How should we interpret the evidence available for the use of transvaginal mesh in prolapse surgery?

About 20 years ago, many gynaecologists began to express disquiet about the long-term success of the conventional vaginal procedures performed for pelvic organ prolapse (POP), particularly for the long-term cure of cystocele. As dissatisfaction took hold towards the end of the 1990s, publications appeared that seemed to confirm what now seems set as a dogmatic assertion: all conventional vaginal surgeries for the correction of prolapse have unacceptably high failure rates.

At the same time, evidence from general surgery began to accumulate, indicating that hernia repairs could be made more durable by using artificial polypropylene mesh. That observation stimulated a new insight in gynaecologists: maybe a prolapse was just like a hernia. By this time, the evidence appeared overwhelming that new procedures were required to replace the seemingly dated and unsatisfactory vaginal repairs – and the key to increased durability would be polypropylene mesh.

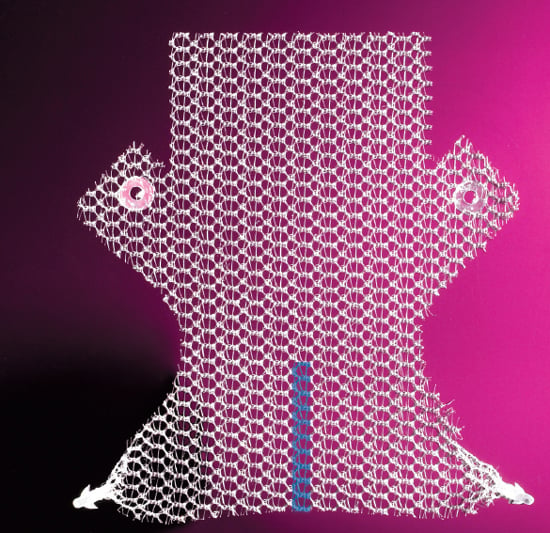

Initially different types of mesh were used, some good, some bad and some decidedly ugly. Accumulated experience with mesh revealed that lightweight monofilament polypropylene was superior to dense multi-filamentous materials, which tended to become encapsulated and not incorporated, thereby producing troublesome inflammatory reactions and rejection. Industry has been ingenious in the manufacture of new products and, today, there is a bewildering array of products to choose from.

Recently, however, dissenting ‘anti-mesh’ voices have become increasingly strident. Awareness has developed of some unique and potentially enduring complications associated with the use of vaginal mesh and authorities are re-evaluating the issues. Generalist gynaecologists watching these arguments develop would be forgiven if they were to cry despairingly, ‘A pox on bothyour houses!’ But, as a lesser poet than Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde, observed, ‘The truth is rarely pure and never simple.’

Some literature revisited

You may be familiar with the mantra that, ‘29 per cent of operations for vaginal prolapse fail and require further surgery.’ This figure comes from an article written by Ambre Olsen and her colleagues, published in 1997.1 This single article seems to be cited more often than any other in the world literature, or so it seems to me. This level of citation of a single 15-year-old publication must be remarkable. In all cases the Olsen article is used to illustrate the poor outcome of surgery for POP, quoting a reoperation rate of 29.2 per cent. I began to wonder about this figure and, a couple of years ago, decided to do something remarkable – I actually went back and read the paper!

The publication is a retrospective case note analysis of surgery performed for POP and/or urinary incontinence (UI) in the north west of the USA in a single year, 1995. They identified 384 cases where surgery had been performed for either POP or UI (and sometimes both). In 112 cases (29.2 per cent) this surgery occurred in someone who had a previous procedure for either POP or UI. Although this statistic is the origin of the oft-quoted reoperation figure, it is actually not possible to determine whether the reoperation was for UI or POP. And, if it was for POP, it is not possible to say whether they were same site recurrences or a different site. In subsequent interpretations, an assumption is made that if an anterior repair was performed it was for prolapse, but the authors clearly state that it may just as well have been for UI. In 212 cases the surgery was definitely for UI, since the procedures were either retropubic suspensions or needle suspensions. Thus, an indeterminate number of re-operations may have been undertaken for recurrent incontinence rather than recurrent prolapse. Why doesn’t anyone cite this article as an illustration of the failure rates of procedures for UI?

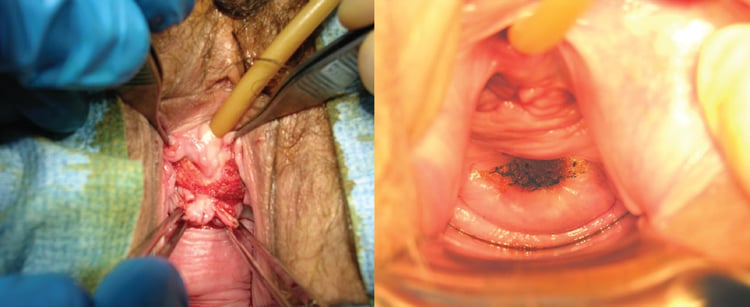

Exposure of the mesh through the vaginal wall can be a troublesome complication to manage.

