Worldwide, the rate of caesarean delivery is rising, with increasing scrutiny being applied to the indications for caesarean section (CS). Breech presentation is undoubtedly a significant contributor to CS rates, and affects three to four per cent of term pregnancies. Prior to the publication of the Term Breech Trial in 2000,1 breech presentation was not routinely considered to be an indication for caesarean delivery, although it was not uncommon, especially in developed countries. Hannah et al’s multicentre trial changed, perhaps irrevocably, the management of breech presentation at term and resulted in the loss of skills in vaginal breech delivery for a generation of trainee obstetricians.

The Term Breech Trial randomised 2088 women in 26 countries (both developed and developing) with frank or complete breech presentation to planned CS or planned vaginal breech birth. Trial recruitment was stopped early after interim statistical analysis showed significantly less perinatal and neonatal mortality and serious neonatal morbidity in the planned CS group than the planned vaginal breech birth group.

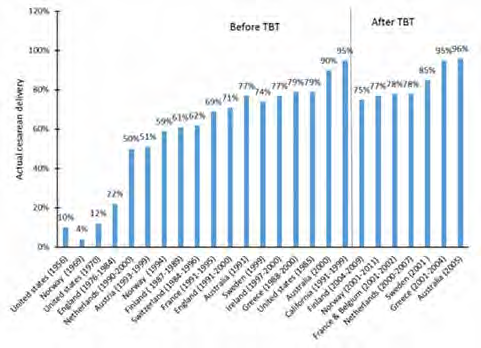

The trial had an almost immediate impact in many centres, with women counselled against vaginal breech birth due to the increased risk of perinatal and neonatal morbidity. Women were advised that planned CS was associated with a relative risk reduction of two-thirds compared to vaginal breech birth. In developed countries, CS rates for singleton breech presentation at term increased in the years following publication of the Term Breech Trial (Figure 1).2

Figure 1. The proportion of caesarean delivery in term singleton breech before and after the 2000 term breech trial (TBT) in selected developed countries.2

In a 2016 meta-analysis of planned vaginal breech birth versus planned CS at term,3 the authors concluded that vaginal breech birth carried a two- to five-fold higher risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity than planned CS (with an absolute risk of perinatal mortality of 0.3 per cent). They concluded that while the absolute risks of vaginal breech birth were relatively low, the decision regarding mode of delivery of a term breech presentation should be individualised.

In light of the increase in CS for breech presentation at term, there was renewed interest in external cephalic version (ECV) for management of breech presentation. RANZCOG recommends that women with a breech presentation fetus at or near term should be counselled about ECV and offered it if appropriate.4

Contraindications to external cephalic version include:

- Other reason to warrant CS

- Antepartum haemorrhage in the preceding seven days

- Abnormal CTG

- Major uterine anomaly

- Ruptured membranes

- Multiple pregnancy.

Caution should be exercised before offering external cephalic version in the following situations:

- SGA fetus with abnormal Dopplers

- Pre-eclampsia with proteinuria

- Oligohydramnios

- Major fetal anomalies

- Uterine scar

- Unstable lie.

The success rate of ECV at term is reported to be between 30 and 80 per cent. Many factors influence the likelihood of success, including experience of the practitioner, parity, liquor volume, uterine tone, engagement of the breech and palpability of the head and use of tocolysis. Tocolysis with salbutamol, terbutaline or nifedipine has been demonstrated to improve the success of ECV. If successful, less than five per cent of fetuses spontaneously revert to breech presentation. However, cephalic presentation following ECV may confer an increased risk of caesarean delivery compared with cephalic presentation alone.5

There have been some studies investigating ECV before term. A Cochrane review concluded that ECV performed between 34 and 35 weeks gestation may reduce the risk of non-cephalic presentation and vaginal breech birth, but may be associated with an increased risk of late preterm stillbirth, and advised that the option of preterm ECV should be carefully discussed with women to enable them to make an informed decision.6

