Caesarean section is one of the most commonly performed surgeries and rates are continuing to increase all over the world. Well-known complications of a caesarean section scar include placenta acreta, placenta praevia, scar ectopic, and scar dehiscence (either antenatally or intrapartum). However, we are less familiar with the implications from a caesarean scar defect, such as dysfunctional uterine bleeding, pelvic pain and secondary infertility.

History

Isthmocele, also known as caesarean scar defect, uterine scar deficiency, uterine niche or pouch, was first described by the obstetrician gynaecologist Morris in 1995.1 This entity is only just being identified and described in the literature, and is becoming a subject of attention, especially in those who present with secondary infertility. The reported incidence of isthmocele ranges from 24–84 per cent.2 3 With the incidence of caesarean section increasing, it is important that we are aware that isthmocele could be a cause of these symptoms.

Presentation

Isthmocele may present with secondary infertility, menstrual disturbance (typically postmenstrual spotting), continuous brown discharge, dysmenorrhoea, pelvic pain, and/or dyspareunia.4 5 6 Isthmocele can also be asymptomatic. The intensity of symptoms is thought to be related to the size of the isthmocele.7 As other pathology may present with these symptoms, there is often a delay in diagnosis.8

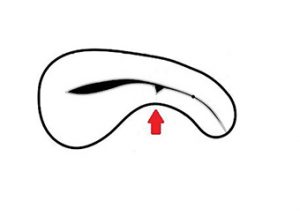

Figure 1. MRI showing isthmocele and pictorial diagram.

Definition and diagnosis

There is no international standardised definition or diagnosis for isthmocele. It can be identified on imaging with transvaginal ultrasound scan (TVUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or at the time of hysteroscopy. Isthmocele or caesarean scar defect has been defined as ‘any visible filling defect in the anterior isthmus of the uterus on transvaginal ultrasound scan’.9 A ‘larger’ isthmocele is thought to be when the remaining myometrial thickness is less than 2.5–3.0 mm.10

Prevalence

Studies have found wide prevalence ranges. Bij de Vaate et al estimated the incidence to between 24–84 per cent, Wang et al reported 6.6–69 per cent.11 While Florio, Tower and Frishman reported and incidence of 30–52 per cent and 19.4–88 per cent respectively.12Although isthmocele is quite prevalent, it is not always associated with secondary infertility.

One of the largest systematic reviews on caesarean section scar-associated secondary infertility showed a correlation between caesarean delivery and increased odds of subfertility when compared to vaginal delivery (1.6 95% CI 1.45-1.76, p<0.00001).13

There is growing evidence that IVF success rates are lower in patients who deliver via caesarean section when using embryos from the same cohort,14 suggesting a possible impact of embryo implantation.

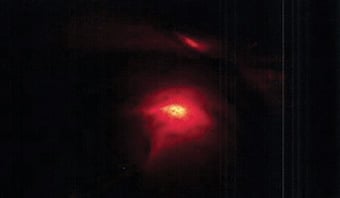

Figure 2. Isthmocele seen at laparoscopy.

Risk factors

A number of risk factors are thought to be implicated in the development of isthmocele. The list includes more than one caesarean section, retroflexed uterus, pre-eclampsia, maternal age less than 30 years, duration of labour more than five hours, cervical dilation more than 5 cm at time of delivery, lower station at delivery (below pelvic inlet), incision in the cervical area, use of oxytocin, exclusion of endometrial layer during repair, one-layer closure of myometrium, delayed absorbable sutures, and more ischemic closure.15 16

Investigations

TVUS and MRI are considered to be the gold standard when investigating for isthmocele,17 although ultrasound is usually considered as the first diagnostic tool.1 The depth and length of the defect are measured along with the remaining myometrial wall thickness. Other key sonographic findings to consider are inward and outward protruding of the scar, scar retraction and haematoma.18 On TVUS, the defect is seen as a triangular hypoechogenic zone in the uterine scar area; the term for this is ‘niche’.19Saline infusion sonohysterography and hysterosalpingography have also been used to detect isthmocele.

