Menopause is a clinical diagnosis made after a period of 12 months amenorrhoea, resulting from the loss of ovarian follicular activity.1 The effects of menopause on a woman’s physical, mental and emotional health are diverse. Menopause symptoms can have a significant impact on a woman’s quality of life and are a common complaint to health practitioners.

The average age of menopause is 51. Menopause is considered early if it occurs before 45 years of age, and if before 40 years of age is termed primary ovarian insufficiency, which affects approximately 1 per cent of women. When counselling a woman in this situation, is it important to address not only her menopausal complaints, but also opportunistically appraise their general health and wellbeing. Health consequences of hormonal changes at menopause include:

- Vasomotor symptoms (VMS): hot flushes; night sweats

- Urogenital and sexual symptoms: vaginal dryness and dyspareunia; vaginal itching and burning; urinary frequency and urgency; and low sexual desire

- Psychological symptoms: sleep disturbance; depressive symptoms; anxiety and irritability; reduced memory and concentration

- Physical symptoms: fatigue; headaches; myalgias and arthralgias; formication

- Metabolic changes: central abdominal fat deposition; insulin resistance; increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus; dyslipidaemia

- Cardiovascular changes: impaired endothelial function

- Skeletal changes: accelerated bone turnover and bone loss; increased bone fracture risk

Treatment principles

Always consider this an opportunity to holistically review a woman’s health. Discuss various lifestyle changes to improve general health and wellbeing, including smoking cessation, weight reduction, regular exercise and healthy diet. Important educational points include discussion of the different stages of menopause, the average duration of menopausal symptoms (approximately four years) and long-term health implications, such as osteoporosis and fracture risk and augmented cardiovascular disease risk. Advise women of the various treatment options, including menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), pharmacological options and alternative therapies.

Non-pharmacological treatments

Lifestyle interventions that show some promise of effect include meditation, cognitive behavioural therapy and relaxation techniques. Lifestyle modifications that promote general wellbeing should also be encouraged, including regular exercise, smoking cessation and weight reduction. These may help improve some bothersome symptoms, as well as reduce a woman’s risk factors associated with either menopause itself or MHT use. Additional self-management strategies include dressing in layers and avoiding VMS triggers, such as excessive alcohol and caffeine intake.

MHT

The primary indication for MHT is for the relief of troublesome menopausal symptoms, typically VMS. All women with a uterus must receive progestogen supplementation in addition to oestrogen to prevent the dose-dependent risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer with unopposed oestrogen use. Women who have had a hysterectomy may receive unopposed oestrogen, which can be beneficial in terms of reducing breast cancer and coronary heart disease risk.2 Women who present with only vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) symptoms may be treated with local low-dose oestrogen without the need for any progestogen cover.

