Every practitioner should have a documented procedure for cleaning ultrasound probes, with the dual aims of preventing infection transmission and prolonging the life of the probe.

General considerations

- When considering which processes and products to use for probe cleaning, always make sure that you check your institutional infection control guidelines (where relevant), as these may vary between institutions. Products used for disinfection should be approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for use on medical devices and approved by the manufacturer of the transducer. Consult the manufacturer’s website for a list of approved disinfection methods for each transducer, as they may vary even between products in the same range.

- All residue on the probe, such as ultrasound gel, should first be removed to optimise the efficacy of the cleaning process. Any grooves or crevices should be cleaned with a soft brush prior to disinfection.

- Be aware that probes are fragile and regular use of abrasive cleaning methods (even towels), heat or non-approved disinfectants can degrade the probe.

- Check the probe regularly for cracks or other signs of damage and contact the manufacturer immediately if damage is found.

- Be alert to the risks of cross-contamination to the surrounding environment, including hands, transducer cables, consoles and furniture. Handle probes and remove and dispose of covers carefully, adhere to hand hygiene protocols and wipe other surfaces regularly.

- Many outbreaks of infection in ultrasound departments have been attributed to contamination of ultrasound gel. Non-sterile gel from multi-use bottles should only be used for transabdominal examinations; for transvaginal scanning or for a patient with a potentially transmissible infection, single use sterile gel sachets should be used. Lids should be closed on disposable gel bottles after each use, and they should be emptied and thoroughly washed on a regular basis.

What is the evidence for infection risk?

Failure to follow appropriate infection control procedures when using ultrasound has led to numerous documented infectious outbreaks.¹ Of particular concern in the context of transvaginal scanning are organisms such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Treponema pallidum, Mycoplasma genitalium, Trichomonas vaginalis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis and herpes viruses, and human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV can persist in the environment and retain a high proportion of infectivity for 7 days.¹

Probe covers protect against infectious contamination of ultrasound probes, but, due to the risk of breakage or micro-perforations, disinfection procedures must still be followed. In general, commercial non-latex probe covers probably perform better than condoms, but still have leakage rates up to 5%.² Probe covers also do not protect transducer handles, which were shown in one study to have a 98.8% rate of bacterial contamination after routine use. Disinfection procedures must therefore include the entire transducer, including the handle.³

Abdominal transducers

Abdominal transducers are classed as non-critical medical devices under the Spaulding classification system for medical devices¹ because they come into contact with intact skin. As such, they require low level disinfection (LLD) after each use. After removal of gel, they should be cleaned with a TGA-approved disposable cleaning wipe or system intended for use on medical devices.

If an abdominal transducer is used on infected or non-intact skin, a transducer cover should be used and high-level disinfectant procedures should be followed. For interventional procedures, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS), sterile transducer covers should be used, and high-level disinfection (HLD) procedures should be followed if there was any possibility of the probe or its cover contacting body fluids during the procedure.¹

Transvaginal transducers

Because transvaginal transducers come into contact with mucous membranes, they are classified as semi-critical medical devices under the Spaulding classification and require HLD. HLD procedures aim to eliminate all pathogens except bacterial endospores. Methods for HLD that are approved for use in Australia include:

- Automated high-level disinfection systems:

- ultraviolet disinfection systems (eg Germitec, Lumicare): the transducer is placed in a closed cabinet and exposed to high-intensity ultraviolet type C radiation

- chemical disinfection systems (eg Nanosonics): sonicated hydrogen peroxide mist.

- Liquid high level instrument grade chemical disinfectants (eg Opal): ortho-phthalaldehyde.

- High level instrument grade disinfectant wipes (eg Tristel).

