In 1877, a 29-year-old woman named Annie Besant stood before an all-male jury in the High Court of Justice in London and spoke out in favour of birth control. She was the first woman to publicly endorse birth control and the right of women to choose when, and if, they had children. But how did this come about? And why was she facing the highest court in the land? The answer lies within a booklet titled Fruits of Philosophy.

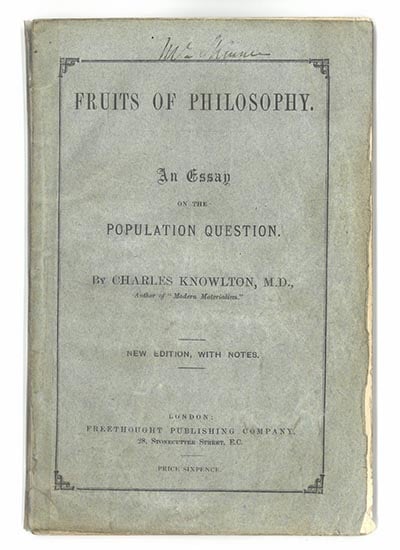

Written in 1832 by American doctor Charles Knowlton to inform his patients about contraception and sex education, the booklet was originally published anonymously due to laws in the United States which prohibited the publishing of immoral and obscene material, which included information about contraception.1

The initial printed form of the booklet was very small, measuring about three by two and a half inches, allowing it to be easily hidden by, and distributed to, anyone seeking knowledge about contraception. Despite originally being published anonymously, Knowlton’s name was nonetheless quickly attached to the publication. Due to his efforts to repeatedly publish the book, Knowlton was prosecuted for obscenity three times between 1832 and 1834, once drawing a three-month jail term in Cambridge, Massachusetts.2 Cooperwood and Hawley have termed Knowlton’s actions in publishing and circulating this booklet as one of “the more subtle strategies of resistance in early American history.” 3

In London, Fruits of Philosophy had been in circulation since 1833, but became the subject of controversy in 1876 when a “disreputable Bristol bookseller” named Henry Cook “put some copies on sale to which he added some improper pictures.” Cook was prosecuted for this, pled guilty, and Fruits of Philosophy was subsequently banned in Britain under the Obscene Publications Act of 1857.5

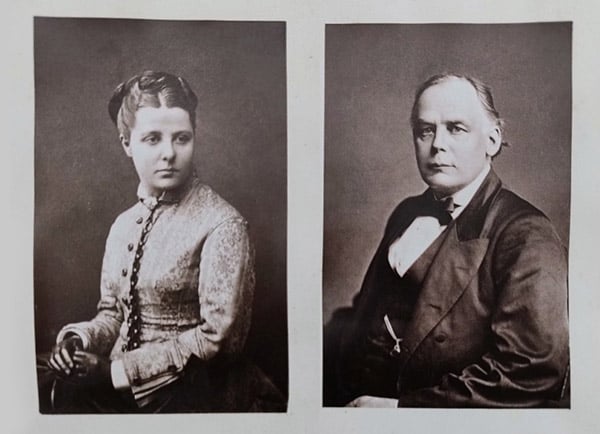

Besant was relatively unknown as a public figure at this time, but that was soon to change. In 1874, Annie Besant had met celebrated atheist Charles Bradlaugh, an event which Besant states “coloured all my succeeding life.” 4 Bradlaugh was the leading personality in the nation’s secularist movement, and the two formed a lifelong connection which burst into life when they joined forces in 1877 to challenge the Fruits of Philosophy ban.