The mean period from original surgery to the first repeat operation was 12.5 years, meaning that many of the repeat procedures were being performed in 1995 on women who had had their first operation in the early 1980s. A good deal changed in those years. I commenced my gynaecological training in the early 1980s and, by 1995, I did almost nothing the way I was originally taught.

I suspect that many subsequent authors who quote the Olsen citations have not read the original article carefully. The high reoperation rate fits perfectly with the prejudice that traditional vaginal surgery is lacking any long-term effectiveness and, perhaps, is even obsolete. These perceptions have driven the laparoscopic approach and the use of vaginal mesh. I am not suggesting for one second that conventional prolapse procedures do not have a failure rate, simply that it may be time to be a little more sophisticated about what is actually meant by ‘recurrence’ and ‘failure’. Many anatomical ‘recurrences’ may not even be symptomatic. In large population-based studies, some 20 per cent of older women have been found to have an asymptomatic POPQ grade two prolapse of one or other vaginal compartment.

The fundamental issue lies in the definition of ‘cure’ for prolapse. Unlike surgery for stress incontinence, outcome measures for prolapse surgery are poorly standardised. Most early studies relied upon anatomical descriptions: does an examining doctor think there is, or is not, a prolapse? More recently, subjective outcomes have been described: what does the woman feel is the outcome? On this basis, there is a clear discrepancy between what the woman says and what the examining doctor sees – there is a much lower ‘failure rate’ when we listen to the woman. If an endpoint, such as same-site reoperation rates, is measured, it gives a ‘failure rate’ of between five and ten per cent at one to five years after a conventional primary repair.2 3 4This sounds a bit better than 29 per cent, doesn’t it?

The problem of surgical morbidity

Say a new prolapse procedure is performed on 100 women and, postoperatively, five women are unable to have intercourse because of pain, but ten other women are able to recommence satisfactory intercourse now that they have no prolapse. So, more women are sexually active after the procedure than before. Is that a ‘good’ operation? Certainly not according to the five women with dyspareunia!

This introduces yet another variable: the perceived complexity, or simplicity, of the procedure we want to perform. This is an important concept in prolapse surgery. A conventional repair is considered technically straightforward, a mesh repair more challenging and an abdominal sacrocolpopexy perhaps most challenging. They all have different morbidity risks and the magnitudes of those risks are different. If a simple and safe surgical method of treatment wasn’t quite as ‘good’ at fixing the problem, how do we trade off the simplicity (and lack of patient morbidity) against the lesser effectiveness? What tools can be use to perform such a balancing act? How ‘less effective’ is it allowed to be before a technique is discredited and we say, ‘it’s not worth it’? Are there worse things following a pelvic floor repair than failure? And, if there are, exactly what are they? Even if the failure rate of conventional surgery is lower than previously suggested, what are we to suggest for those women who have recurrent prolapse? I would certainly miss the option of vaginal mesh in these cases.

A number of mesh solutions have been developed by industry. This is the anterior Elevate mesh from American Medical Systems.

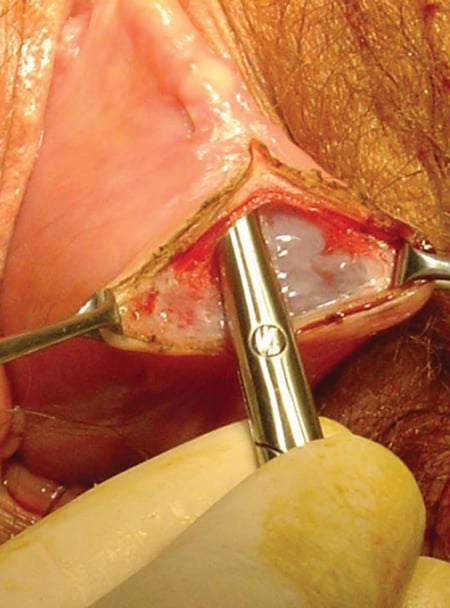

The clinical problem of severe prolapse poses major technical challenges; one of the suggested solutions is polypropylene mesh.

It is essential in vaginal wall dissection to get beneath the mucosal fascia. This runs the risk of inadvertent cystotomy.

