Little did we know when the idea of Self-care was suggested as a theme for O&G Magazine, that we would be compiling the articles in a time of self quarantine, social distancing and drastically reduced routine medical services due to an international health crisis! One definition of self care is ‘the practice of taking an active role in protecting one’s own wellbeing and happiness, particularly in times of stress,’ and this seems particularly appropriate right now.

As I write this, we seem to be over the first wave of COVID-19 panic. The curve is flattening, and there is talk about relaxing restrictions and even potential local eradication of the virus in Australia and New Zealand. Hopefully with early trials of treatments and multiple centres developing a vaccine, we will not face a global ‘relapse’ and many of those newly acquired ventilators will stay wrapped in plastic.

One noticeable effect of the current pandemic is learning how we as a society, and as individuals, deal with such widespread disruption to routine life and work. The media have been full of ways to maintain sanity while either working (and often schooling) from home, working and placing oneself at risk, or dealing with unemployment or loss of business income. As health professionals, we are lauded for being on the frontline, particularly in obstetrics as this is one area that can’t be put on hold. In our speciality of O&G, we are often confronted with changing situations requiring urgent decisions, but usually still within our sphere of influence and expertise. Now we have had to face the possibility of a potentially personally risky working environment on top of the usual uncertainties of our daily clinical lives. Health workers are on the frontline of exposure and we know that many of us may get the virus (and hopefully recover) but in the meantime may put our families or other contacts at risk.

The way we respond to such stress says something about our innate personalities: is the glass half full, half empty or just at 50%? Do we respond with anxiety and become overcautious, or play down the risk and cut corners with a degree of fatalism? Coping with post-Covid life will be played out on the background of all the other stressors innate in our profession.

Doctor’s are known for neglecting their own physical health and are notorious for ignoring mental health issues. This was examined two years ago in our O&G Magazine issue on ‘Mind Matters’ (Spring 2018). Specialists in particular are not good at having their own GP. Suicide is the leading cause of death for men aged 15–44, and female doctors kill themselves at three times the rate of other employed women. For every death by this cause, there are thirty attempts. This has been publicly discussed following our Past President’s telling of his own story as an at-risk young doctor and how friends at the time intervened to offer salvation.

In the recent US Specialists and Burnout Survey 2020, 46% of the 600 O&Gs answered that they felt burnt out. This being described as ‘a long-term, unresolvable, job-related stress that leads to exhaustion, cynicism, feelings of detachment from one’s job, responsibilities and lack of a sense of personal accomplishment.’ Interestingly, each age group highlighted different concerns. Of the total 15,000 specialists, the Gen X’s (age 40–54) were most burnt out. Forty-eight percent described themselves as suffering this with their main issue being lack of respect. These doctors are also in the band of the ‘sandwich generation’, who are mid-career, at their busiest professionally and often juggling multiple roles outside work. Of the Boomers (age 55–73), 39% were burnt out and were most frustrated with computerisation, and of the Millennials (age 25–39), 38% were already burnt out due to too many hours at work.

There is a risk of confusing burnout with major depression, and as doctors we are taught not to show emotion or ask for help. We may end up suffering from compassion fatigue and seeing patients as a chore. As an obstetrician, I still get a buzz from delivering a healthy, screaming baby to besotted parents and believe that when I lose that feeling, its time to reconsider my priorities.

While we acknowledge these issues at an academic level, many of us will not face them personally or don’t know how to raise them with at-risk colleagues. The following articles will hopefully cover a range of practical ideas to help us identify and cope with some of the stresses inherent in our speciality. There are issues specific to certain ages and career stages, practical tips about work practices and organisational strategies, and contacts for resources available within RANZCOG and in other domains. As one of our authors writes, ‘It’s okay to not be okay’. Not every article will resonate with each reader, but hopefully the information and suggestions described will be available as useful resources when required.

So what can we learn from the current situation? Forced social and workplace changes happening quickly may drive innovation. We may have to evaluate how and why we work, how we manage Self-care, and care of our patients and colleagues. We may become more agile in practice, with Telehealth and Zoom meetings having an ongoing role, and some of us will cope better than others with change and uncertainty.

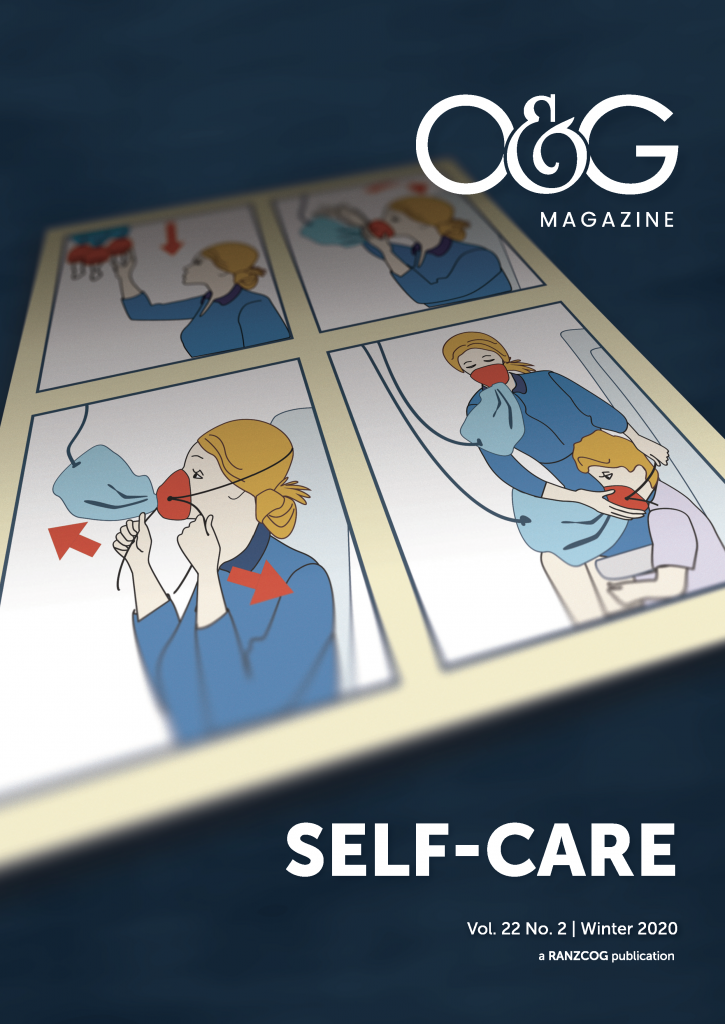

When looking for a pithy quote to end this piece, I found many somewhat stomach-churning, fluffy ideas about self-love, full of sunsets and kittens. However, the underlying message of many was that we can’t look after our patients if we are impaired ourselves. So, in this time of donning and doffing PPE practice, I think we should again look to the airline industry for safety protocols and follow the familiar advice to ‘Put your own oxygen mask on first.’

Leave a Reply