The purpose of a pelvic floor examination is to make sense of the patient’s experience. It works symbiotically with the subjective assessment to better understand the structural and functional changes that might be contributing to symptoms. It is generally guided by the patient’s history, and so as not to require an entire book, a more general examination has been described below as a basic framework to direct appropriate interventions for diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, and the promotion of health.

Informed consent is a pre-requisite to any medical examination and although I will not detail this process here, I cannot overstate the importance of ensuring careful consideration for the psychological safety of the patient as well as the safety of the practitioner when doing pelvic floor examinations

A pelvic floor examination starts with a visual inspection of the vulva. It will often require gently parting the labia for a complete view; remember to clearly state what you are doing before you do it, as people feel before they hear.

Visual observation

Perineal skin assessment

Looking for presence of scars, lesions, fissures, trophic changes, color, erythema, swelling etc

Perineal body length

< or > 3cm. This a useful screen for OASIs risk in primiparous women between 35–37 weeks of pregnancy.1,2

Perineal body position at rest

Palpate the ischial tuberosities (IST) and assess the position of the perineal body in relationship to the IST. Ideally the perineal body is sitting at or just above the IST.

A descending perineum would sit below the IST at rest and suggests reduced pelvic floor support. An elevated perineum is significantly indrawn at rest, suggesting increased tone in the pelvic floor muscles.

Anal gaping

Non-coaptation of anal mucosa at rest.

This would suggest loss of normal anal sphincter resting pressure and has implications for anal control.

Visual observation continued

The next stage of visual observation involves assessing the dynamic function of pelvic floor muscle support, including contractile ability and distensibility.

Voluntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles

Ask the patient to contract the pelvic floor muscles (common cues: ‘squeeze and lift around your back passage like you are trying to stop wind’ or ‘squeeze and lift like you are stopping the flow of urine’). An ideal contraction will result in a ventral-cranial movement of the vulva, perineum, and anus; you might also notice closure of the urethral meatus and a clitoral nod.

If there is no movement this might indicate a motorcontrol issue, a very weak muscle or can suggest a high-tone muscle, especially if combined with a perineal body that is sitting high at rest. Descent of the perineum indicates an incorrect technique with overuse of the abdominal muscles which can contribute to incontinence and prolapse symptoms.

Relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles

Return of the perineum to its resting position. Observation of non-relaxing, partial, or delayed relaxation can indicate an overactive pelvic floor muscle which can contribute to symptoms such as pelvic pain, obstructed voiding or defecation symptoms and dyspareunia.

Perineal movement with bearing down/straining

Ask the patient to bear down/strain as if passing a bowel motion. A small amount (~1cm) of caudal descent of the perineum is expected. > 3cm of descent below the IST is considered excessive and will potentially contribute to obstructed defecation and prolapse symptoms. Cranial movement of the perineum suggests a dyssynergy and can cause symptoms of obstructed defecation.

Genital hiatus on straining/bearing down

Length from urethra to the perineal body on straining. This provides a useful measurement of pelvic organ support and risk of prolapse/ prolapse development.

The relative incidence of prolapse is nine times higher for women with Gh ≥ 3.5cm versus ≤ 2.5cm.3

Perineal movement with a cough

Observe perineal movement with a voluntary cough. Ideally the pelvic floor muscles pre-contract and there is minimal caudal descent.

If you notice caudal descent with a cough, ask the patient to contract their pelvic floor muscles and keep them contracted while coughing. This is called ‘the knack’ and has been shown to reduce leakage in around 80% of women with SUI.4

Prolapse assessment

A disassembled bivalve speculum or a tongue depressor covered in a glove is used to draw back the posterior or anterior vaginal wall during the examination. The patient needs to strain/bear down for 6–8 seconds.

The hymen is used as a reference point for quantifying the prolapse using the POP-Q system.

Stage 1: The most distal portion of the prolapse is more than 1cm above the hymen.

Stage 2: The most distal portion of the prolapse is between 1cm above and 1cm below the hymen.

Stage 3: The most distal portion of the prolapse is more than 1cm below the hymen but no further than 2cm less than the total vaginal length.

Stage 4: Represents complete procidentia or vault eversion.

Palpation

Note: the following describes assessing the pelvic floor muscles using a vaginal approach but when this is not indicated similar information can be gained from a rectal examination.

Sensation

A quick screen can just include light touch but if concerns assessment of sharp, blunt and temperature might be indicated.

Absence or altered sensation bilaterally/unilaterally suggest compromise in the s2–s4 nerve distribution.

Cotton swab test

A test for vestibular tissue sensitivity. The test is performed with a cotton swab, gentle pressure is applied around the vestibule in a clockface pattern.

The test is positive if gentle pressure reproduces pain. Often associated with superficial dyspareunia, difficulty with tampon insertion. Pain confined to the posterior vestibule suggests that a high-tone pelvic floor muscle is a major component.

Scar palpation

Palpate any scar tissue on the perineum and assess for tenderness/pain and tissue restriction.