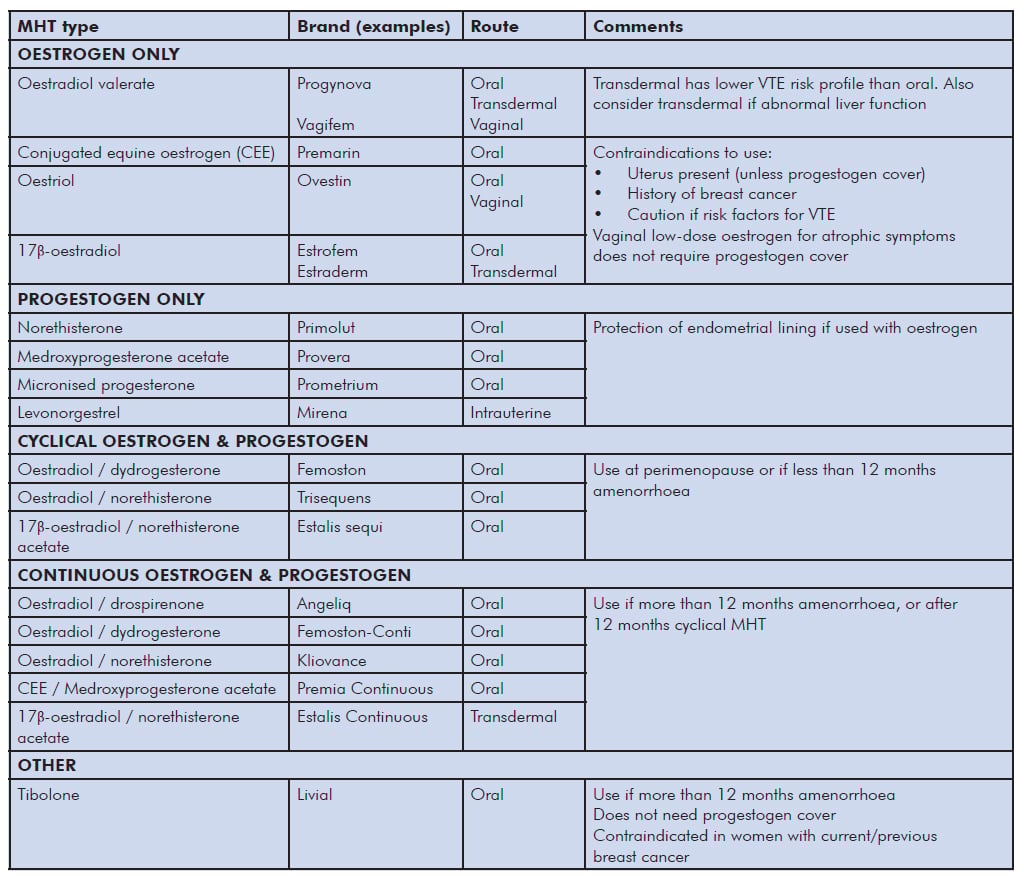

MHT preparations vary in terms of type of hormonal preparation; dose; route of administration, including oral, gel, transdermal, vaginal and intrauterine; and whether they are used as a continuous or sequential regime. The use of MHT should be with the lowest dose that achieves symptomatic relief and for the shortest duration possible. Women receiving MHT should have at least annual review by their practitioner, including physical examination, an update of the woman’s personal and family history, any investigations as appropriate, and discussion regarding lifestyle measures that may improve their symptoms as well as their general health. There is no need to place an arbitrary limit on the duration

of MHT use. The Women’s Health Initiative study has demonstrated safe use of MHT for at least five years in healthy women under the age of 60. Ongoing review beyond five years, or initiating MHT over the age of 60 or more than 10 years after menopause, needs individualised assessment of potential risks versus benefits. Unscheduled vaginal bleeding in women with a uterus may occur within the first three months of commencing MHT; however, further investigation is warranted if this persists beyond three months.

Table 1. MHT options.

Overall MHT benefits

- Most effective treatment for VMS and VVA

- Prevents menopause-associated acceleration of bone loss and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. This protection is also conferred by tibolone and SERMs (for example, raloxifene, bazedoxifene). This protection declines after cessation of MHT.2 Improvement in cardiovascular disease risk if commenced before age 60 or within 10 years of menopause. Evidence suggests that oestrogen-only MHT is cardioprotective, especially if commenced around the time of menopause (the ‘window of opportunity’ phenomenon); while combined MHT has shown a nonsignificant improvement in coronary artery disease.3

- Reduced colon cancer risk, conferred by both combined MHT and tibolone use.3

- Alzheimer’s disease – MHT initiated around the time of menopause has shown a reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.1

Overall MHT risks

- Breast cancer – this is a complex issue and data are conflicting. The possible increased risk of breast cancer with MHT use is small (approximately one extra case per 1000 women using MHT for one year). This risk decreases after cessation of MHT. The risk is mostly attributed to the addition of progestogen to oestrogen therapy and related to duration of use.4 MHT use in breast cancer survivors is not recommended, owing to a lack of safety data to support its use.

