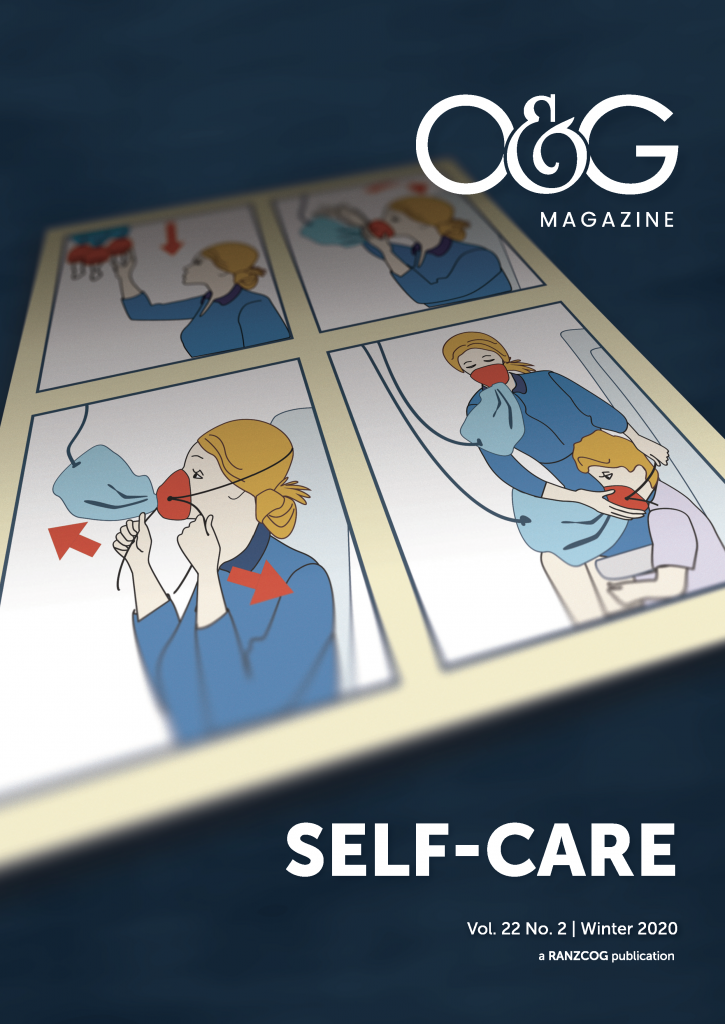

The theme of this issue of O&G Magazine is Self-Care, or how to manage the stresses inherent in our speciality. Be it physical, mental, emotional, administrative; how to deal with adverse outcomes, the unpredictability of clinical care, effect on relationships outside work. We all know that prevention is better than cure, so in this article I wish to discuss ways of organising the ‘work’ part of the so-called work-life balance to avoid some of these problems in private practice.

Full disclosure: as well as a past life as an academic, and still doing public work, I am part of a group private O&G practice that has been evolving over 22 years and is still working well. Here I hope to explain some of the good and bad things we have found over this time and also describe other models of practice that may suite different situations.

Where to after gaining fellowship?

According to the College-wide annual survey, 65% of Fellows provide care to private patients, possibly a higher proportion in Australia compared to New Zealand. For those who choose this path, moving from the relatively predictable structure of a training position, with its set hours, hierarchical structure and strict practice guidelines brings with it a new set of problems.

The traditional model of solo private practice involves setting up rooms, employing staff, finding a referral base, gaining accreditation and admitting rights to private hospitals, understanding financial and regulatory issues and deciding what and how to charge for your services. It also means being responsible for your patients’ obstetric (or gynaecological) care continuously, unless adequately handing over to a trusted colleague. In reality, this means you can never be more that 20 mins away from the hospital, always sober and never in total charge of children you can’t leave.

This model of practice therefore requires commitment, not only from the obstetrician but from family members. In order to manage some of these issues, various alternative models of practice have been tried, as mentioned below. These options are not exhaustive, and hopefully more ideas will be explored as younger Fellows think more laterally about how they want to pursue their careers.

The traditional weekend cover

The commonest way to have time off is to be part of an on-call sharing group, especially for weekend or holiday cover. Individual practitioners form a group of several doctors who take responsibility for the practices of colleagues in a regular roster, so one may be on call one in three, four, five or more weekends, thus covering a multiple number of patients in turn. This may mean being very busy when ‘on’ but then having several weekends off as compensation. Sometimes these arrangements cover weeknights as well, especially for special events (family or school reasons), or perhaps to recover from a bad run of nights on. Major issues with this model are adequacy of handover, patients’ expectations if cared for by a stranger and renumeration between doctors.

Group practice

General practitioners are often organised in groups, perhaps now run by bigger corporate entities, and certain other specialities (such as radiologists, gastroenterologists, dentists) work as groups. Such a model was attempted in Melbourne some years ago where a company built a stand-alone private O&G hospital, then looked for specialists to be employed to care for the hospital’s patients. I call this the ‘if you build it, they will come’, or the ‘top-down’ business model. It failed, I believe, as it was planned from a business perspective, not from the angle of practising obstetrics in a sustainable manner.

Perhaps one reason for this failure is the particular relationship obstetricians (as opposed to other specialists) have with their patients. We are generally looking after a healthy woman, usually part of a family, for an extended period with a condition that is not necessarily pathological, but carries risk and uncertainty (and has more lay opinion than any other area of medicine.) When women are paying for private care, they often expect to build a relationship with their care givers. Managing patient expectations with good explanations and education about the benefits of shared cover is a major part of group practice. Here the ‘pilot analogy’ works well; explaining that pilots must have clear times off to recover so as to be ready for unexpected emergencies, much like obstetricians.

