The identification of ambiguous genitalia at birth is often the cause for significant distress and concern. It poses challenges for the health professional in the labour ward or in the operating theatre at the time of caesarean section, but, more importantly, it is the cause for significant distress to parents who are about to be asked by family and friends – did you have a girl or a boy?

The initial response by the health team is crucial for optimal outcomes, as this sets the tone for management and future parental attitudes, with an impact extending beyond the parents and on to

their child.

Ambiguous genitalia can be the earliest feature of a Disorder of Sex Development (DSD), which covers a wide range of conditions where the chromosomal, gonadal or genital development is atypical.1 In general, 1:4500 babies will be born with atypical genital appearance.2 3 The incidence of ambiguous genitalia differs according to the definition used. As clinicians involved in the care of pregnant women and neonates, we need to have an awareness of underlying cause and the ability to manage or refer with confidence.

Although the commonest cause for ambiguous genitalia is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) in 46XX individuals, the diagnosis and management of patients with ambiguous genitalia can nevertheless be challenging and will require a multidisciplinary approach. This is an area fraught with emotional and management challenges for the clinician and family alike, both of whom may not have encountered this issue before.

There is a growing cohort of patients who are now being identified antenatally; both with the use of careful ultrasound scan (USS) where genital variations and anomalies may be noted, and with non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT). One such example of a prenatal DSD now being diagnosed at birth is the phenotypically female baby with a known 46XY karyotype – a girl with 46XY complete gonadal dysgenesis, who more commonly would have come to medical attention with delayed puberty. Additionally, there are baby girls being identified on ultrasonography with what appears to be a prominent clitoris, raising suspicions of CAH.

We have designed this to be a simple guide to the approach, diagnosis and early management of neonates with ambiguous genitalia. We have intentionally omitted a detailed outline of genital embryology or the pathophysiology of the various DSDs.

When the USS identifies clitoromegaly

Referral for discussion with a paediatric endocrinologist with a simultaneous referral to a DSD coordinator or social worker for support would be appropriate. The identification of a potential problem in the infant will provoke anxiety in the parents and early intervention and support is best-practice care. (See further management at birth below).

First encounter – how to respond and what you shouldn’t miss

This situation usually arises immediately after the birth of a newborn. Despite huge social pressure, care providers should avoid the temptation to assign sex when there is any ambiguity present. The language we use is vitally important and it can take time and practice for all staff to be comfortable with use of ‘they’ (when referring to the baby) or ‘your baby’ rather than he or she.

Examination and diagnostic investigations

Detailed family and prenatal history, followed by thorough physical examination for associated dysmorphic features, pigmentation, palpable gonad(s) and external genitalia appearance (including symmetry of the genitals, the site of the urethral opening, the presence of a hymen and vaginal opening or the presence of a urogenital opening) is required.

Samples for karyotype and fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) testing should be sent immediately, as this rapidly helps to sort out potential diagnoses. Electrolytes and 17-OHP can be sent on day one or two as blood is being taken, but the 17-OH progesterone is best on day three and electrolytes are most important on day five. If they are done on day one to three, they may be normal, and will need to be repeated. In many cases the FISH result will be back within 24–48 hours, and if the result reveals an XY karyotype, then you will no longer be chasing a diagnosis of CAH with its incumbent risk of a life-threatening adrenal crisis.

Hormone panels (FHS, LH, oestradiol, testosterone and AMH) are useful for determining function of the gonadal tissue. Further investigations depend on results and will be tailored towards defining the most likely cause.

Pelvic USS can give an indication of location of gonads. It should be mentioned that neonatal uteruses and gonads are more easily identified earlier on, although some care in making decisions based on this is always warranted. Occasionally, a laparoscopy is required for gonadal biopsy and more detailed examination of internal and external anatomy.

