A 25-year-old, G8P1, presented with abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding at nine weeks gestation. Gynaecological history was significant for one normal vaginal delivery at term, seven years prior, and six previous dilatation and curettages (D&C): one for incomplete miscarriage, and five surgical termination of pregnancies. She had been treated for chlamydia many years prior, with no history of recent infection or pelvic inflammatory disease.

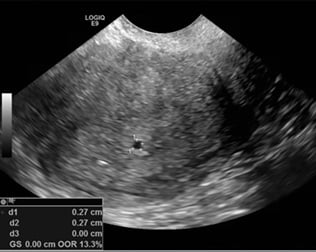

Upon examination, she was haemodynamically stable; abdomen was soft and non-tender with no active bleeding on speculum examination. Pelvic ultrasound showed heterogeneous material within the uterus, suspicious for incomplete miscarriage, a left ovarian cyst measuring 23x17x23 mm and moderate free fluid in the pouch of Douglas. (Figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1. Heterogenous intrauterine material.

Figure 2. Left ovarian cyst and moderate free fluid in pouch of Douglas.

The patient was managed through our outpatient early pregnancy assessment clinic for presumed incomplete miscarriage in the context of inappropriately rising bHCG levels: 4072 to 4652 mIU/mL in 48 hours. She was aware at the time that an ectopic pregnancy was unable to be completely excluded. She opted for D&C after misoprostol for cervical ripening, which was performed two days later. The uterus was confirmed empty on bedside transabdominal ultrasound and she was subsequently discharged from the hospital the same day.

The patient represented to the emergency department day one post-operatively with severe lower abdominal pain. Repeat bHCG showed a rise to 7061 mIU/mL and repeat pelvic ultrasound revealed a left ectopic pregnancy and free fluid in the pelvis. (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Left ectopic pregnancy, CRL 3.02 mm.

She underwent an emergency laparoscopic left salpingectomy for a ruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy with 200 mL haemoperitoneum found on entry. (Figure 4) She recovered well post-operatively and was discharged home the following day with plans for outpatient follow up.

Figure 4. Intraoperative image of left ectopic pregnancy.

Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of both an ectopic and intrauterine pregnancy. Endocervical swabs were negative for chlamydia and gonorrhoea. The patient was subsequently followed up with weekly bHCG levels, until negative, and counselled regarding the risk of recurrence, including the need for early ultrasound in future pregnancies to ensure an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP).

Five months later, the patient presented to the emergency department with a serum bHCG of 1048 mIU/mL at 4+3 weeks gestation by last menstrual period, after missing four days of the combined oral contraceptive pill. She had no pain or bleeding but presented at the advice of her GP. Pelvic ultrasound (Figure 5) revealed a 27x27x27 mm round anechoic focus in the endometrial cavity, possibly an early gestational sac; however, no fetal pole or yolk sac was seen. There was no evidence of ectopic pregnancy and no free fluid in the pouch of Douglas. Plans were made for follow up with repeat bHCG and pelvic ultrasound in one week. The patient did not return for review and while away on holidays she presented to a different facility at 9+6 weeks with severe abdominal pain and a serum bHCG of 3000 mIU/mL. A left ectopic pregnancy in the cornual stump was found and she underwent an emergency laparoscopic removal of the ectopic pregnancy with 1.8 L haemoperitoneum found on entry. Due to plateauing bHCG at level 23–27 mIU/L five weeks post-operatively with an unremarkable pelvic ultrasound, she received a single dose of methotrexate and the bHCG soon returned to negative.

Figure 5. Possible early IUP, 4+6 size, MSD 27 mm.

Discussion

A spontaneous heterotopic pregnancy is defined as multiple gestations arising from a natural cycle located in different implantation sites.1 They are an uncommon occurrence, with incidence reported to be 1 in 30,000; however, with the increasing use of artificial reproductive technology, the total number of heterotopic pregnancies can be expected to rise.2,3,4 The most common site of implantation is an IUP with an ectopic in the fallopian tube, yet implantations in the cervix, abdominal cavity and caesarean scars have also been reported. 5,6

