In terms of global health, refugee and migrant pregnant women remain a highly vulnerable and often difficult-to-reach population. Early detection and treatment reduces maternal morbidity and mortality from malaria.

In 1990, at Sydney University, medical students learned about malaria during a one-hour lecture. There was no way at that time to know that I would spend most of my working life studying malaria, the most common parasitic infection of pregnant women. In 1994, I volunteered for a six-month job in a refugee camp called Shoklo, in the jungle on the Thai-Myanmar border. Antenatal clinics were mobile: we would carry medicine, a microscope and a blood-pressure cuff, and walk across log bridges or muddy trails, or take long tail boat rides or four-wheel drives, to meet the pregnant woman. Our clinics were bamboo and leaf: enough to keep off the hot sun or tropical downpours. Malaria was a common and sometimes devastating problem. Before the end of the first rainy season, I witnessed a maternal death from malaria in an eight-month pregnant mother of two, who initially regained consciousness with intravenous quinine and later succumbed to acute respiratory distress syndrome, a common complication of P.falciparum malaria in pregnancy.

The lifecycle of the parasite dictated that we screened women weekly. The region is notorious for a high level of multidrug resistant strains of P.falciparum malaria that left us without any drug for prevention. Women who were positive for malaria would be treated directly to prevent progression to the severe form of the disease. Birth with skilled birth attendants was provided in Shoklo camp although access issues meant many women still birthed at home. The camps for refugees still exist despite apparent political change in Myanmar and the antenatal clinics remain very popular.

Practising breech drill during 2013 ALSO course in Maela Refugee camp. (Photo by Gabie Hoogenboom.)

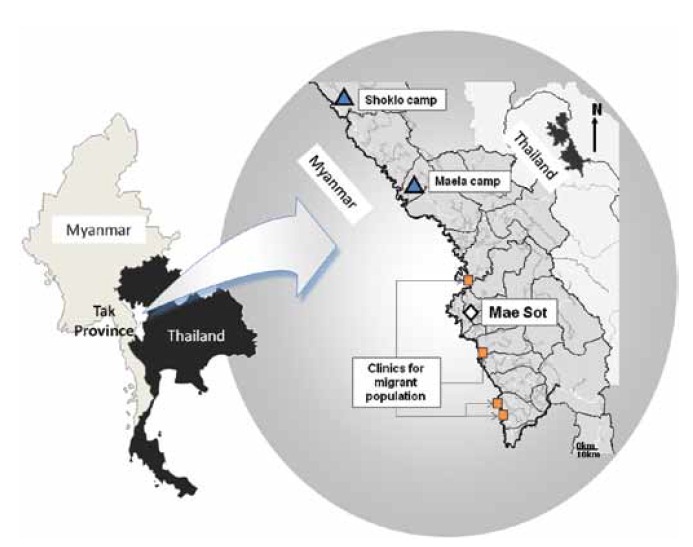

The location of Shoklo Malaria Research Unit Clinics in the refugee camp and at migrant sites on the Thai-Myanmar border. © Verena Carrara.

Taking a finger-prick sample of blood to detect malaria in a pregnant woman in Maela Refugee Camp. (Photo by François Nosten.)

Ultrasound gestational age assessment in Maela Refugee camp introduced in 2001. (Photo by Adrienne White.)

Early detection of malaria in pregnancy allows tor treatment before the disease becomes severe. (Photo by François Nosten.)

Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (www.shoklo-unit.com) falls under the scientific and logistical umbrella of the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU) based in Bangkok, and is supported by the Wellcome Trust of the UK. Malaria principally causes low birthweight and anaemia, although maternal death, miscarriage, preterm labour, stillbirth and neonatal mortality are also associated with malaria in pregnancy in this area. Maternal mortality (MMR) has fallen dramatically with the provision of early detection and treatment of malaria for all pregnant women: P.falciparum malaria related MMR in the refugee camps fell from an estimated 1000 per 100 000 (430–2320)1 in the year before the introduction of antenatal screening to zero, in 2005, and has remained at that level since.2 The decline in migrant women MMR has been less marked: 588 (100–3260) to 252 (150–430) from 1996–2000 to 2006–10. Infant mortality has likewise fallen from 250 per 1000 to <40 per 1000.3

