads

- PANDA, in collaboration with our Australia-wide network of lived experience volunteers, has established a suite of consumer and health professional resources that can be viewed and ordered at panda.org.au

A final word from Megan

Obstetricians and gynaecologists can play a key role in enabling parents to discuss how they’re really feeling, which can be an important first step in the recovery process. As Megan explains: I found speaking openly and honestly about how I felt and what I was experiencing was empowering and the turning point for me.

PANDA’s National Helpline

In 2010, PANDA was funded by the Australian Government to provide the National Perinatal Anxiety & Depression Helpline, supporting families and health professionals Australia wide. The Helpline manages approximately 12 000 calls each year.

PANDA’s Helpline works with callers across the spectrum of perinatal mental illness: difficulties with transition to parenthood, mild to moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, and other mental health issues. The Helpline is staffed by a skilled team of professional counselling staff, and a peer support (volunteer) program is offered for callers experiencing mild anxiety or depression. The first time a parent calls the Helpline a full biopsychosocial and risk assessment is completed, with ongoing support calls provided to assist callers while they make vital connections to services local to them.

The Helpline is free and available Monday–Friday 9am–7.30pm AEST/AEDT on 1300 726 306.

References

- MP Austin, N Highet, The Expert Working Group. Effective Mental Health Care in the Perinatal Period: Australian Clinical Practice Guideline. Melbourne; 2017.

- I Jones, PS Chandra, P Dazzan, LM Howard. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Lancet. 2014;384:1789-99.

- A Biaggi, S Conroy, S Pawlby, CM Pariante. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62-77.

- CA Lancaster, KJ Gold, HA Flynn, et al. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5-14.

- A Biaggi, S Conroy, S Pawlby, CM Pariante. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62-77.

- LM Howard, S Oram, H Galley, et al. Domestic Violence and Perinatal Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):1-15.

- A Biaggi, S Conroy, S Pawlby, CM Pariante. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62-77.

- K Falah-Hassani, R Shiri, CL Dennis. The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal co-morbid anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2017;47(12):2041-53.

- A Biaggi, S Conroy, S Pawlby, CM Pariante. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62-77.

- MW O’Hara, JE McCabe. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:379-407.

- CL Dennis, L Chung-Lee. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323-31.

- JM O’Mahony, TT Donnelly. How does gender influence immigrant and refugee women’s postpartum depression help-seeking experiences? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;20:714-25.

- JM O’Mahony, TT Donnelly. Immigrant and refugee women’s post-partum depression help-seeking experiences and access to care: A review and analysis of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17:917-28.

- T Smith, AW Gemmill, J Milgrom. Perinatal anxiety and depression: Awareness and attitudes in Australia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2019;1-10.

Leave a Reply