The postpartum bladder is commonly afflicted by injury and infection, and the associated shortand long-term sequelae can be debilitating. Our understanding of the normal, and abnormal, postpartum bladder is unfortunately incomplete1,2 and thus the diagnosis and management of early postpartum bladder issues, such as urinary retention, urinary tract infection (UTI) and urinary incontinence, can be complex.

There are no universal diagnostic criteria for postpartum urinary retention (PUR).1 Therefore, institution-specific clinical guidelines vary greatly, and poor compliance with these guidelines adds complexity.3 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses estimate the incidence of PUR following vaginal delivery to be between 10–14%.1,4 The majority of PUR is covert or asymptomatic; there is spontaneous voiding but an unacceptably high post-void residual (PVR) volume. The remaining cases are overt urinary retention (there is no spontaneous voiding), with reporting at a lower rate of around 5%.1,5

The incidence of postpartum UTI, especially following catheterisation, is also unclear due to varying definitions of UTI (e.g., the data may include cases where a patient was treated for UTI, but not necessarily where there was a microbiological diagnosis) and selection bias in retrospective cohorts. The majority of postpartum UTIs are associated with intrapartum catheterisation, with incidences of 3.5–30% appearing in the literature, and no reduction in rates when intermittent catheterisation is used compared to continuous catheterisation.6,7

The incidence of urinary incontinence at three months postpartum, including all birth modes, is estimated to be approximately 30%.8 It is not possible to determine what percentage of bladder overstretch injuries from PUR contributes to this. Nor is it possible to determine rates of long-term sequelae (chronic retention, hypo-contractile bladder, incontinence and infection) in this population. Extrapolation from other populations and first principles indicates that the less severe the overstretch injury in magnitude, frequency and duration, the less likely are long term consequences.2 Stretch injuries of over 1,000 mL appear to carry these risks, with worse long-term voiding associated with larger volumes of retention and overstretch.

Junior doctors and hospital medical officers (HMOs) are usually at the front-line of responding to queries regarding bladder care in the postpartum patient, and for many of the reasons above, this can be a daunting task. The following scenarios drawn from real-life ward calls attempt to answer some practical questions that may arise.

Real-life scenario

Pager, 4:55PM: “Mrs U for d/c today, has failed TOV please review re need for IDC/home”

The Pandora’s box that is opened by a page like this at the end of the day can be overwhelming for a junior doctor, but hopefully these few practice points will assist.

Step one: Find your hospital’s policy on voiding after surgery or postpartum

Alternatively, the major centres all have policies that are readily available on the internet. These are safe and useful guides that can help to address hospital and patient pressure for discharge, and provide you with steps to take in managing a failed trial of void.10-14 There will always be a degree of variability between centres in relation to some of the specifics, so finding your local hospital policy can help to provide consistent advice.

Aspects that may differ between guidelines include:

- Percentage of bladder volume voided to be considered an adequate void (range 50–80%)

- Total volume voided to be considered adequate void (range 150–300 mL)

- Amount of residual volume considered to be an inadequate void (150–300 mL)

- Amount of time to allow following in-dwelling catheter (IDC) removal postpartum ability to void (range 2–6 hrs)13

