Many of us who get towards the end of our O&G career pause to reflect on achievements and endof- career direction and plans. In 2013, I decided to give up after-hours private practice and sell my last interests in a private hospital I had built in the 1980s and 90s. Instead, I chose to focus on training the next generation of doctors, and other strategies to improve maternal and newborn outcomes across Papua New Guinea (PNG).

In a low-income country like PNG, the major impact on maternal and newborn care outcomes is to be made by providing quality midwifery and newborn care near where women live: 85% of people in PNG live in rural areas.

In 2012, I teamed up with the late Dr Lahi Geita – a colleague in the National Department of Health – to train our basic rural nurse, known as a community health worker (CHW), to provide quality maternal and newborn care. A pilot training program at Mt Hagen Base Hospital involved six months on-the-job, inservice training, with strict selection criteria to ensure that the graduates returned to their rural health facility after completing training.

To date, there have now been over 20 such trainings conducted in groups of 7–10 CHWs, in 14 provincial hospitals around PNG. In total, 320 CHWs have been upskilled in this program to provide quality maternal and newborn care in the context of rural PNG.

The O&G unit at the Port Moresby General Hospital (PMGH) in the national capital, where I spend 90%of my professional time, recorded an increase in its numbers of annual births of about 10% between 1978 and 2016.1 In 2016 we were offered some reproductive health assistance by the DAK Foundation, an Australian philanthropic trust. My professional colleagues (midwifery and medical) and I decided that the best way we could use this support was to set up an immediate postpartum familyplanning implant program.

Since 2017, the numbers of women presenting to the PMGH labour ward for supervised birthing care has plateaued at around 14,000. If it had kept on rising by 10% per year (as occurred between 1970 and 2016), we would by now be overwhelmed by more than 25,000 women per year seeking supervised birthing

care in a facility designed to provide care for 10,000 (as there is no other public maternity facility in the national capital, Port Moresby).

PMGH O&G division also offers immediate postpartum tubal ligation and vasectomy services, and about 1,800 couples avail themselves of this family-planning completion strategy, annually. Along with the 5,000 implants per year we now provide, this means that almost half of women birthing at PMGH return home with an effective method of long-term contraception. We estimate that less than 10% of the remainder subsequently attend city family-planning clinics to start a modern method of contraception.

More than 90% of women who go on to deliver at PMGH receive regular antenatal care in Port Moresby’s clinics – including 5,000 per year who attend the public hospital clinic. These women receive some of the best maternity care in the world, despite many human and resource constraints. The perinatal mortality rate (PMR) among ‘booked’

mothers at PMGH maternity is generally less than half that of similar-sized public maternity units in other low- or middle-income countries. The maternal mortality ratio is similarly low.

For booked mothers at PMGH:

- the PMR is less than 20/1,000 births

- the MMR is about 50/100,000 live births

This is achieved with possibly the lowest intervention rates in the world, with a caesarean section rate of 5%, assisted vaginal delivery rate of 5%, and induction of labour rate of 5%.2

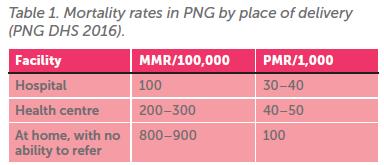

On the other hand, the supervised birth proportion for the rest of PNG is shamefully low, at less than 40%, and has remained static at this level for more than 20 years. Women who are unable to get a supervised birth have a ten-fold risk of dying in childbirth. Their babies have a three-fold risk of death, and also a higher rate of non-fatal birth trauma, often with life-long consequences (see Table 1).

To improve this, it is critical to increase the proportion of women choosing to deliver at rural health facilities, rather than remaining in their rural village homes. Of the 360,000 births annually in PNG:

- 30% are supervised in 22 provincial hospitals (including PMGH)

- 10% occur in approximately 800 rural health facilities (equating to less than one birth per week in most of them)

The provincial hospitals are overcrowded, and the rural health facilities are very under-utilised. Clearly, if we are to improve the proportion of women accessing supervised birth services, more women need to utilise the rural health facilities near their homes.