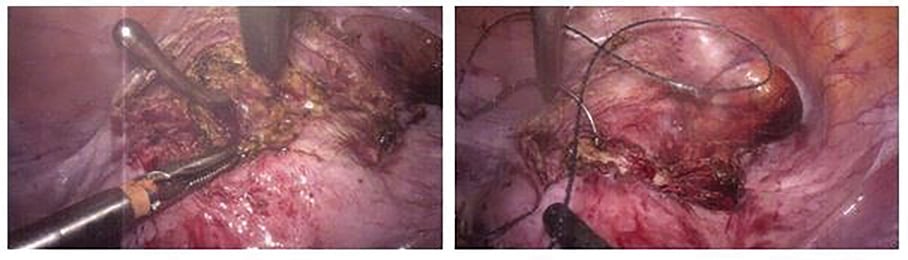

Figure 3. The defect can be seen under the light of the hysteroscope, ‘Halloween sign’.

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism of how isthmocele or caesarean scar defect occurs is not completely understood.20 It is possible that two mechanisms are at play; inadequate healing of the caesarean section scar and the resulting thickness of the myometrium.21 Reduced scar contractility and abnormal myocontraction, along with the presence of functional endometrium leads to the accumulation and impaired drainage of menstrual blood in the cavity.22 23 This results in intermenstrual bleeding and pelvic pain.24

The retained menstrual fluid is likely to impair the quality of cervical mucous, sperm viability and disrupt sperm swim-up. Bleeding may cause the blastocyst to be washed out of the uterus, interfering with embryo implantation.25 26

In addition, endometrial abnormalities around the scar defect, such as overhanging endometrium and/or inclusion of endometrium within the scar, could lead to abnormal bleeding. Careful re-approximation of the endometrial layer during uterine closure could reduce endometrial abnormalities and dysfunctional bleeding.27

Treatment

Treatment should be offered to symptomatic women. There is no ‘gold standard’ or treatment protocol for isthmocele repair, and no technique that has shown a statistically superior outcome.28

Although some report medical therapy can help to improve symptoms by suppressing menstruation,29 others would argue that medical treatment with the combined oral contraceptive pill or Mirena shows no benefit.30 Hormonal treatment is also not suitable for patients who are planning a pregnancy.

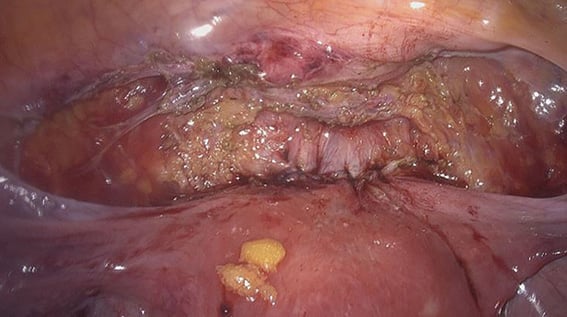

Both hysteroscopic and laparoscopic resection and repair of isthmocele have high success rates of treating both infertility and bleeding disturbance, and a variety of different surgical approaches have been described.31

Isthmocele repair was first performed laparoscopically by Jacobson in 2003.32 The laparoscopic method has the advantage of increasing the thickness of the myometrial layer after repair.33 It is the preferred surgical approach, particularly if the residual myometrium is less than 3 mm thick.34 35 Restoring normal myometrial thickness is important in those patients planning a pregnancy to help reduce the risk of scar rupture.7 Furthermore, the laparoscopic approach has a reduced risk of incomplete removal of scar tissue, uterine perforation and bladder injury, which is associated with hysteroscopic resection.36 37

The crucial step of laparoscopic repair is to correctly identify the uterine scar defect.38 A popular technique described in the literature is the ‘Rendezvous technique’.39 This is a combined technique where the isthmocele is identified at laparoscopy with the simultaneous use of hysteroscopy to outline the defect with its light source. The defect can be seen under the light of the hysteroscope and is known as the ‘Halloween sign’40(See Figure 3). A Foley catheter or TVUS can also be used during laparoscopy to help identify the location of the isthmocele.41 42 It is unclear which type of energy source or suture material is best to repair the scar defect.43

Symptoms are generally improved after repair of isthmocele, with one study reporting a 97 per cent improvement in pain.44

Figure 4. Intra-operative laparoscopic excision and repair of isthmocele.