Bad news from the FDA

Since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) report was released in 2011, many gynaecologists have become nervous about using transvaginal mesh in prolapse repairs. Perhaps this is not necessarily a bad thing. However, the FDA report created a strong impression that there had been an enormous number of serious unique complications reported with the use of vaginal mesh, and that these cases were just the tip of a looming iceberg. Using, what I consider to be, a selective reading of the literature, the FDA overtly declared there was no real evidence of the effectiveness of mesh when compared to more conventional surgical techniques. Recent figures suggest that as a consequence of this adverse report and concerns over litigation, the use of mesh in the USA has declined by 30–40 per cent. It should be placed on record that the Australian equivalent body, the TGA, has reported no similar increase in complaints about the use of vaginal mesh and the largest supplier of medico-legal services to our profession in Australia does not see vaginal mesh as a particular issue at this time.

The same FDA report lauded the effectiveness of mesh placed abdominally and suggested that the technique of abdominal sacrocolpopexy was the ‘gold standard’ of pelvic floor repair. The Australian newspaper quoted a gynaecologist talking about ‘cheese grater’ vaginas produced by mesh exposures, an alarmingly emotional response with no basis in fact and an unhelpful contribution to this important debate. So, what is the real situation?

The magnitude of the vaginal mesh ‘problem’

The FDA estimated that, in the three years covered by the report, a total of 225 000 vaginal mesh procedures were performed. There were 1503 reports of adverse events in the three years, which yields a rate of complication of 0.67 per cent, a fairly modest figure. (There were also 1371 adverse events reported with suburethral slings, but for some reason this did not produce any furore.) Despite this, the report implies that on the basis of these figures that the rates of complications are higher than conventional repair. Does anyone seriously think the rate of complications in standard repairs is less than one per cent?

All surgery involves risk. Mesh complications are being reported. No one is reporting much adverse data on conventional repairs (apart from ‘failures’). Quite simply, no one is looking.

Some assertions

- Mesh used in pelvic floor surgery introduces risks not present in non-mesh surgery for POP repair. These risks are said to be mesh erosion, pain, infection, bleeding, dyspareunia, organ perforation and urinary problems. These risks exist, of course, but with the exception of mesh erosion they also exist with traditional surgery. Furthermore, the risk of mesh erosion also exists with abdominally placed mesh.

- Mesh placed abdominally has lower rates of mesh erosion and has excellent durable success rates. The truth is that in reported series of vaginal and abdominal surgeries in experienced hands, erosion rates are actually pretty similar (3.3 per cent vaginal5 versus 4.3 per cent abdominal6). Even if it was true that mesh exposure rates are lower, they are not zero. As well, the material the mesh is made from is identical in both procedures. It is clear that, given the highly variable reported rates of mesh exposure in both vaginal and abdominal mesh, differences in surgical techniques most likely underlie the differing rates of mesh erosion. However, mesh erosions are not the only complication we should be concerned with when comparing abdominal and vaginal approaches to POP surgery. Significant gastrointestinal morbidity after sacrocolpopexy occurs in 20 per cent of patients. 7 The difficulty in assessing success rates is partly due, again, to the vagaries of how ‘success’ is measured after sacrocolpopexy. If you use descent of point C (the vault) as an endpoint, it has to descend almost the entire total vaginal length before it is accounted a failure: whereas the other points on the vaginal walls only have to descend 1cm or 2cm before they reach the hymenal ring (point 0 on the POPQ) and ‘fail’.

- Mesh shrinkage produces intractable pelvic pain at rest and pain with intercourse, which is impossible to treat. Many of us have heard terrible stories of distress and pain following vaginal mesh repairs. However, the reporting of a whole series of alarming complications referred to your practice is not a valid investigative tool. There are now a reasonable number of studies looking at postoperative pain, adverse mesh events and sexual functioning following vaginal mesh repairs.

One of the best randomised studies was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 by Altman and colleagues, a large multicentre study with many of the centres in provincial Scandinavia.8 It tells us much about what outcomes can be expected with the use of vaginal mesh in the widespread practice. This was a multicentre randomised trial of anterior Prolift™ mesh versus traditional anterior repair. Two hundred patients had the mesh and 189 had a standard repair and were followed up for one year. Multiple endpoints included quality of life (QoL) and sexual functioning. Cure of prolapse was defined anatomically and by a negative response to the question: ‘do you feel any vaginal bulge sensation?’ An intention to treat analysis was performed on those women who returned for follow up: 186 in the mesh and 182 in the traditional repair group.

‘Australia has been, and remains, at the forefront of research into these surgical technologies with many innovations arising from our shores.’