Reducing the MMR remains one of the ongoing challenges for SMRU and much of the global community working in resource-poor settings. Many of the WHO recommendations for treatment of malaria in pregnancy have been derived from the malaria pregnancy studies conducted at SMRU.4,5 In the largest first trimester malaria study reported to date, we recently quantified pregnancy loss from P.falciparum and P.vivax infection and the effect of antimalarial drugs (chlorquine, quinine and artesunate) at this vulnerable time.6 SMRU currently provides delivery by skilled birth attendants for approximately 2500 women per year and they handle all major obstetric emergencies except caesarean section, with support from a doctor with training in obstetrics, who cannot be present 24 hours per day.7,8 The caesarean section rate is five per cent and these women are referred to the local Thai District Hospital. Life and clinical practice are different to Australia – the use of epidural in labour was rejected by the skilled birth attendants and local women are highly motivated to have vaginal delivery. We have no pain relief to offer women in labour.

Teaching and learning of skilled birth attendants in this environment has been challenging. It took 18 months for staff to be confident in the use of partogram because they were not used to reading a graph. Since 2006, some refugees have had the opportunity to resettle in the UK, USA, Canada, Norway, the Netherlands and Australia. The entire staff of skilled birth attendants needed to be replaced and training efforts intensified. SMRU has had overwhelming support and encouragement from the friendly Australia-Pacific Branch of Advanced Live Support in Obstetrics (ALSO®) since 2008. In our first year we held three ALSO participant and one instructor course in the space of two weeks. One-third of the local staff passed to Australian standards, although many have not finished school and none hold higher degrees. Most local staff struggle with the theory, as schooling in the eastern part of Myanmar has been piecemeal during 50 years of military rule. Language is a major hurdle – when English is spoken it is usually as the third or fourth language after S’kaw Karen, Poe Karen or Burmese. In 2013, Basic Life Support in Obstetrics (BLSO®) began with four courses and 74 participants. Translation of materials is frustrating, but made significantly more bearable by moments of comic relief: translation of ‘move the woman into the all-fours position’ for shoulder dystocia management came out as ‘move the woman into all four positions.’

Learning how to auscultate the pregnant abdomen during 2013 BLSO course in Wang Pha migrant clinic. (Photo by Gabie Hoogenboom.)

Routine antenatal care visit at Maela Refugee camp. (Photo by Adrienne White.)

SMRU welcomes visiting medical students or trained midwives and doctors who can come for at least eight weeks, space permitting. Staff, language and time constraints limit the number we can take at a single time. For me, somehow a planned six-month stint quickly became 19 years. I miss Australia and most things Australian and, you may think it goes without saying but it must be said, my family and friends. This is balanced by a rare opportunity to work in an amazing place alongside remarkable people, both local and foreign, who have enriched my life in more ways than I can ever hope to repay, as Confucius says: ‘Find a job you love and you’ll never work a day in your life.’

References

- Nosten F, ter Kuile F, Maelankirri L, Decludt B, White NJ: Malaria during pregnancy in an area of unstable endemicity. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1991,85(4):424-429.

- McGready R, Boel M, Rijken MJ, Ashley EA, Cho T, Moo O, Paw MK, Pimanpanarak M, Hkirijareon L, Carrara VI et al: Effect of early detection and treatment on malaria related maternal mortality on the north-Western border of Thailand 1986-2010. PLoS ONE 2012, 7(7):e40244.

- Luxemburger C, McGready R, Kham A, Morison L, Cho T, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, White NJ, Nosten F: Effects of malaria during pregnancy on infant mortality in an area of low malaria transmission. American Journal of Epidemiology 2001, 154(5):459-465.

- McGready R, Ashley EA, Nosten F, Rijken MJ, Dundorp A: The diagnosis and treatment of malaria in pregnancy. In. Edited by 54B RG-tg: RCOG; 2010.

- McGready R, Ashley EA, Nosten F, Rijken MR: The prevention of malaria in pregnancy. In: 54A RG-tg, ed.: RCOG. 2010.

- McGready R, Lee SJ, Wiladphaingern J, Ashley EA, Rijken MJ, Boel M, Simpson JA, Paw MK, Pimanpanarak M, Mu O et al: Adverse effects of falciparum and vivax malaria and the safety of antimalarial treatment in early pregnancy: a population-based study. Lancet Infect Dis 2012, 12(5):388-396.

- McGready R: Meet my uncle. Lancet 1999, 353(9150):414.

- McGready R: How a refugee community deals with adoption. BMJ 2003, 326:873.

Leave a Reply