Future pregnancy

Secondary infertility is an indication for treatment, and the reported pregnancy rates after endoscopic repair of isthmocele are 44–92 per cent.45 46 As with caesarean section, the risk following treatment of isthmocele is scar dehiscence in subsequent pregnancies. The current recommendation is to wait at least three months after repair to get pregnant. It is also recommended that delivery is by caesarean section at term, although successful vaginal deliveries after surgical repair of isthmocele have been reported in the literature.47

There is only limited data regarding isthmocele and pregnancy complications, including uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies. However, what has been observed is the relationship between the size of the isthmocele and the risk of scar rupture, where the larger the defect the greater the risk of scar rupture. Lower uterine thickness near term could also be predictive of uterine rupture.48

Future trends

Isthmocele is common following caesarean section and is associated with infertility. We need a prospective multicentre database to develop an understanding of this condition with regards to diagnosis, surgical techniques and outcomes of surgery so that we can give robust information to our patients.

Figure 5. After laparoscopic excision and repair of isthmocele.

Conclusions

Isthmocele must be considered in patients with a history of caesarean section that present with secondary infertility, abnormal bleeding or pelvic pain. With caesarean section rates rising globally, it is predicted that we will encounter this issue with increasing frequency. By increasing awareness of this common complication, we can help to prevent a delay in diagnosis.

There are few modifiable risk factors in preventing the development of isthmocele following caesarean section. Attention to surgical technique, in particular, avoiding incision into the cervical area, not performing a one-layer closure and not using delayed absorbable sutures could all be taken into consideration at the time of caesarean section.

One of the first steps in diagnostic workup is TVUS; however, often other imaging modalities are employed. Surgical treatment needs to be considered for symptomatic patients, including those who present with secondary infertility. The laparoscopic approach appears to be gaining popularity as the preferred method for treatment primarily because it aims to restore normal myometrial thickness. However, no technique has actually shown a statically superior outcome.

Patients need to be counselled to wait at least three months after treatment before they try for pregnancy, that it does not eliminate the risk of uterine rupture, and that the recommended mode of delivery is caesarean section at term.

Summary

- Isthmocele, also known as caesarean scar defect, is only just being identified and described in the literature and is becoming a subject of attention especially in those who present with secondary infertility.

- Caesarean section is one of the most commonly performed surgeries, and rates are continuing to increase all over the world.

- Isthmocele is an underdiagnosed cause of infertility.

- Isthmocele may present with secondary infertility, menstrual disturbance, dysmenorrhoea, pelvic pain or dyspareunia. Isthmocele must be considered in patients with a history of caesarean section that present with these symptoms.

- One of the first steps in diagnostic workup is TVUS, although other imaging modalities, such as MRI, are often employed.

- Surgical treatment should be offered to patients who present with secondary infertility.

- Reported pregnancy rates after endoscopic repair of isthmocele are high.

- The laparoscopic approach appears to be gaining popularity as the preferred method for treatment, primarily because it aims to restore normal myometrial thickness. However, no technique has actually shown a statically superior outcome.

- With caesarean section rates rising globally, it is predicted that we will encounter this issue with increasing frequency. Raising awareness of this common complication can help to prevent a delay in diagnosis.

I

References

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- H Masuda, et al. Successful treatment of atypical cesarean scar defect using endoscopic surgery. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015;15:342.

- AJ Bij de Vaate, HA Brolmann, LF van der Voet, et al. Ultrasound evaluation of the cesarean scar: relation between a niche and postmenstrual spotting. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(1):93-9.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- H Masuda, et al. Successful treatment of atypical cesarean scar defect using endoscopic surgery. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015;15:342.

- B Urman, et al. Laparoscopic Repair of Cesarean Scar Defect ‘‘Isthmocele’’. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:857-58.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- AJ Bij de Vaate, LF van der Voet, O Naji, et al. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following Cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43:372-82.

- AM Tower, et al. Cesarean Scar Defects: An Underrecognized Cause of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding and Other Gynecologic Complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:562-72.

- A Setubal, et al. Treatment for Uterine Isthmocele, A Pouchlike Defect at the Site of a Cesarean Section Scar. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:38-46.