Most common causes

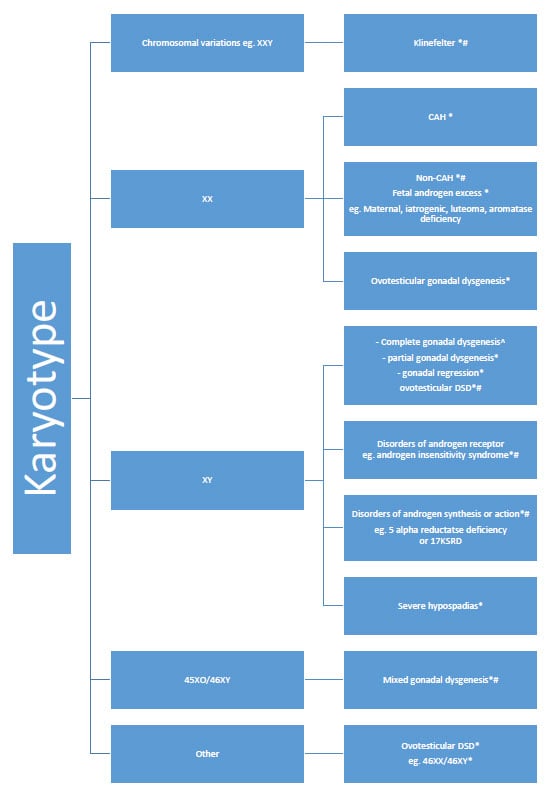

Figure 1 gives possibilities for diagnosis divided by karyotype. Physical examination, history, biochemical testing and laparoscopy (if indicated) help to differentiate between diagnoses. Details of each specific condition are beyond the intended scope of this article.

Figure 1. DSD causes associated with ambiguous genitalia grouped by karyotype (this is not an exhaustive list).

^ Antenatal NIPT with discrepancy of phenotype at birth (no ambiguity)

* Ambiguous genitalia at birth

# Virilisation at puberty

Early management

A multidisciplinary approach, with clear communication to the family, is essential. Neonates presenting with ambiguous genitalia should be referred to paediatric endocrinology, paediatric surgery and, if necessary, paediatric gynaecology, for investigative planning.4 These teams should have psychological supports available for the family, although local social work support may also be appropriate.

The management of ambiguous genitalia has changed over time. Many more babies are raised male now, where there has been under-virilisation of a 46XY baby. Considerable debate continues regarding undertaking feminising genitoplasty, but extensive discussion with the family is likely to occur between the DSD team and the parents.

The removal of gonads has also shifted substantially, with efforts now to define the malignancy risk, often with biopsy looking for some specific genetic markers. For gonads that are non-functioning, with no fertility potential and a malignancy risk, removal remains appropriate (for example, 46XY GD, 45XO/46XY with a female phenotype). However, the testes in someone with complete androgen insensitivity are usually left in situ today as they are hormonally active (producing testosterone that is converted into oestrogens at puberty) and removal is only considered after puberty; and even then, there is the option of monitoring the testes for change, rather than removing. Removal of testes in a girl presenting at puberty with virilisation is also not a decision to be fast-tracked; the process of using GnRH agonist while careful consideration and discussion between the young person and the DSD team is the more appropriate approach today, allowing for time for the individual to be mature enough to be involved in the decision-making process.

For more information on this topic, Department of Health Victoria has a wonderful, user-friendly guide to the management of ambiguous genitalia in neonates. It can be found at www2.health.vic.gov.au/hospitals-and-health-services/patient-care/perinatal-reproductive/neonatal-ehandbook/congenital-abnormalities/ambiguous-genitalia.

Presentation in childhood

Some children’s genital ambiguity is not detected until later in infancy or childhood. Sometimes this is because the changes were subtle and not recognised, other times it may be due to poor access to healthcare.

Care needs to be taken regarding language. Again, karyotype, 17 OH progesterone, FSH, oestrogen, testosterone and AMH are a good start, along with referral to a specialist team for assessment and care. A USS or MRI reporting on the presence or absence of a uterus in this age is very unreliable.

Presentation at puberty

Young women with non-classical CAH may present with some virilisation, acne and amenorrhoea, although may also present with infertility and minimal virilisation. In conditions where there is some testicular tissue present, the onset of puberty-increased production of testosterone will cause virilisation (in association with amenorrhoea). Conditions such as partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, 5α-reductase deficiency and 17 KSRD are the most likely. Your choice of words here will be critically important. Referral to a multidisciplinary team, where full discussions regarding decisions and options can be undertaken, is appropriate. For young women, there is mounting evidence that support groups are very helpful. Most DSD teams will have appropriate links available for young women.

Conclusion

Your language and response as the first clinician involved with the family, baby, child or teenager is vitally important. Our society continues to place a lot of emphasis on gender. The family will need your supportive care in those first few days of uncertainty. Clear and open communication is essential. We have found that the vast majority of families with a child or adolescent who has ambiguous genitalia manage this uncertainty well when they are provided adequate support through each step of the process.

References

- Ocal G. Current Concepts in Disorders of Sexual Development. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinology. 2011;3(3):105-14.

- Ocal G. Current Concepts in Disorders of Sexual Development. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinology. 2011;3(3):105-14.

- De Paula GB, Barros BA, Carpini S, et al. 408 Cases of Genital Ambiguity followed by single Multidisciplinary Team During 23 Years; Etiologic Diagnosis and Sex of Rearing. Int J of Endocrinol. 2016;2016:4963574. doi:10.1155/2016/4963574.

- Rascol N. Disorders of Sexual Development; A cryptic combo of care. Professional Med J. 2015;22(4):401-7.

Leave a Reply