- Duration of IDC re-insertion depending on residual volume

Step two: Determine the reason for catheterisation

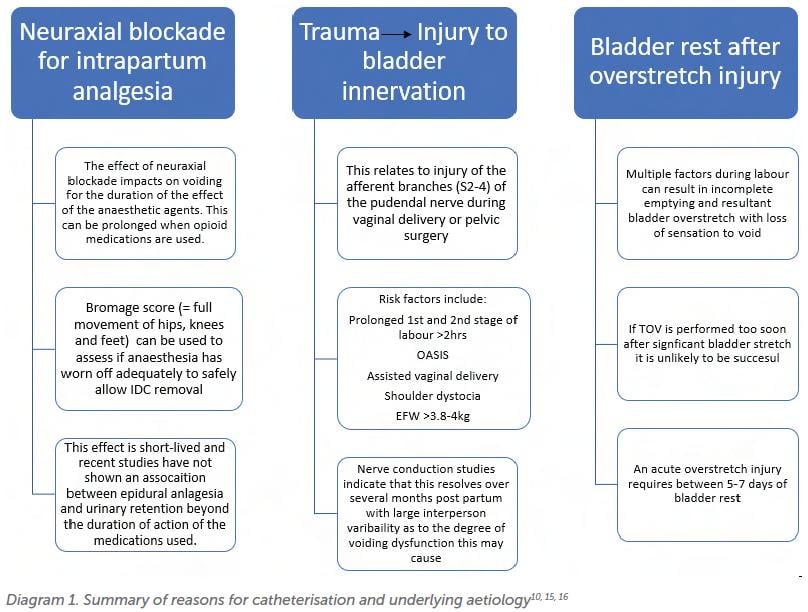

This can be important in terms of understanding the potential reasons for inability/ inadequacy of the void. The top three reasons and their relevant considerations are shown in Diagram 1.

If the patient has already had a catheter re-inserted after a failed trial of void 24–48hrs prior, most guidelines would recommend that further early attempts at voiding are not undertaken. The patient may be discharged with an IDC for 5–7 days before re-attempting a trial of void under supervision, or taught clean intermittent self-catheterisation (CISC).

Avoidance of IDC by teaching a patient CISC is an evolving area, with some studies showing promising results17. However, this needs to be considered carefully given the multiple complicating factors that may make timed voiding and self-catheterisation difficult for a new parent.

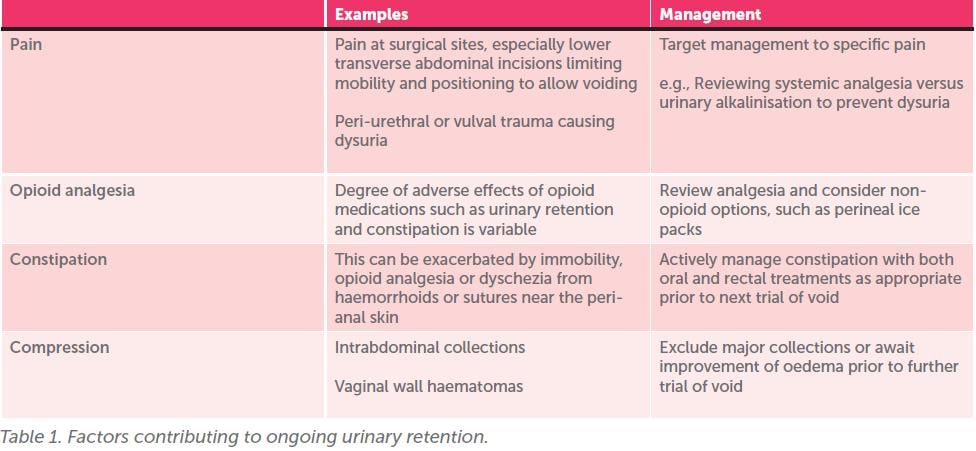

Step three: Modify any reversible causes that could be impacting on the patient’s ability to void

See Table 1 (next page) for a list of factors that can impair bladder function. By addressing these causes, it may be possible for patients to achieve a successful void preventing the need for IDC re-insertion when they undertake their next trial of void.

Note: It is important not to delay bladder emptying while attempting to modify the above, as this can result in bladder stretch injury, which will further compound urinary retention and voiding dysfunction.

Real-life scenario

The patient is worried about having a catheter reinserted if she fails her trial of void again. Can we just clamp the IDC and see if she has the urge to void?

The evidence would suggest that this process of clamping an IDC as a test of voiding urge is not effective. A Cochrane review determined that there was a greater incidence of UTIs, and delay to normal voiding in the clamp-and-release-group as opposed to the catheter removal group.18

Real-life scenario

The patient can void but has reduced sensation. What now?

First, exclude urinary retention. Check the patient’s trial of void (if they have completed one) and continue to record voided volumes and PVR volumes. Refer the patient for in-patient physiotherapy review, which may include behaviour modification and bladder training, as well as exercises to re-establish biofeedback and strengthen the pelvic floor.19 Bladder training includes timed voids, usually every four hours, to prevent the bladder from becoming overfilled, as well as a diary detailing fluid input and bladder outputs. Refer the patient to outpatient physiotherapy and/or a specialist continence nurse for post discharge follow-up.