- F Istvan, et al. Isthmocele: Successful Surgical Management of an Under-Recognized Iatrogenic Cause of Secondary Infertility. Women’s Health & Gynecology. 2017;3(4):1-5.

- F Istvan, et al. Isthmocele: Successful Surgical Management of an Under-Recognized Iatrogenic Cause of Secondary Infertility. Women’s Health & Gynecology. 2017;3(4):1-5.

- OE Keag, JE Norman, SJ Stock. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002494.

- MK Hayes, et al. Repeat in vitro fertilisation success rates are lower in patients who deliver via caesarean section when using embryos from the same cohort. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3):e48.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- AM Tower, et al. Cesarean Scar Defects: An Underrecognized Cause of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding and Other Gynecologic Complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:562-72.

- A Setubal, et al. Treatment for Uterine Isthmocele, A Pouchlike Defect at the Site of a Cesarean Section Scar. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:38-46.

- AM Tower, et al. Cesarean Scar Defects: An Underrecognized Cause of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding and Other Gynecologic Complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:562-72.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- F Istvan, et al. Isthmocele: Successful Surgical Management of an Under-Recognized Iatrogenic Cause of Secondary Infertility. Women’s Health & Gynecology. 2017;3(4):1-5.

- H Nazik, E Nazik. A new problem arising after the cesarean, cesarean scar defect (isthmocele) a case report. Obstet Gyncol Int J. 2017;7(5):00264.

- H Masuda, et al. Successful treatment of atypical cesarean scar defect using endoscopic surgery. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015;15:342.

- A Murji, K Glass, N Leyland. Isthmocele. Journal of Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35(9):779.

- H Nazik, E Nazik. A new problem arising after the cesarean, cesarean scar defect (isthmocele) a case report. Obstet Gyncol Int J. 2017;7(5):00264.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- H Masuda, et al. Successful treatment of atypical cesarean scar defect using endoscopic surgery. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015;15:342.

- H Masuda, et al. Successful treatment of atypical cesarean scar defect using endoscopic surgery. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015;15:342.

- A Setubal, et al. Treatment for Uterine Isthmocele, A Pouchlike Defect at the Site of a Cesarean Section Scar. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:38-46.

- H Nazik, E Nazik. A new problem arising after the cesarean, cesarean scar defect (isthmocele) a case report. Obstet Gyncol Int J. 2017;7(5):00264.

- X Zhang, et al. Prospective evaluation of five methods used to treat cesarean scar defects. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;134:336-9.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- A Setubal, et al. Treatment for Uterine Isthmocele, A Pouchlike Defect at the Site of a Cesarean Section Scar. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:38-46.

- G Aimi, et al. Laparoscopic repair of a symptomatic post–cesarean section isthmocele: a video case report. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:17-8.

- A Setubal, et al. Treatment for Uterine Isthmocele, A Pouchlike Defect at the Site of a Cesarean Section Scar. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:38-46.

- OE Keag, JE Norman, SJ Stock. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002494.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- A Setubal, et al. Treatment for Uterine Isthmocele, A Pouchlike Defect at the Site of a Cesarean Section Scar. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:38-46.

- A Setubal, et al. Treatment for Uterine Isthmocele, A Pouchlike Defect at the Site of a Cesarean Section Scar. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:38-46.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- H Nazik, E Nazik. A new problem arising after the cesarean, cesarean scar defect (isthmocele) a case report. Obstet Gyncol Int J. 2017;7(5):00264.

- A Akdemir, et al. Determination of Isthmocele Using a Foley Catheter During Laparoscopic Repair of Cesarean Scar Defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:21-2.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- AJ Bij de Vaate, LF van der Voet, O Naji, et al. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following Cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43:372-82.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- O Donnez, P Jadoul, J Squifflet, J Donnez. Laparoscopic repair of wide and deep uterine scar dehiscence after cesarean section. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:974-80.

- G Bakavičiūtė, et al. Laparoscopic repair of the uterine scar defect – successful treatment of secondary infertility: a case report and literature review. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2016;23(4):227-31.

- D Bolla, et al. Laparoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Repair of Uterine Scar Isthmocele Connected With the Extra-Amniotic Space in Early Pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:261-4.

Leave a Reply