Every tradesperson needs a range of tools at their side and in medicine, particularly in obstetrics and gynaecology, surely one of the most valuable and powerful tools in our toolbox must be that of research synthesis, a process that underlies many of the principles of best clinical practice and evidence-based medicine (EBM). This article will trace the history of research synthesis and explain its key components, in addition to considering its pros and cons.

What is research synthesis?

As busy clinicians, every day we need to make decisions about which treatment or intervention is the best for a particular patient with a particular problem. Without any form of research synthesis (defined, in its most primitive form, as a way of integrating empirical research)1, we would not be able to know which treatment or intervention is the best for our patient. The term research synthesis may also be defined as: the process by which two or more research studies are assessed, with the objective of summarising the evidence relating to a particular question. The processes that result in or encompass a research synthesis may be referred to using a range of terms, with which may be confusing to the novice. In addition to a number of terms being used, there are a range of different options or elements, which may be used in combination or as standalone tools.

Where does it come from?

Research synthesis emerged at the start of the 1900s, with the publication of key research synthesis papers in the field of typhoid, an important public health issue at the time.1 EBM is a term that may be more familiar than research synthesis. EBM may be defined as: the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.23

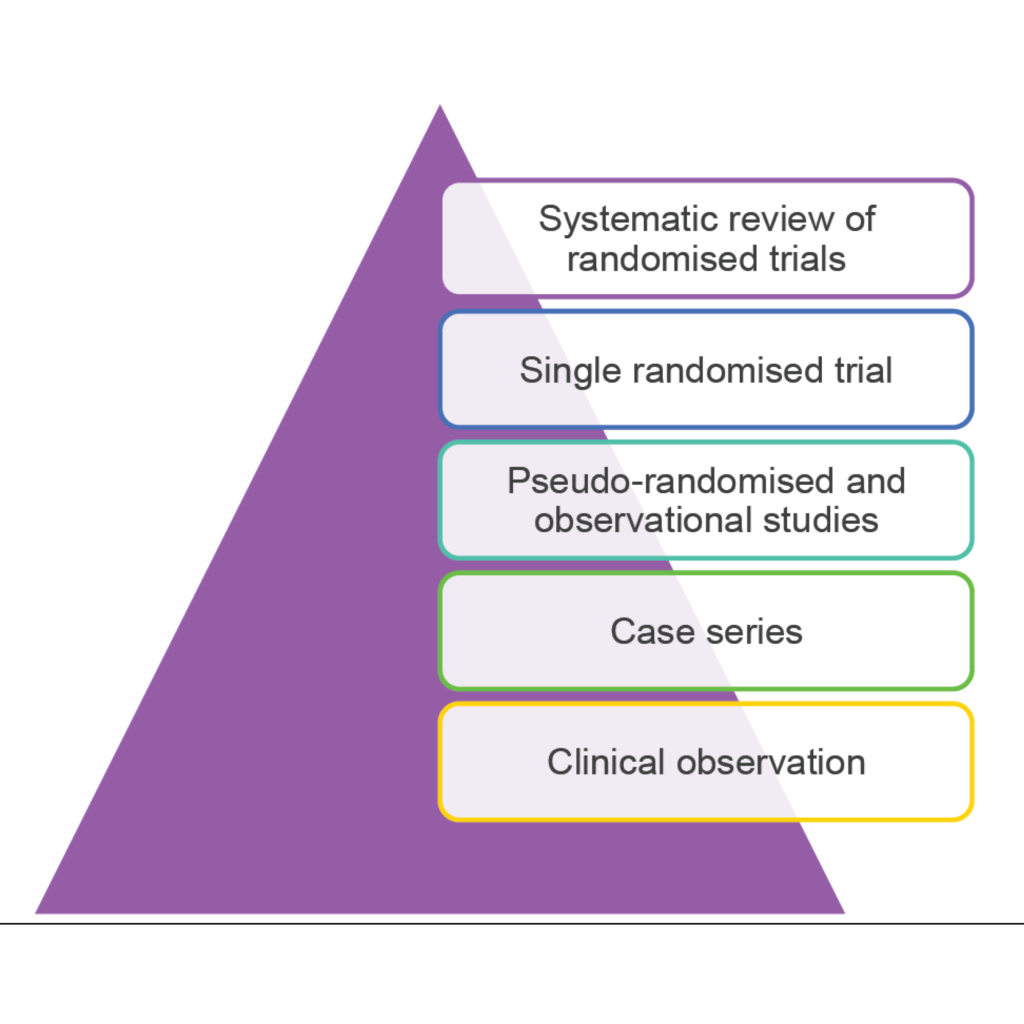

EBM, research synthesis and their related principles can be further traced to the writings of French physician, Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis, who encouraged practitioners not to rely on ‘speculation and theory about causes of disease nor…single experiences’, but rather to make a ‘large series of observations and derive numerical summaries from which real truth about the actual treatment of patients will emerge.’4 This real truth is derived, in part at least, from our ability to use the tools of research synthesis that allow us to build the top of the research evidence pyramid. Research synthesis allows us to take the idea of deriving (numerical) summaries to a much more sophisticated level5 and to build the top floors of the research evidence pyramid by minimising bias as far as possible. The now well-known hierarchy or pyramid of research evidence ranks research methodologies based on how well potential biases are minimised (see Figure 1) and identifies systematic reviews of randomised trials to be of the highest possible quality. The process of undertaking a systematic review can be understood as way of synthesising research, or one type of research synthesis, but there are other aspects to consider.

Figure 1 – The hierarchy or pyramid of evidence-based medicine. Adapted from: NHMRC levels of evidence and grades for recommendations, December 2009

Types of research synthesis

The most basic form of research synthesis is one that almost all will be familiar with, that of the literature review. In a traditional literature review, the author is often an expert in the field and provides little information as to how the review was conducted or the scientific basis of any recommendations.6 The author of a traditional or narrative review will often express his or her opinion and take a less-than-systematic approach to their review of the literature.