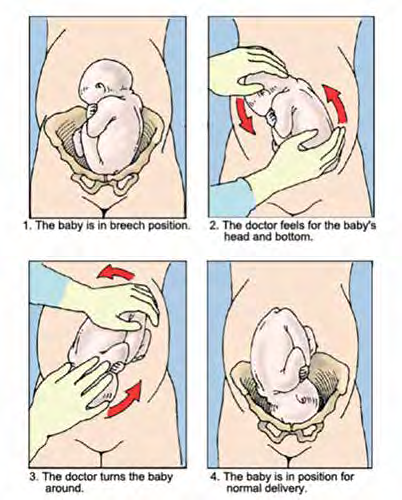

Various techniques have been described for performing ECV. Fetal presentation should be confirmed by ultrasound scan. It is recommended that ECV should only be performed in facilities with access to emergency CS delivery, and that tocolysis should be administered according to local institutional protocols. The woman should be positioned with a wedge under her right side to minimise aorto-caval compression. Powder or aqueous gel can be applied to the maternal abdomen to improve manipulation of the fetus through maternal skin. The breech should be disengaged from the pelvis prior to attempted clockwise or anti-clockwise rotation of the head and breech (Figure 2).7 Ausculation of the fetal heart +/- cardiotography (CTG) monitoring should be performed after ECV.

Figure 2. External cephalic version technique.

Complications from ECV are rare: less than one per cent. Reported adverse events following ECV include placental abruption, preterm labour, preterm prelabour rupture of membranes, cord prolapse, and fetal distress necessitating emergency CS.8 Ideally, breech presentation should be identified in the third trimester, prior to the onset of spontaneous labour. This allows time for appropriate discussion with the pregnant woman about options for management of breech presentation. ECV is not recommended once membranes have ruptured, and labour is not the ideal time for a discussion about vaginal breech birth versus CS.

After appropriate counselling, some women may opt for planned vaginal breech birth. This should take place in a facility with the availability of continuous fetal monitoring, immediate CS, and a suitably experienced obstetrician.9 Many practising obstetricians have limited experience with vaginal breech delivery, particularly in the term fetus. Maternity units should have agreed policies on intrapartum management of breech presentation.

Management of breech presentation at term is a challenge for obstetricians today. Careful interpretation of available evidence, appropriate discussion with pregnant women, and ready access to ECV and CS facilities are needed to provide best-practice care. While vaginal breech birth in selected situations is not associated with a significant increase in maternal or neonatal risk, the increase in CS rates for breech presentation has compromised the skill of obstetricians in vaginal breech delivery.

References

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, et al. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. 2000; 356:1375-1383.

- Berhan Y, Haileamlak A. The risks of planned vaginal breech delivery versus planned caesarean section for term breech birth:a meta-analysis including observational studies. BJOG. 2016; 123:49-57.

- Berhan Y, Haileamlak A. The risks of planned vaginal breech delivery versus planned caesarean section for term breech birth:a meta-analysis including observational studies. BJOG. 2016; 123:49-57.

- RANZCOG. Clinical Guideline on Management of breech presentation at term. Updated July 2016. Available from: www. ranzcog.edu.au/Statements-Guidelines/ Obstetrics/Breech-Presentation-at-Term,-Management-of-(C-Obs

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London (UK). Green-Top Guideline on External cephalic version and reducing the incidence of breech presentation. Guideline No. 20a. Reviewed 2010. Available from: www.rcog.org.uk/ en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/ gtg20a/.

- Hutton EK, Hofmeyr GJ, Dowswell T. External cephalic version for breech presentation before term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; Issue 7. Art, No.: CD000084.

- National Women’s Health. Turning Breech Babies or External Cephalic Version (ECV) [Patient information]. Auckland District Health Board; Feb 2015.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London (UK). Green-Top Guideline on External cephalic version and reducing the incidence of breech presentation. Guideline No. 20a. Reviewed 2010. Available from: www.rcog.org.uk/ en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/ gtg20a/.

- RANZCOG. Clinical Guideline on Management of breech presentation at term. Updated July 2016. Available from: www. ranzcog.edu.au/Statements-Guidelines/ Obstetrics/Breech-Presentation-at-Term,-Management-of-(C-Obs.

Leave a Reply