- Endometrial cancer – unopposed oestrogen induces a dose-dependent stimulation of the endometrium, increasing the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and malignancy. This risk persists for years after cessation of use. The addition of progestogen counteracts this.1

- Ovarian cancer – the only RCT evidence available3 does not show any increased risk with MHT use. A recent meta-analysis5 has shown a very small increased risk; however, this is from a heterogeneous mix of observational data.

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE) – risk with MHT use is age related, as well as influenced by BMI and other prothrombotic factors. Absolute risk is rare in women less than 60 years of age. VTE risk, including the risk of ischaemic stroke, is greatest within the first few years of use and with oral, compared to transdermal, administration.1

Tibolone

Tibolone is a synthetic steroid hormone exhibiting oestrogenic, progestogenic and androgenic properties. Beneficial effects of tibolone include improvement in VMS, reduction in bone loss and spinal fractures, endometrial protection, it improves VVA and may improve low libido. Tibolone should not be used in addition to any MHT, rather as an alternative. Side effects may include headache, acne, increased hair growth and occasionally, irregular bleeding. Tibolone has not been shown to increase a woman’s risk of VTE, breast cancer, endometrial cancer or cardiovascular disease. Some research suggests an increased risk of stroke in women over the age of 60.

Non-hormonal options

Pharmacological options available to treat VMS are limited. To date, gabapentin is the only non-hormonal agent with equivalent efficacy to MHT for treating VMS; however, its use is often limited due to side effects such as drowsiness, headaches and gastrointestinal upset. Other pharmacological options with less efficacy include antidepressants, such as venlafaxine, and clonidine, an alphaadrenergic agonist traditionally used as an antihypertensive. These options are particularly useful in women wanting to avoid hormonal therapy either due to medical concerns, such as a personal or family history of breast cancer, or due to personal preference. While these options are less effective in reducing VMS compared to MHT, they have their place in the treatment of postmenopausal women.

Alternative therapies

Women may often present seeking complementary or natural therapies to aid their menopausal symptoms. The difficulty with counselling women regarding ‘natural’ hormones and other complementary therapies is the lack of clear objective evidence regarding their performance and safety. Many trials exist; however, the results are largely mixed. The ingredients in complementary and herbal remedies may not be stringently regulated in terms of dosage and proven efficacy and may lack rigorous safety testing. For these reasons, careful counselling is required when women enquire about alternative treatments for VMS, such as phytoestrogens and black cohosh.6

The decision to initiate, and then to continue or cease, MHT needs to be made by an informed woman in conjunction with her informed medical practitioner. Key issues to consider are the desired treatment goals, symptom severity, the woman’s individualised risk profile and her personal preferences. A wealth of resources exist to guide women and medical practitioners in these decisions; however, careful appraisal of the evidence is required.

Menopause is an important clinical issue of which every gynaecologist should have a clear understanding. Given the potentially significant impact that menopause and its symptoms can have on many facets of a woman’s life, it is vital that gynaecologists are able to manage this period holistically and confidently.

References

- De Villiers TJ, Pines A, et al. Updated 2013 International Menopause Society recommendations on menopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife health. Climacteric. 2013;16(3):316-37. DOI: 10.3109/13697137.2013.795683.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Menopause: diagnosis and management [Internet]. NICE; 2015 [cited 2016 Dec 21]. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23.

- Writing group for the Women’s Health Initiative investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321-33.

- De Villiers TJ, Hall JE, Pinkerton JV, et al. Revised Global Consensus Statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric. 2016;19(4):313-5. DOI: 10.1080/13697137.2016.1196047.

- Collaborative group on epidemiological studies on ovarian cancer. Menopausal hormone use and ovarian cancer risk: individualised participant meta-analysis of 52 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 2015;385:1835-42. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61687-1.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Menopause: diagnosis and management [Internet]. NICE; 2015 [cited 2016 Dec 21]. Available from: www.nice. org.uk/guidance/ng23.

Leave a Reply