The prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasing at an alarming rate worldwide. In Australia, almost half of women of childbearing age are overweight or obese, with rates of 30–50 per cent reported in early pregnancy.1

Excess gestational weight gain and obesity

The most commonly used measure to categorise overweight and obesity is body mass index (BMI). WHO classifies overweight as a BMI of 25 or greater, with further division into pre-obese (BMI 25–29.9kg/m2), obese class I (30 to 34.9kg/m2), class II (35 to 39.9kg/m2) and class III (≥40kg/m2).

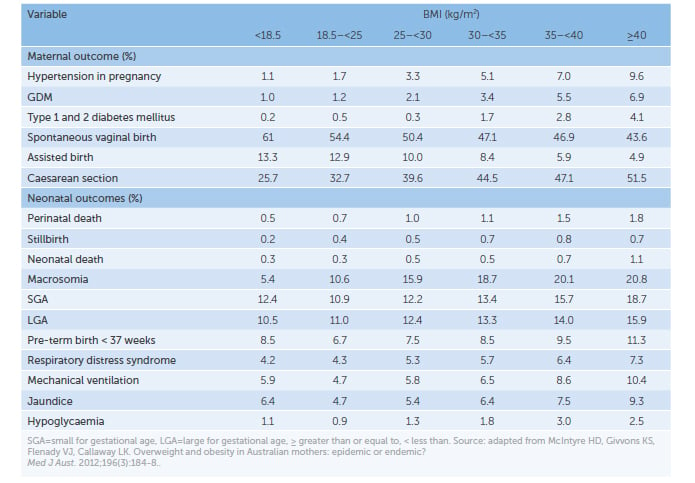

A pre-pregnancy BMI greater than 25kg/m2 affects fertility (subovulation and polycystic ovarian syndrome) and increases the risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, including miscarriage, congenital abnormalities, gestational diabetes (GDM), hypertensive disorders, pre-term delivery, caesarean section and excess fetal growth (see Table 1).2 Similar risks are seen in women with excess gestational weight gain (GWG), independent of their pre-pregnancy BMI.3

Table 1. Association between pregnancy outcomes and BMI.

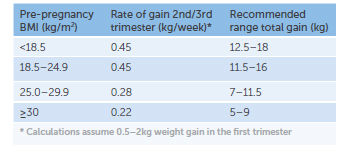

The Institute of Medicine revised (2009)recommendations for weight gain based on pre-pregnancy BMI group (see Table 2).3 Despite these, almost half of pregnant women gain too much weight during pregnancy and a quarter of women do not gain enough.4

Table 2. Institute of Medicine GWG recommendations.

Although excess GWG can occur in all pre-pregnancy BMI groups, it is more prevalent in women who commence pregnancy with a BMI ≥ 25.3 These women are also more likely to have higher weight retention postpartum and risk being overweight or obese in subsequent pregnancies.3

Offspring of mothers, who have a BMI ≥ to 25 (strongest predictor), excess GWG or GDM, have an increased future risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. This raises questions about the effects of intrauterine exposure to overnutrition on fetal programming.5

Weight management

Pregnancy is a time when women may be more receptive and motivated to change behaviours. It is a window of opportunity to introduce weight management strategies. It is also the most likely time for young women to interact with their healthcare providers. However, even in this engaged group, reducing BMI and GWG through lifestyle intervention with diet and exercise is challenging. These interventions reduce the risk of excess GWG, on average, by 20 per cent.6 This potentially means lower rates of maternal hypertension, macrosomia, caesarean section delivery and newborn respiratory distress syndrome.6

An early antenatal visit allows timely referral to a multidisciplinary team, including a dietician. While guidelines on weight management in pregnancy lack clear guidance beyond generic lifestyle modification, a dietician can discuss GWG targets and counsel regarding:

- healthy eating recommendations (variety, portion size, sugar intake)2

- increased activity (20–30 minutes of moderate intensity exercise on most days of the week)2

- regularly tracking weight gain to identify trends2

There is currently no consensus on the level of caloric restriction in pregnancy to prevent excess GWG or avoid weight loss. No guidelines recommend weight loss during pregnancy, due to a greater risk of SGA infants.7

Particularly in women with higher classes of obesity, other multidisciplinary team members may include:

- Obstetric physician

Antenatal assessment and management of obesity-related co-morbidities, such as hypertension, obstructive sleep apnoea, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and renal dysfunction (including proteinuria), may modify pregnancy outcomes. If risk of pre-eclampsia is high, prophylaxis with low-dose aspirin and increased calcium may be warranted.2 - Anaesthetist

Risks are increased in women with obesity for regional and general anaesthesia. Review in the third trimester will allow individualised risk assessment, additional testing, counselling and setting of expectations.2 - Lactation consultant

Breastfeeding initiation and duration are lower in obese women and those with GDM. Furthermore, breastfeeding has been linked to lower risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and obesity, with less postpartum weight retention.8 Specialist support may improve rates. - Physiotherapist/exercise physiologist

Individualised plans for meeting activity goals may assist with compliance. - Psychologist

Women with higher levels of obesity have a greater prevalence of mental health issues. Psychosocial stressors may also predict postpartum weight retention.9

Other considerations in management:

- Additional folic acid (5mg daily, from up to three months preconception until the end of the first trimester), as serum levels are lower than

non-obese women.2 - Assessment of vitamin D, as low levels are more prevalent, and replacement to a normal range may be beneficial.2