One way to go

Our practice, based in a major capital city, began after soul searching as registrars watching how our senior colleagues and mentors ran their lives. At that time, there were far fewer women doing O&G and we started to look at alternative ways of practising that would allow us regular time off. This took over two years of research, contacting groups in the US, doing a TAFE business course and getting expert financial and tax advice. In the beginning, this was not without challenges and over the years we have tried different ideas, mainly in terms of the on-call roster and ways of billing and paying each other for work done, especially when the members have taken on different workloads and patient numbers, often due to family commitments. We have heard registrars talking about going into group practice now as if it is just another job to apply for, without realising the subtleties of how to share, both clinically and in a business sense. Unfortunately, some groups have floundered if these issues are not clear cut from the beginning.

Our model now has five obstetricians (from the original three, then four), who all do variable amounts of private gynaecology depending on skills and interests. All are RANZCOG training supervisors and do public clinics and on call. Our rooms are onsite where a private hospital is co-located with a tertiary public hospital, which allows us to look after very preterm or high-risk pregnancies. Our on-call roster is planned 18 months in advance, with one of us being nominally responsible for the whole group’s patients for 24–48 hours at a time. In reality, we look after our own patients during week days, and plan elective deliveries accordingly, but have the option of a day off, or to handover for the evening and night if we need or want to. We share a suite of rooms and employ three midwives who help with procedures, answer patient enquiries, do CTGs, patient education and occasional routine antenatal care. We are sole traders, but have a Unit Trust running the business and employing several part-time reception staff and a practice manager, and each doctor has a service agreement with the Trust. We share operating lists and assist each other in hours if possible. Our patients are informed of the group system via our website, verbally when they book and receive a detailed email within 24 hours explaining the practice model and its benefits, both to doctors and patients. Our patients book in the name of their primary obstetrician, but meet each of the others at some stage in their antenatal course and we deliver 60–75% of our own patients.

Alternative structures

Other practices have a more strict ‘on-call’ roster where one doctor looks after all the practice patients for labour and emergencies for a day, and antenatal visits are booked as a clinic where a doctor (or midwife) sees all women who want to come on that day. Many practices now include midwives using their particular skills to enhance the experience of private patients; doing education, lactation support, assessing perinatal mental health, postnatal care (even home visits). Some practises are now including midwife care and private delivery (with obstetrician back-up) for a lower cost model.

I believe some of the more intangible benefits of group practice are its strengths as listed below, not just the obvious time on- and off-call.

Benefits of group practice

- shared costs of running a practice, ability to afford equipment early on (ultrasound, colposcope, steriliser)

- colleagues around to assist, provide advice, backup for family or health emergencies

- multiple opinions for each patient

- shared business responsibilities, employer issues, compliance

- the benefits of having members at different ages and life stages means that there is a range of experience and expertise, and the ability to arrange maternity leave, leave in or away from school holidays, flexibility to change on-call at short notice when child free

Downsides of group practice

- less clinical autonomy, need to have similar philosophy and management principles

- need to compromise on many issues, from décor to financial and clinical decisions

- missing the absolute relationship with a patient

- need for good handover (easier these days with digital options)

- managing some patients’ disappointment

Ten issues to consider in group practice

- Choose personalities that suit, not just bodies to cover the hours. This is one of the main reasons why some groups fail

- Good communication – sort out issues internally, avoid lack of cohesion apparent to colleagues (corridor gossip), like with any long-term relationship, don’t let things fester, be ready to compromise

- Agree how decisions will be made and how to manage conflict (consensus, voting)

- Get good financial advice about structure of the business; accountability, avoiding collusion, paying each other

- Decide how patients are accepted into the practice, individual referrals or equal numbers for each practitioner or book to the practice alone

- Role of midwives: independent practitioners, employees

- Plan how and when to handover labouring women, what’s best emotionally and clinically, not just deciding who charges for the delivery (for example, handover in early labour rather than when awkward decisions may need to be made at full dilatation)

- Consider a business ‘pre-nup’ covering all possibilities: a doctor leaving, becoming incapacitated, de-registered, wanting to decrease hours or take more or fewer patients, provisions for extended leave (maternity, long service, sick), how many weeks of holiday each

- The use of locums for extended leave

- How someone joins or leaves the practice (buy in/out)

A good way to test out a new member is for them to cover each doctor in turn, for two to three months, thus allowing extended leave for members and the ability to see if someone new is the right fit for the practice. This is also a good way for new Fellows to gain experience of private work without expensive outlays. Often at this stage of their career, they have the generalisable skills to cover a consultant’s public and private commitments, thus allowing someone to have a complete break. Remember, there needs to be a long lead time to plan extended holidays in order to warn patients as they book, so plan to offer services for one to two years hence.

If real estate is about position, position, position, then group practice is about personality, communication and compromise. The above ideas are not exhaustive. New arrangements with private hospitals and midwives may be the way forward with a range of billing options for patients of different risk, wants or needs. Group practice may also allow variable workloads for different stages of a career, and thus ease one into retirement. In the end, the best things about a group practice are the support, camaraderie, clinical backup and planned time off, which avoids burnout and leads to a long-term sustainable career.

Leave a Reply