Bradlaugh and Besant saw the ban as a legal restriction on the freedom to distribute birth control information 5 and were determined to act. They decided to publish the booklet themselves, “to test the right of discussion on the population question.” 4 As Besant recounts, they “took a little shop, printed the pamphlet, and sent a notice to the police that we would commence the sale at a certain day and hour, and ourselves sell the pamphlet, so that no one else might be endangered by the action.” 4 Having publicly announced their intent, “a crowd filled the space outside the publishing house” the following day, and the pair “sold hundreds of copies of Knowlton’s book.” When they were not arrested, “Besant and Bradlaugh renotified the authorities that they were selling a supposedly obscene book and were informed in turn that papers were being prepared for their arrest and prosecution. On 7 April 1877, Besant and Bradlaugh were arrested and taken into custody.” 7

(L-R) Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh

The Queen vs Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant was highly publicised and became a sensation. Each juror was issued with copies of the booklet “in order to avoid the embarrassment of reading certain passages out loud.” 6 The prosecution was led by Sir Hardinge Gifford, the Solicitor-General, who described the booklet as “a dirty, filthy book”, claiming that “no human being would allow that book to lie on his table” and that “no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have it.”

During the trial, Bradlaugh and Besant took the unusual step of conducting their own defence. This was particularly remarkable for Annie Besant, whose “appearance in the courtroom posed a challenge to a gendered legal system.” 7 For Chandrasekhar, Besant’s involvement in the trial provided “the spectacle of an educated and prominent woman, running the risk of ostracism and imprisonment, stoutly defending the right to discuss birth control.” 9 As Besant herself put it, “I risk my name, I risk my liberty; and it is not without deep and earnest thought that I have entered into this struggle.” 4 For Besant, her motivation came not from her own ambition, but from her responsibility to “speak as counsel for hundreds of the poor, and it is they for whom I defend this case.” 4

Whilst Bradlaugh and Besant were originally found guilty, the judgement was subsequently set aside on a technicality, and both defendants walked free.

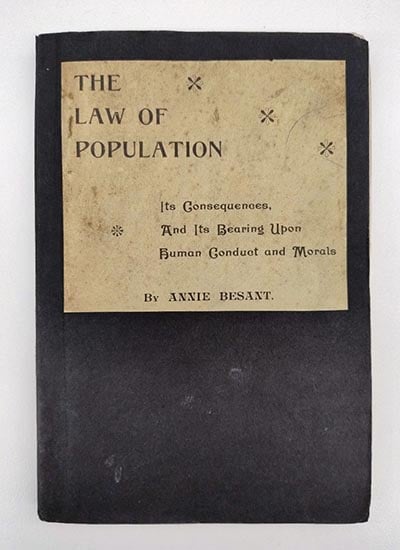

Following the trial, Besant quickly published a new pamphlet of her own to replace Knowlton’s Fruits of Philosophy, which she considered to be outdated. Entitled The Law of Population: Its Consequences, And Its Bearing Upon Human Conduct and Morals, Besant’s text was a huge commercial success. By the time it was withdrawn from publication in 1891, “it had sold 175,000 copies in England, it had been reprinted in the United States and Australia, and it had been translated into German, Dutch, Italian, and French—making it among the most widely circulated tracts on contraception in its time.”7

Annie Besant’s The Law of Population: Its Consequences, And Its Bearing Upon Human Conduct and Morals. n.d. RANZCOG Frank Forster Library.

Legacy in the RANZCOG Collection

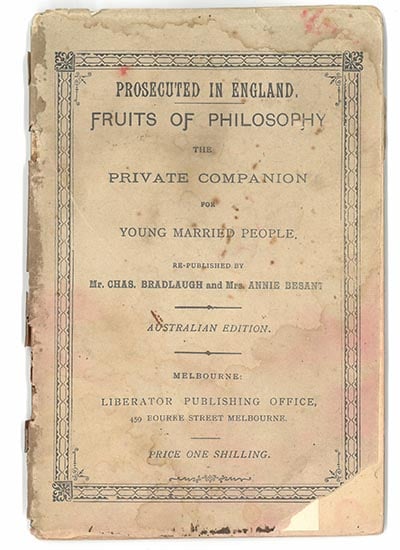

The College’s Frank Forster Library holds multiple copies of Fruits of Philosophy as published by Bradlaugh and Besant in its collection, indicating its importance as a seminal text in the field.

The earliest copy held in the library dates from 1880 and makes an interesting contrast with a later 1894 Australian edition of the booklet, also held in the library. Each is approximately 18 to 19cm high, so physically much larger than Knowlton’s initial publications.