The mesh group had superior cure rates at one year: 60.8 per cent in the mesh group versus 34.5 per cent in the conventional group. Mesh surgery took longer (52.6 mins versus 32.5 mins) and caused more blood loss (84.7ml versus 32.5ml). Severe pelvic pain at two months was reported in five mesh cases (2.7 per cent) and in one anterior repair, but by 12 months only one case in the mesh group still reported pain (0.53 per cent).

De novo stress leakage is more common after mesh repairs and, by one year, five patients in the mesh group had undergone sling surgery. There were six subsequent procedures for mesh exposure (3.2 per cent) by one year. All were cured. Pain on intercourse‘usually’ was noted by 7.3 per cent of mesh group patients, and two per cent of the conventional repair patients. However, overall general satisfaction with sex was identical between the two groups (40 per cent). One patient underwent surgery for prolapse failure in the conventional group by one year.

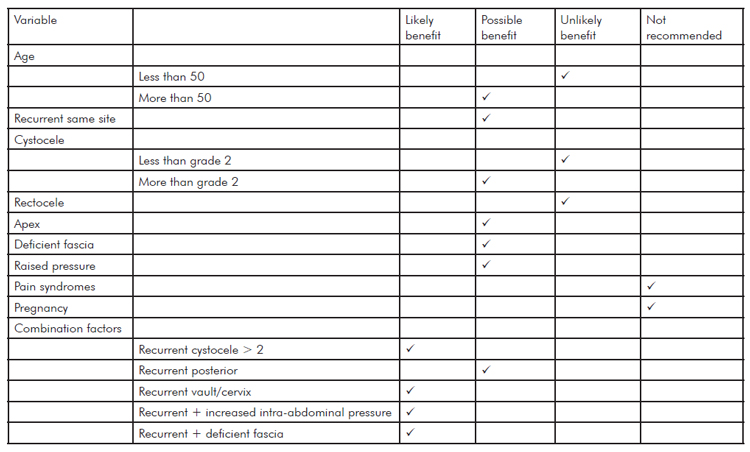

So, which patients should consider mesh?

This is not an easy question to answer since clear evidence is lacking and no guidance can be given regarding which mesh kit should be used since there is simply no robust comparative data available. A recent useful consensus statement has been published in the International Urogynaecology Journal9 and a summary of the recommendations is shown in the table. Primary prolapse, patients younger than 50, lesser grades of prolapse and posterior compartment prolapse without apical descent are unlikely to benefit from mesh.

Evidence and risk

No surgical procedure is without risk. But what is an ‘acceptable’ risk and what is an ‘unacceptable’ risk? This is a critical topic and goes to the heart of this discussion. Everything comes at a price. In Australia, we can all strongly support the FDA recommendations for patients to engage in a dialogue with the treating surgeon regarding the use of mesh and be fully informed regarding the potential benefits and hazards of such surgery. But, where possible, the magnitude of these risks should be based upon data. While the data are not complete, it is mischievous to imply they do not exist.

Australia has been, and remains, at the forefront of research into these surgical technologies with many innovations arising from our shores. RANZCOG has the oldest formal training program in the world devoted to the management of POP, ensuring a well informed and highly skilled workforce of subspecialists in this areafor the last two decades. The incidence of complications when using artificial mesh in prolapse surgery is likely to be related to surgical expertise, training and work volume as well as the adequacy of the patient-selection process. The most important fact remains that surgeons who use mesh infrequently in improperly selected cases will get higher rates of complications. This is what the evidence tells us.

Declaration of interest

Malcolm Frazer holds contracts as a preceptor for Johnson & Johnson Gynecare as well as American Medical Systems mesh products for which he receives a fee. He has received financial support from both organisations to attend scientific conferences as an invited lecturer.

Table 1. Potential benefits of polypropylene mesh use for vaginal prolapse (adapted from10).

References

- Olson AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 1997; 89: 501-6.

- Hawkins E, Rajkumar S, Masood M. Long term satisfaction with prolapse surgery in general gynaecology. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008; 19: 1441-1448.

- Miedel A, Tegerstadt G, Morlin B, Hammarstom M. A 5-year prospective follow-up study of vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008; 19: 1593-1601.

- Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, et al. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113: 367-373.

- Altman D, et al. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1826-36.

- Brubaker et al Two year outcomes after sacrocolpopexy with and without Burch to prevent stress incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112(1):49-55.

- Whitehead WE et al. Gastrointestinal complications following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197:78.

- Altman D, et al. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1826-36.

- Davila W, Baessler K, Cosson M, Cardozo L. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2012 published online 7 March 2012.

- Davila W, Baessler K, Cosson M, Cardozo L. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2012 published online 7 March 2012.

Leave a Reply