Progesterone: the pregnancy hormone

Progesterone is the hormone produced by the corpus luteum (the remnants of the ovarian follicle that enclosed a developing ovum). It is essential, as it prepares the tissue lining of the womb (endometrium) for embryo implantation. Progesterone is also necessary, as it supports the subsequent development of a pregnancy beyond implantation 2. The syncytiotrophoblast (a specialised layer of cells in the developing placenta) secretes human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) which is responsible for stimulating ongoing progesterone release from the corpus luteum. The placenta then becomes the dominant source of progesterone after its development from eight to 12 weeks gestation 3,4.

This hormone decreases uterine muscle contractions (contractility of the uterine myometrium) and is also thought to provide an immunomodulatory effect at the interface between the interface of the outer layer of the embryo and the uterine lining during pregnancy (the trophoblast-decidua interface). It is proposed that these combined effects may help lower the risk of miscarriage 3,5.

Progesterone has also been shown to reduce the risk of preterm birth in women with an identified short cervix on mid-trimester ultrasound, or women with a history of previous spontaneous preterm birth 6. While progesterone levels are used to assess a woman’s luteal phase without pregnancy, they are not reliable in defining the fertile level of luteal function. They are also not shown to assess the likelihood of miscarriage or the benefit of administering progesterone in preventing miscarriage 2.

The Epidemiology and Pathology of Miscarriage (Threatened & Recurrent)

Miscarriage, defined as the loss of pregnancy before 20 weeks gestation1, carries both physical and emotional risks. In addition to the immediate physical risks of bleeding, infection and potential surgical complications, miscarriage can also result in profound psychological distress for families, increasing the risk of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide 1.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 15-25% of all pregnancies 7. Most cases are considered sporadic, and a result of random chromosomal abnormalities. Recurrent miscarriage is defined as three or more miscarriages (both consecutive and non-consecutive) in the first trimester. Recurrent miscarriage affects 1% of pregnant women—a rate significantly higher than would be expected by chance alone 0.4% 8,9. Notably, 50% of all recurrent miscarriages have no identifiable cause 3. Evaluation is warranted after two first-trimester miscarriages if there is clinical suspicion that they are not merely sporadic in nature 10.

Threatened miscarriage, characterised by vaginal bleeding with a closed cervix in early pregnancy, affects 20–25% of pregnant women 5. Bleeding in early pregnancy has been associated with complications later in pregnancy, such as antepartum haemorrhage (APH), preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPROM), preterm delivery, and fetal growth restriction 3.

Multiple medical, anatomical and lifestyle factors influence the risk of miscarriage. Conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, antiphospholipid syndrome, and acquired or inherited thrombophilia should be investigated in women experiencing recurrent miscarriage. Lifestyle factors include body-mass index (a very low or high BMI), smoking, and alcohol and caffeine consumption.

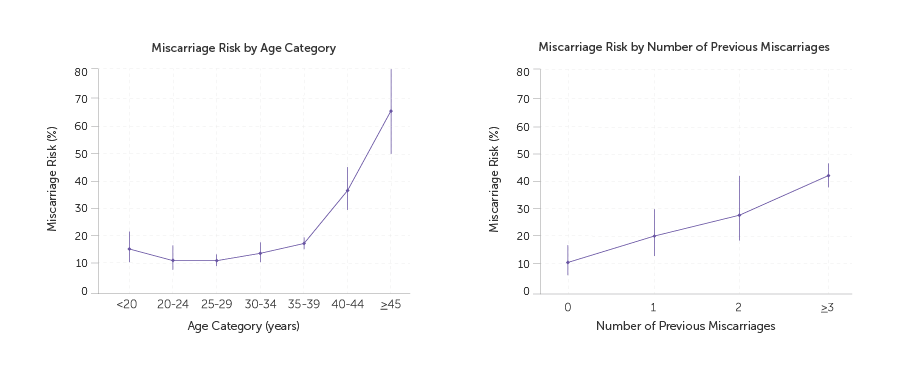

Maternal age and previous miscarriages significantly increase the likelihood of subsequent pregnancy loss. In Australia, the average maternal age has risen from 30.0 years in 2010 to 31.2 years in 2022, with 27.1% of mothers aged 35 or older 11 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Miscarriage risk by age category and number of previous pregnancies 1 Source: Quenby et al. Miscarriage matters: the epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss published in The Lancet.

The Use of Progesterone in Early Pregnancy

Research into progesterone supplementation for preventing miscarriage has produced mixed results. The PROMISE (PROgesterone in recurrent MIScarriagE) trial, conducted in the UK and Netherlands and published in 2015, found that first trimester progesterone therapy in women with a history of unexplained recurrent miscarriages (three or more) provided non-statistically significant benefit in achieving higher live birth rates 3.

The PRISM (PRogesterone In Spontaneous Miscarriage) trial was a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial of progesterone in women with early pregnancy vaginal bleeding 4. It found significant effect of progesterone treatment on live birth rates in a specific group of women – those who had experienced three or more previous miscarriages.