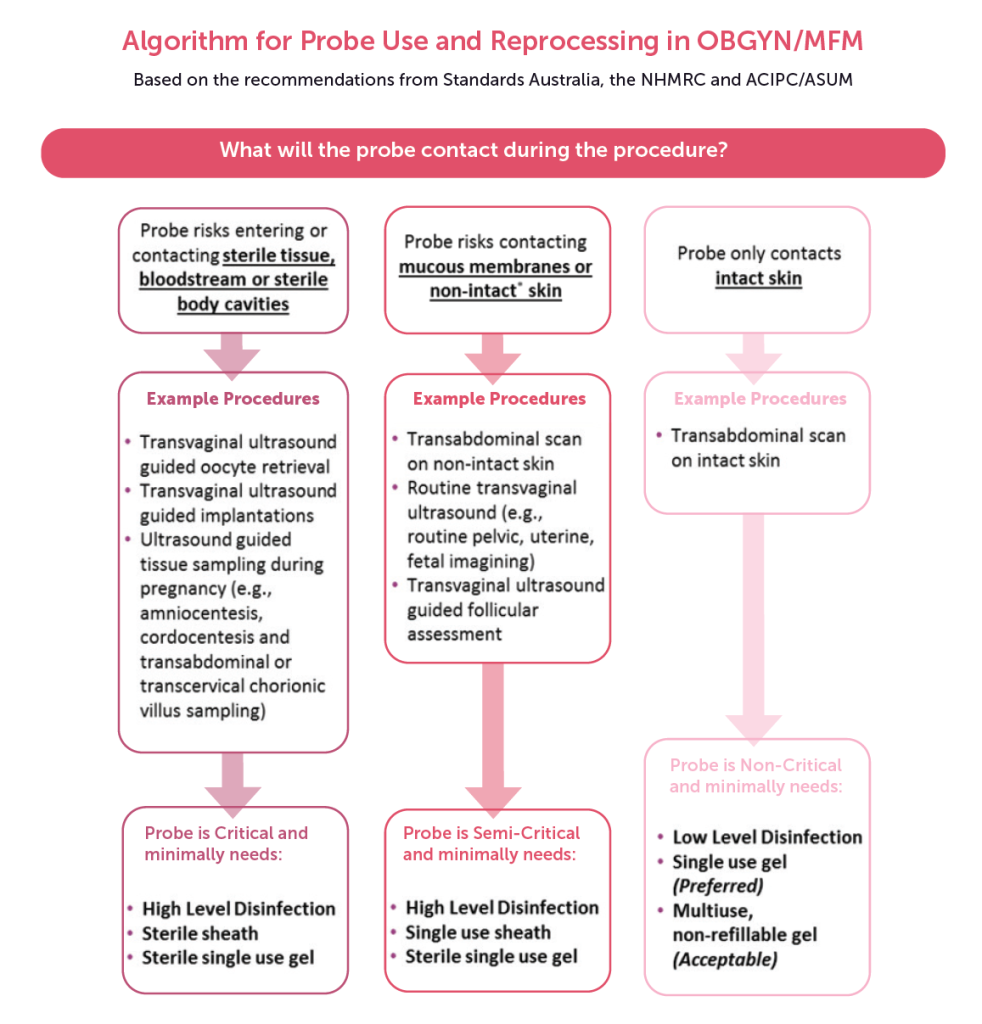

Figure 1. Algorithm for probe use and reprocessing in OBGYN/MFM. Source: https://www.ultrasoundinfectionprevention.org.au/.

Automated HLD systems are less prone to operator error than manual systems and eliminate concerns about toxic fumes or spillage. A 2015 study showed superior performance of an automated disinfection system compared with a manual disinfection process involving disinfectant wipes, although use of wipes in this study did not include routine wiping of instrument handles.³ However, automated systems are expensive to purchase and for this reason tend to be used mainly in practices that perform a high volume of semi-critical scans.

Records of HLD must be kept to ensure traceability in the event of decontamination failure. See the ASUM Guidelines on Reprocessing Ultrasound Probes¹ for details of documentation requirements.

Following disinfection with chemical disinfectants, transducers should be rinsed with water and dried with a disposable low-lint cloth. They should be stored in such a way as to prevent environmental contamination, either in a specific cabinet or covered with a clean, disposable cover.

References

- Australasian Society for Ultrasound in Medicine (ASUM). Guidelines for reprocessing ultrasound transducers. Australas J Ultrasound Med 2017;20(1):30–40. doi:10.1002/ajum.12042

- Basseal JM, Westerway SC, Hyett JA. Analysis of the integrity of ultrasound probe covers used for transvaginal examinations. Infect Dis Health 2020;25(2), 77–81. doi:10.1016/j.idh.2019.11.003

- Buescher DL, Möllers M, Falkenberg MK, et al. Disinfection of transvaginal ultrasound probes in a clinical setting: comparative performance of automated and manual reprocessing methods. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;47(5):646–651. doi:10.1002/uog.15771

Leave a Reply