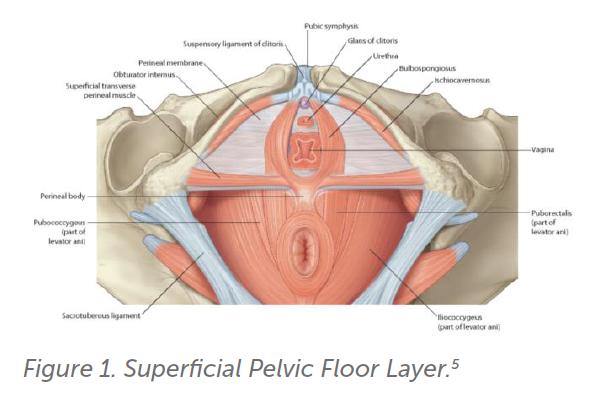

Superficial pelvic floor muscles (Bulbospongiosis)

This muscle is located at the entrance of the vagina. Place the palmer surface of the examining finger on the thickest portion of the muscle belly (4–5 o’clock, 7–8 o’clock; see Figure 1). Assess for tolerance to pressure, reproduction of symptoms, ability to contract, relax and flexibility.

Tenderness, pain or increased stiffness can potentially contribute to dyspareunia and the sensation of difficulty with penetration or tampon use. The pudendal nerve supplies the superficial pelvic floor muscles along with the external urethral and anal sphincter, an absent contraction can suggest potential compromise of the pudendal nerve. This has implications for bladder and bowel control.

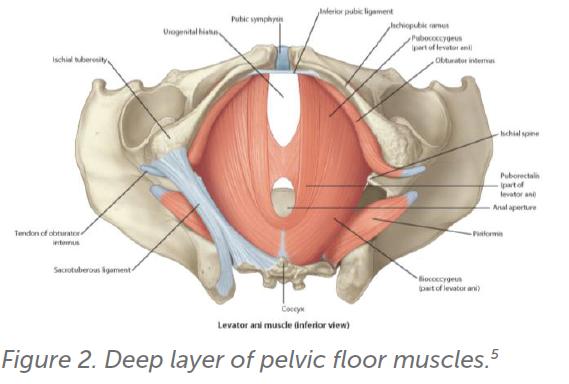

Deep pelvic floor muscles (levator ani)

The levator ani is palpated lateral to midline between 7 and 11 o’clock on the patients right hemipelvis and between 1 and 5 o’clock on the patients left. Insert the examining finger 1–2 knuckles (2–4cm) into the vagina (Figure 2). If the patient has pain symptoms, starting on the right side is recommended as the left is often more tender. Apply gentle pressure and assess for any tenderness or symptom reproduction. Tone can also be assessed by resistance to pressure. Assess quality of contraction and relaxation.

The muscles are considered impaired if palpation is painful, they cannot contract, or if they do not relax after a concentric contraction. Monitoring for accessory muscle use such as excessive abdominal wall contraction, adduction, posterior pelvic tilt, breath holding as this may indicate the need for physiotherapy input to optimise technique.

Obturator internus

The obturator internus is an external rotator of the hip. To find this muscle, place the index finger in the vagina to the depth roughly just past the second knuckle at 9–10oclock or 2–3oclock on the patients right or left side. Location accuracy can be confirmed by placing their external hand on the patient’s lateral knee and asking the patient to push their leg into this hand. This motion will result in the obturator internus contracting under the internal finger.

This muscle can cause referred pain at the ischial tuberosities, coccyx, buttocks, abdominal wall and contribute to symptoms of deep dyspareunia.

Levator ani avulsion

This can be assessed by placing the palmer aspect of examining finger between the side of the urethra and the levator ani insertion on the posterior pubic bone. Ask the patient to contract and you are feeling for the edge of the contractile tissue of the levator muscle. Ideally muscle bulk is felt on the side of the finger and equal on both sides.

Levator ani avulsion has implications for pelvic floor muscle strength and can predispose to prolapse symptoms and incontinence.

Assessment of strength

This can be done with a single digit or, in parous women with no pain symptoms, a second finger might be added. The patient is cued to contract their pelvic floor muscles and ideally a squeeze and lifting sensation is palpated. The simplest scale to use is the ICS scale (absent, weak, and moderate) but for a more qualitative scale the modified oxford scale is recommended).

Minimal or absent contraction in conjunction with increased muscle stiffness or pain can suggest a hightone muscle rather than a weak muscle.

Assessment of co-ordination

Ask the patient to cough and assess for precontraction of the pelvic floor muscles.

As stated previously, 80% of women with SUI showed a reduction in leakage by simply being taught ‘the knack’ (pre-contraction of the pelvic floor muscles before rises in intra-abdominal pressure such as cough).4

References

- Geller EJ, et al. Perineal body length as a risk factor for ultrasound-diagnosed anal sphincter tear at first delivery. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2014;25(5):631–6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2273-x.

- Lane TL, et al. Perineal body length and perineal lacerations during delivery in primigravid patients. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 2017;30(2):151–3. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2017.11929564.

- Handa VL, et al. Longitudinal changes in the genital hiatus preceding the development of pelvic organ prolapse. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2019;188(12):2196–2201. doi: 10.1093/ aje/kwz195.

- Miller JM, et al. Clarification and confirmation of the Knack maneuver: The effect of volitional pelvic floor muscle contraction to preempt expected stress incontinence’, International Urogynecology Journal. 2008;19(6):773–82. doi: 10.1007/ s00192-007-0525-3.

- Drake RL, et al. Gray’s Basic Anatomy. Third. Elsevier. 2021.

Leave a Reply