The incidence of live births in women who had no previous miscarriage was 74% in the progesterone group and 75% in the placebo group (RR 0.99 95% CI, 0.95 to 1.04); the incidence among women who had one or two previous miscarriages was 76% and 72% (RR 1.05; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.12), respectively; and the incidence among women who had three or more previous miscarriages was 72% and 57% (relative rate, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.51) (P = 0.007), respectively, reflecting a significant benefit.

Additionally, there was no significant difference between the progesterone and placebo groups (about 5%) in the occurrence of serious maternal or neonatal adverse events including pre-eclampsia, preterm prelabour rupture of membranes, postpartum haemorrhage, cervical cerclage, intrauterine growth restriction, and many others4. Importantly, the proportion of neonatal congenital abnormalities was also equivalent at 3.4% in each group 4.

The dose used in both the PROMISE and PRISM trials was 400mg of micronised progesterone administered twice daily as a pessary, until a gestation of 12 and 16 weeks respectively. It is not yet clear which formulations, routes and timings of administering progesterone may yield the best outcomes, and whether these factors may affect the outcomes of asymptomatic women and those with unexplained recurrent miscarriage. However, the use of a pessary is supported by the immunomodulatory effects of progesterone at the trophoblastic-decidual interface, as it allows for a “first uterine pass” effect, delivering the medication directly to the uterus. Additionally, due to the production of progesterone by the placenta from 12 weeks, progesterone pessaries are thought to offer limited benefit beyond the first trimester, as evidenced by the very low proportion of miscarriages beyond that time.

Institutional Recommendations and Considerations for Practice

Based on this information, the guideline from the United Kingdom (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists,2023) suggests consideration of progestogen supplementation in women with recurrent miscarriage who present with bleeding in the first trimester (400mg micronised vaginal progesterone twice daily at the time of bleeding until 16 weeks gestation). The guidelines also recommend that women with unexplained recurrent miscarriage should be offered supportive care, ideally in the setting of a dedicated recurrent miscarriage clinic 10. The RANZCOG statement also acknowledges progesterone supplementation until the second trimester in women with threatened miscarriage but does not recommend it for recurrent spontaneous miscarriage 12.

Conclusion

Progesterone is a vital hormone for pregnancy. Evidence from high quality randomised trials have shown that administering a dose of 400mg micronized progesterone vaginally BD (twice daily) in early pregnancy is safe for both mother and fetus, with no increase adverse effects. The most significant benefit is observed in women with early pregnancy bleeding who have experienced three or more previous miscarriages.

References

- Quenby S, Gallos ID, Dhillon-Smith RK, Podesek M, Stephenson MD, Fisher J. Miscarriage matters: the epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. Lancet. 2021 May 1;397(10285):1658-1667.

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Diagnosis and treatment of luteal phase deficiency: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2021 Jun;115(6):1375-1383.

- Coomarasamy A, Williams H, Truchanowicz E, Seed PT, Small R, Quenby S, et al. PROMISE: first-trimester progesterone therapy in women with a history of unexplained recurrent miscarriages – a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, international multicentre trial and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(41):1-152.

- Coomarasamy A, Devall AJ, Cheed V, Harb H, Middleton LJ, Gallos ID. A randomized trial of progesterone in women with bleeding in early pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1815-1824.

- Zhao Y, D’Souza R, Gao Y, et al. Progestogens in women with threatened miscarriage or recurrent miscarriage: A meta-analysis. Acta Obstet GynecolScand. 2024;103:1689-1701.

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Progesterone use in the second and third trimester of pregnancy for the prevention of preterm birth. Melbourne: RANZCOG; 2022.

- Hure AJ, Powers JR, Mishra GD, Herbert DL, Byles JE, Loxton D. Miscarriage, preterm delivery, and stillbirth: large variations in rates within a cohort of Australian women. PLoS One. 2012;7(5).

- Saccone G, Schoen C, Franasiak JM, Scott RT Jr, Berghella V. Supplementation with progestogens in the first trimester of pregnancy to prevent miscarriage in women with unexplained recurrent miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Fertil Steril. 2017 Feb;107(2):430-438.e3.

- Li YH, Marren A. Recurrent pregnancy loss: A summary of international evidence-based guidelines and practice. Aust J Gen Pract. 2018 Jul;47(7):439-444.

- Regan L, Rai R, Saravelos S,Li T-C, on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Recurrent Miscarriage: Green-top Guideline No. 17. BJOG. 2023;130(12):e9–e39.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australia’s mothers and babies. Maternal age. Last updated 24 Sep 2024. Available from: aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/australias-mothers-babies/contents/overview-and-demographics/maternal-age

- RANZCOG. Progesterone support of the luteal phase and in the first trimester. Melbourne: Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; March 2018.

Leave a Reply