Systematic review, a frequently used term since the 1990s, in fact is a concept dating back to the early 20th century7, although it almost certainly has different implications now and has evolved into a much more rigorous process. Our common understanding of the term systematic review can perhaps be attributed to Archie Cochrane in the introduction to the first bible of evidence-based care in obstetrics, Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth.8 Systematic reviews aim to identify, evaluate and summarise the findings of all relevant individual studies9 and in their most pure form adhere to a strict scientific design, based on explicit, pre-specified and reproducible methods. However, the term systematic review is often more generally used to mean a process of literature review by which measures are taken to reduce the influence of bias. Systematic reviews are often performed alongside of, and even confused with, an additional, but separate, quantitative process of research synthesis known as meta-analysis. Meta-analysis, a term coined in the 1970s, is used to refer to ‘the statistical analysis of a large collection of analysis results from individual studies for the purpose of integrating the findings.’10

Why do we need research synthesis?

We are all busy in our clinical day-to-day lives and most of us lack the time and inclination to search for, identify and appraise original research when looking for the answer to our clinical questions. Many studies may be available when searching for the answer about a particular clinical question; we need to put together their results in a sensible way. Research synthesis allows us to review and make decisions about clinical questions in a timely way.

Pros and cons of research synthesis

With advanced methodologies and approaches to assessing and summarising all forms of original research – including qualitative and cohort studies, not only randomised trials – research synthesis is applicable to all types of research11 and, indeed, to all areas of interest in our field of women’s health.

The concept of a single, systematic review or any other piece of research synthesis providing the answer to a clinical question is somewhat of a fallacy, with many systematic reviews and meta-analyses raising and generating more questions than are answered. In fact, systematic reviews and meta-analyses that identify ‘gaps’ in the literature are often used as the basis to formulate new ideas and plan future research. It has been stated: ‘Evidence does not speak for itself – it requires interpretation in light of its original context [and] limitations…in order to inform the practical decisions of other [clinicians].’12 In view of this, clinicians require training to be skeptical and discriminating, to develop the skills required to make the best use of research synthesis and then generate positive changes in clinical practice to improve health outcomes.13

References

- Chalmers I, Hedges L and Cooper H. A Brief History of Research Synthesis. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 25(1); 12-27, March 2002.

- Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992; 268(17):2420-2425.

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal 1996;312(7023):71-72.

- Cochrane A. Effectiveness and efficiency. Random reflections on health services. The Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust 1972.

- Cooper H and Hedges L. Research Synthesis as a Scientific Process. Chapter 1, from The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, Second Edition. Feb 2009. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Grimshaw J. A knowledge synthesis chapter. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/knowledge_synthesis_chapter_e.pdf

- Chalmers I, Hedges L and Cooper H. A Brief History of Research Synthesis. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 25(1); 12-27, March 2002.

- Chalmers I, Hedges L and Cooper H. A Brief History of Research Synthesis. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 25(1); 12-27, March 2002.

- Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, 2008. Published by CRD, University of York. January 2009.

- Chalmers I, Hedges L and Cooper H. A Brief History of Research Synthesis. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 25(1); 12-27, March 2002.

- Grimshaw J. A knowledge synthesis chapter. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/knowledge_synthesis_chapter_e.pdf .

- Cook DA. Randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis in medical education: What role do they play? Med Teach. 2012 Apr 10. [Epub ahead of print].

- Gilbert R, Burls A, Glasziou P. Clinicians also need training in use of research evidence. Lancet. 2008; 371(9611):472-3.

Leave a Reply