At presentation, women may be unaware of their pregnancy status and typically present with non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain.7 This case illustrates the difficulty diagnosing heterotopic pregnancies with high clinical suspicion required to correctly diagnose these uncommon pregnancies, even after the confirmation of an intrauterine gestation.8 Risk factors for heterotopic pregnancy include, the use of assisted reproductive therapy, previous ectopic pregnancy, prior pelvic surgery or pelvic inflammatory disease.9 Suspicion should be heightened in those presenting with symptoms such as abdominal pain, bleeding, an adnexal mass or haemodynamic instability in the presence of significant risk factors.10,11 Diagnosis can be considered in symptomatic pregnant women ultrasound findings of free fluid in the pelvis or persistently high bHCG levels following termination of an intrauterine gestation.12,13

Ultrasound remains the most reliable and convenient method for diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy, though it can be challenging. The presence of an ovarian cyst on the first ultrasound may have made sonographic identification of an ectopic gestation challenging to the sonographer. For unclear cases with adnexal mass present on initial ultrasound, serial ultrasound is required while the patient remains clinically stable. On progress ultrasound, an ectopic gestation would be expected to increase in size and become visible.14 Despite ultrasound being readily available to most acute medical care providers, more than half of heterotopic pregnancies are diagnosed at the time of surgery. 15

Once diagnosed, options for management include expectant, medical or surgical management with most appropriate choice dependent upon the location of the gestations, size, potential for viability and the haemodynamic status of the patient. 16 Medical management can be delivered either locally or systemically to terminate the pregnancy with localised delivery preferred in the presence of a viable IUP. Surgical options include ultrasound-guided aspiration of products of conception, laparoscopy and laparotomy. 17 Aspiration can only be attempted with a clearly visible gestational sac and often multiple attempts may be required.18 Laparoscopic surgery (salpingectomy or salpingotomy) can be used for removal of the ectopic gestation and is often preferred over laparotomy with reduced recovery time and shorter length of stay. 19 Laparotomy may be preferred in unstable patients with large haemoperitoneum. 20 Literature comparing the different treatment modalities is limited, with no current published meta-analyses.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of an IUP does not exclude an ectopic pregnancy and suspicion should remain high in women with abdominal pain and pelvic free fluid.21 We aim to alert clinicians to the possibility of this diagnosis in order to facilitate early recognition with the possibility for the minimally invasive management to preserve future fertility for these patients.

References

- Chan AJ, Day LB, Vairavanathan R. Tale of 2 pregnancies: Heterotopic pregnancy in a spontaneous cycle. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(7):565-7.

- Chen KH, Chen LR. Rupturing heterotopic pregnancy mimicking acute appendicitis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53(3):401-3.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Ragab A, Mesbah Y, El-Bahlol I, et al. Predictors of ectopic pregnancy in nulliparous women: A case-control study. Middle East Fertility Society Journal. 2016;21(1):27-30.

- Chan AJ, Day LB, Vairavanathan R. Tale of 2 pregnancies: Heterotopic pregnancy in a spontaneous cycle. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(7):565-7.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Ragab A, Mesbah Y, El-Bahlol I, et al. Predictors of ectopic pregnancy in nulliparous women: A case-control study. Middle East Fertility Society Journal. 2016;21(1):27-30.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Chan AJ, Day LB, Vairavanathan R. Tale of 2 pregnancies: Heterotopic pregnancy in a spontaneous cycle. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(7):565-7.

- Esterle J, Schieda J. Hemorrhagic heterotopic pregnancy in a setting of prior tubal ligation and re-anastomosis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2015;9(7):38-46.

- Chen KH, Chen LR. Rupturing heterotopic pregnancy mimicking acute appendicitis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53(3):401-3.

- Esterle J, Schieda J. Hemorrhagic heterotopic pregnancy in a setting of prior tubal ligation and re-anastomosis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2015;9(7):38-46.

- Esterle J, Schieda J. Hemorrhagic heterotopic pregnancy in a setting of prior tubal ligation and re-anastomosis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2015;9(7):38-46.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Esterle J, Schieda J. Hemorrhagic heterotopic pregnancy in a setting of prior tubal ligation and re-anastomosis. J Radiol Case Rep. 2015;9(7):38-46.

- Li JB, Kong LZ, Yang JB, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: Experience From 1 Tertiary Medical Center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2570.

- Chan AJ, Day LB, Vairavanathan R. Tale of 2 pregnancies: Heterotopic pregnancy in a spontaneous cycle. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(7):565-7.

Leave a Reply