About 10 years ago I decided that my retirement would be more meaningful if we could achieve supervised birthing services for the rural majority of women who are currently at risk of morbid outcomes for both themselves and their newborns.

Over the past 10 years, these trainings and rural health centre upgrades have been made possible with funding from various support agencies, including church agency health services and nongovernment organisations (NGOs), such as DAK Foundation, Soroptimists International, and the Mola Foundation. Government and United Nations agencies have also helped, including AusAid, United Nations Population Fund (UNPF) and UNICEF.

Local provincial health authorities in PNG have also contributed significantly by helping to select suitable CHWs for training, and by paying their salaries for six months during the in-service training program.

Setting up for success

To encourage women to come to their rural health facility, there needs to be:

- Well-trained health workers to provide quality maternal and newborn care;

- Rural facilities with the capacity to provide quality care for birthing women 24 hours per day.

Initially, we hoped that decent facilities and well-trained staff would be sufficient to alter the behaviour of women and their families; to swap their traditional view of home births for a journey to their local rural health facility for a safer supervised birth. Initially, this did not happen; most of rural health facilities remained under-used.

So, in 2019, I decided that we should try an additional motivational strategy that was based on an idea pioneered in Finland and Cambodia to incentivise rural supervised birth. The latter country managed to increase the supervised birth proportion from about 35% to 75% over five years in the late 1990s, by incentivising supervised birth in rural areas. Additionally, a pilot incentivisation program underway since 2009 in Milne Bay province (PNG) had doubled supervised birth numbers in 15 participating rural health facilities.3

Also in 2019, we initiated a ‘baby box’ program, complemented with food supplies, to eight rural health facilities in Simbu province in the highlands of PNG. The baby box contains everything that a family might need, all wrapped in large plastic baby bath, including:

- Baby: nappies, pins, blanket, booties, vest, towel

- Mother: sanitary pads, soap, umbrella, new sarong

- Father: a file to sharpen an axe, and a new spade

Also supplied is brown rice, tinned tuna, and coins for the nurse to purchase greens in the local market for the women and their accompanying family – usually the husband and last-born child. Without food to eat, pregnant women are unable to stay around the ‘mama waiting houses’ in the rural health facilities for the onset of labour.

This program has now been running for three years, and in this time, most of the participating rural health facilities have seen a more than doubling in the numbers of women attending for supervised birth.

Epidemiologically, it is estimated that one woman’s life is saved for every additional 150 women who come for supervised birth, and one newborn is saved for every 20 additional women who come for supervised birth in their local rural health centre.

Over the three years of this program’s life, it is estimated that incentivisation for this improved level of delivery care has averted 20 maternal deaths, and 150 newborns lives have been saved. These benefits do not include improvements in morbidity, increased numbers of women who accept immediate postpartum contraceptive implants, and referral to the provincial hospital for postpartum tubal ligation.

The cost of this program is modest: about $3,000 per rural health facility each year, depending upon the numbers of supervised births in the facility. Support of eight rural health facilities enables an additional 1,000 women per year to have a facility-supervised birth by a health professional. I am hoping that we can extend this work to other provinces of PNG soon.

In the long run, improved survival of mothers and children, especially if accompanied by a further reduction in the birth rate, should help to trigger feedbacks that improve wellbeing and prosperity in PNG. These are benefits that Maurice King (in the 1960s, the man who was responsible for changing the world public health paradigm to a focus on ‘community medicine’) and his colleagues and supporters have long alluded to.4,5

DAK Foundation: https://dak.org.au Soroptimists International: www.soroptimistinternational.org

Mola Foundation: www.perpetual.com.au

References

- Mola GDL, Unger H. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;59:394–402.

- Port Moresby General Hospital, O&G Department Annual Reports, 2000–2021.

- Robson S, Kirby B, Mola GDL, Case C. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55:291–3.

- King M. (1966). Medical Care in Developing Countries. Oxford University Press.

- King M, Mola GDL. (2023). Primary Mothercare and Population (3rd ed.) Practical Action Publishing.

Leave a Reply