First trimester/first antenatal review screening for GDM, due to the higher prevalence and earlier onset of glucose intolerance. If normal, undertake routine screening at 24–28 weeks.2 - Greater frequency of reviews in the third trimester, due to increased risk of hypertensive disorders and abnormal fetal growth. Additional growth scans may be required to address difficulty in clinical assessment.2

- Planning timing, location and mode of delivery. Obese women, particularly in class III, have increased peripartum complications. Assessment of local resources and expertise to determine if safe peripartum care can be delivered, or if transfer of care to a higher level hospital should be considered.2 9

- Postpartum risk management to address: higher chance of PPH (antenatal optimisation of iron stores and greater vigilance after delivery); venous thromboembolism (assessment of risk factor profile, consider prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin).2

Women with obesity are more likely to experience discrimination and prejudice than non-obese women.2 Throughout the pregnancy, appropriate language and an open, non-judgemental manner can help to build a therapeutic relationship, support behavioural change and improve engagement with health professionals.9

Bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery is becoming commonplace in women of childbearing years. In women with higher classes of obesity, it is the most clinically effective treatment to achieve long-term weight loss and reduction in obesity-related complications.10 Surgeries can be restrictive (laparoscopic adjustable gastric band or sleeve), malabsorptive (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, biliopancreatic diversion) or a combination.11

The induced weight loss can increase fertility. Contraception should be discussed concurrently with surgery, to allow for planned conception. Weight loss may also interfere with absorption of oral hormonal contraception and alternate forms should be considered.10

Guidelines suggest delaying conception for 12–24 months post-surgery (particularly in malabsorptive procedures), to optimise maternal weight loss, allow stabilisation of the body’s nutritional state and reduce the potential fetal risk of in utero malnutrition.10 Despite this, limited studies comparing outcomes of women who conceive prior to, and after, the recommended minimum 12-month period do not show significant differences.10

Most pregnancies post-bariatric surgery will have successful outcomes. Small studies have demonstrated a reduced risk of GDM, hypertensive disorders, PPH and macrosomia. However, there is an increased risk of SGA infants and preterm delivery, compared with obese women. To date, no impact on neonatal mortality has been shown.2

Further considerations in the antenatal care of women post-bariatric surgery include:

- All women should have detailed nutritional biochemistry due to the greater prevalence of deficiencies.2 These include iron, B12, folic acid, calcium and vitamin D. The degree of deficiency may be related to the type of surgery undertaken. Replacement should be initiated if deficits are detected.10

- Alternative methods of GDM screening may be needed, as the standard oral glucose tolerance testing may precipitate dumping syndrome.10

- In women with a laparoscopic gastric band, consider deflation of the band in pregnancy, particularly if persistent vomiting or poor weight gain occur.10

Postpartum weight reduction

Given the limited impact of antenatal interventions, focusing on the preconception or interpregnancy period may yield better results; aiming for a preconception BMI in a non-obese range, rather than trying to limit GWG.2

After delivery, many women will not return to their pre-pregnancy weight and will gain more weight prior to their next pregnancy. Even modest interpregnancy weight gains are associated with increased adverse outcomes, including pre-eclampsia, GDM and stillbirth.12 Interpregnancy weight loss reduces the risk of GDM (by almost 80 per cent),13 an LGA infant, and improves rates of vaginal birth after caesarean section.2

A systematic review showed that interventions with diet and exercise improve postpartum weight loss and reduce incidence of type 2 diabetes. No significant impact on outcomes has been seen in studies using exercise alone.2

Conclusion

Overweight and obese women are more likely to have adverse pregnancy outcomes. This risk is modifiable with optimisation of pre-conception weight and GWG. Although we are yet to understand the best approach to managing weight before and during pregnancy, we do know that addressing nutrition, improving health behaviours and managing co-morbidities in an individualised and multidisciplinary manner, can improve maternal and infant health well into the future.

References

- Callaway L, Prins J, Chang A, et al. Prevalence and impact of overweight and obesity in an Australian obstetric population. Medical Journal of Australia. 2006; 184:56-59.

- Dutton H, Borgengasser SJ, Gaudet LM, et al. Obesity in pregnancy. Medical Clinics of North America. 2018;102:87-106.

- Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, editors. Committee to Re-examine Institute of Medicine Pregnancy Weight Guidelines. Weight gain during pregnancy: re-examining the guidelines. 2009.

- 5

- Goldstein RF, Abell SK, Ranasinha S, et al. Association of gestational weight gain with maternal and infant outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2017;317:2207-25.

- Muktabhant B, Lawrie TA, Lumbiganon P, et al. Diet or exercise, or both, for preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; Issue 6. Art. No.:CD007145

- Kapadia MZ, Park CK, Beyene J, et al. Weight loss instead of weight gain within the guidelines in obese women during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analyses of maternal and infant outcomes. 2015. PLoS ONE 10(7):e0132650.

- Gunderson EP, Lewis CE, Lin Y, et al. Lactation duration and progression to diabetes in women across the childbearing years – the 30 year CARDIA study. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine. 2018; Published online January 16, 2018:E1-10

- Queensland Clinical Guideline – Obesity in pregnancy. 2015.

- Kominiarek M. Preparing for and managing a pregnancy after bariatric surgery. Seminars in Perinatology. 2011; 35(6): 356-361.

- 9

- Cnattingius S, Villamor E. Weight change between successive pregnancies and risks of stillbirth and infant mortality: A nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2016;387:558-65.

- Kim C. Maternal outcomes and follow up after gestational diabetes mellitis. Diabetic Medicine. 2014; 31(3):292-301.

Leave a Reply