Real-life scenario

Pager: “Patient for discharge with IDC? need for antibiotics”

Although an IDC duration of >24hrs is significantly associated with the development of bacteriuria, it remains unclear whether prophylactic antibiotics should be instituted as part of management for patients who require short-term IDC drainage.20 The benefit appears to be in a reduction in subsequent bacterial growth of catheter urine specimens, but few studies on this topic report on the main risks, which include adverse reactions to antibiotics and selection/ development of resistant bacterial strains and complicated infections.21

At present, Therapeutic Guidelines Australia recommends against antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent catheter-associated UTIs and often microbiology laboratories will not report bacteria detected from catheter urine specimens without

further information, given the bacterial colonisation rate of an IDC being 3–7% per day.20

To prevent catheter-associated infections:22

- Consider alternatives including CISC

- Ensure aseptic technique with insertion

- Review indication and duration of IDC before discharge

Real-life scenario

But how will I know if it is in fact a UTI if I cannot test a catheter urine specimen?

It remains important to diagnose true UTIs in the presence of an in-dwelling catheter, as persistence of true infection can result in delayed recovery of bladder functioning and systemic illness. Prior to urinary catheter re-insertion after failed trial of void, a UTI may be suspected based on symptoms of suprapubic pain, flank pain, fever or dysuria. If this is the case, the patient should be asked to provide a urine specimen, even if only a small amount is able to be voided.

If the patient cannot void at all, a ‘clean-catch’ specimen can be collected at the time of new catheter re-insertion and this can be sent for routine analysis.23 Alternatively, if further information is provided on the request form for a catheter specimen, this will aid in interpretation by the microbiologist to provide relevant results, rather than the specimen being rejected.

Conclusion

Postpartum bladder issues are common, and the diagnosis and management of these conditions are limited by our incomplete understanding on this topic. However, paying attention to specific risk factors associated with PUR, UTI and urinary incontinence, as well as careful history taking and examination, can empower clinicians (and especially junior doctors). Ultimately, this results in better care for the postpartum bladder and early identification of potential issues, allowing involvement of physiotherapy and continence nurses to aid in management.

Points to Remember

- Identify patients at risk of postpartum urinary retention and ensure a formal trial of void is undertaken postpartum or following IDC removal.

- Have a low threshold for assessing with a bladder scan or in-out catheter to determine post void residual (<150 mL is normal, as a general cut-off).

- Initiate management immediately to avoid repeating any overstretch injury once identified (volumes of ≥ 1000 mL with IDC insertion following inability to void).

References

- Yoshida A, Yoshida M, Kawajiri M, Takeishi Y, Nakamura Y, Yoshizawa T. Prevalence of urinary retention after vaginal delivery: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(12):3307-23.

- Madersbacher H, Cardozo L, Chapple C, Abrams P, Toozs-Hobson P, Young JS, et al. What are the causes and consequences of bladder overdistension? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(3):317-21.

- Lim JL. Post-partum voiding dysfunction and urinary retention. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(6):502-5.

- Kekre AN, Vijayanand S, Dasgupta R, Kekre N. Postpartum urinary retention after vaginal delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112(2):112-5.

- Cao D, Rao L, Yuan J, Zhang D, Lu B. Prevalence and risk factors of overt postpartum urinary retention among primiparous women after vaginal delivery: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2022;22(1):26.

- Gundersen TD, Krebs L, Loekkegaard ECL, Rasmussen SC, Glavind J, Clausen TD. Postpartum urinary tract infection by mode of delivery: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e018479.

- Evron S, Dimitrochenko V, Khazin V, Sherman A, Sadan O, Boaz M, et al. The effect of intermittent versus continuous bladder catheterization on labor duration and postpartum urinary retention and infection: a randomized trial. J Clin Anesth. 2008;20(8):567-72.

- Thom DH, Rortveit G. Prevalence of postpartum urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(12):1511-22.

- Mohr S, Raio L, Gobrecht-Keller U, Imboden S, Mueller MD, Kuhn A. Postpartum urinary retention: what are the sequelae? A long-term study and review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(6):1601-8.

Leave a Reply