Fruits of Philosophy, 1880 editions. RANZCOG Frank Forster Library.

Fruits of Philosophy,1894 editions. RANZCOG Frank Forster Library.

The 1880 copy of the booklet is fairly understated. Charles Knowlton is referenced on the cover of the booklet, while Besant and Bradlaugh’s role in the publication is only noted in small print on the inside. The 1894 edition makes for a very different story. In this edition, Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant are mentioned in bold print on the cover, and the title itself has been given the second line of billing to the sensationalist proclamation, ‘Prosecuted in England’. Interestingly, Knowlton seems to have been completely disassociated from this edition of the booklet, with his authorship only acknowledged in the text of the preface. If you wanted to know what ‘clickbait’ looked like in 1894, this is it!

Annie Besant was a remarkable woman, whose involvement in the birth control debate in the 1870s did a considerable amount to bring the issue into the public domain. Her collaboration with Charles Bradlaugh to publish the Fruits of Philosophy in 1877, and her outspoken defence of birth control, was crucial to changing the narrative around contraception in society.

These texts, along with a number of other texts written and published by Annie Besant, are part of the Frank Forster Library collection held at Djeembana College Place in Naarm Melbourne. Members and trainees are invited to visit the College to view these fascinating insights into obstetrics history.

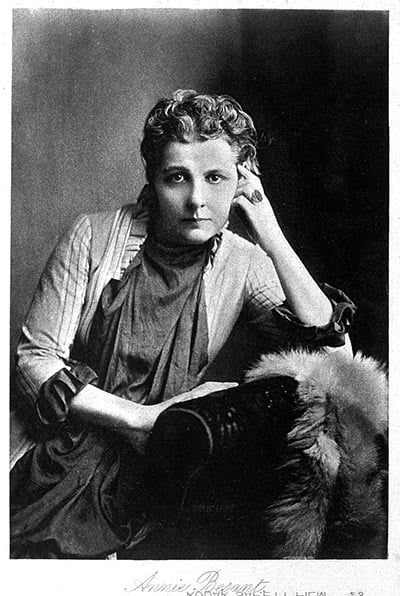

Portrait of Annie Besant (1849-1933). Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

References

- Nunez-Eddy M, Meek C. The Fruits of Philosophy (1832), by Charles Knowlton. Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Arizona State University. 2017. Accessed January 15, 2025. embryo.asu.edu/pages/fruits-philosophy-1832-charles-knowlton

- Green J. A Few of Our Favourite Things, Part One: Charles Knowlton’s Fruits of Philosophy. The Library Company of Philadelphia. 2013. Accessed January 15, 2025. librarycompany.org/2013/09/18/a-few-of-our-favorite-things-part-one-charles-knowltons-fruits-of-philosophy/

- Cooperwood M, Hawley C. Knowlton’s Fruits of Philosophy. Resistance in Early American History. University of Michigan. n.d. Accessed January 15, 2025. courses.lsa.umich.edu/resistance-in-early-american-history/knowltons-fruits-of-philosophy

- Besant A. Annie Besant: An Autobiography. Third impression. The Theosophical Publishing House; n.d.

- Janssen F. Talking about Birth Control in 1877: Gender, Class and Ideology in the Knowlton Trial. Open Cultural Studies. 2017;1(1):281-290. doi: doi.org/10.1515/culture-2017-0025

- Manvell R. The Trial of Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh. Elek Books; 1976

- Sreenivas M. Birth Control in the Shadow of Empire: The Trials of Annie Besant, 1877–1878. Feminist Studies. 2015;41(3):509-537. doi: doi.org/10.1353/fem.2015.0042

- The Queen v. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant (Specially Reported). Second Edition. Freethought Publishing Company; n.d.

- Chandrasekhar S. “A Dirty Filthy Book”: The Writings of Charles Knowlton and Annie Besant on Reproductive Physiology and Birth Control and an Account of the Bradlaugh-Besant Trial. University of California Press; 1981.

Leave a Reply