Dr Val Colley (nee Chaffer who was known professionally by her maiden name) graduated from The University of Sydney in 1947 and went on to become a key obstetrician gynaecologist in Adelaide. She recently celebrated her 100th birthday. This article, which is based on a series of interviews, offers insight into the evolution of obstetrics and gynaecology over the past century

Tell us about your early life.

Our family lived at Chum Creek, near Healesville in Victoria. My father worked in the general store. He was self-taught, educating himself using the town’s first crystal radio.

My sister was the smallest premature baby at the time. She was kept alive, wrapped in cotton wool. My grandmother, Eleanor Lucas, who founded a clothing factory in Ballarat, kept her alive with droplets of whisky. Three years later, when my mother had me, she endured a grinding three-day posterior labour. As a result, she had deep vein thrombosis and was bedridden for three months with sandbags so she couldn’t move her leg. I think she was depressed for a long time after this.

I walked three miles to the one-room school, from the age of three and a half because I wouldn’t stay home. The teacher gave me a nursery rhyme book, but I got bored so I would learn whatever went on with the classes. I was treated like a boy by my father, given a tomahawk and allowed to roam around on my own in the bush.

When I got into high school—the first child in the family to do so—the history teacher told me, “Val, your writing is like the peregrinations of an inebriated fly!”

What was university like?

I went to the University of Sydney in 1942. My mother was worried because she had heard about the Japanese submarines in Sydney Harbour. We did the six-year course in five years by not having holidays, because they wanted to get doctors through faster. I would never have gone to university without the Commonwealth Scholarship.

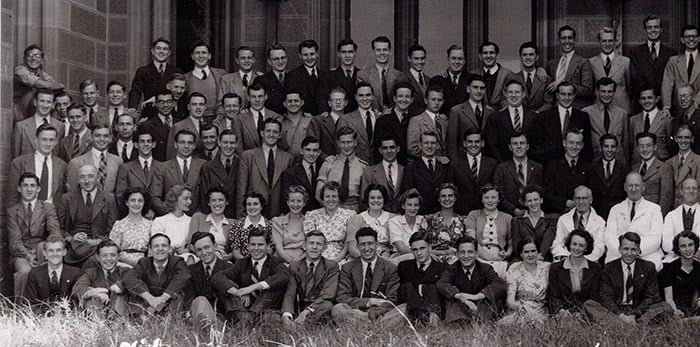

There were 250 students but only 50 women. No, I did not feel sexism in the course, but the minute we got out into the real world, that is when it hit.

I had made up my mind that I wasn’t going to marry a doctor, because if you did, you stayed home and did the domestic work while your husband was out there doing interesting things.

Graduating Class of the University of Sydney, 1947. Dr Val Chaffer is pictured in the second row, sixth from the left

What were your early years of training like?

I started at Prince Alfred where they kept giving me all the surgical rotations—orthopaedics, ear nose and throat, men’s urology, which I found dreadful! Gynaecology I did do, but they still did not give me obstetrics. In my second year, they gave me neurosurgery which was very exciting and wonderful.

I was headhunted to a general practice in Lithgow in New South Wales. As a GP, I had a maternal death that I never got over. The woman delivered precipitously and had a massive haemorrhage. I found out later that she had been to an illegal provider of abortions numerous times, likely sustaining a ruptured uterus from the damage.

One weekend, a doctor in a smaller town rang me to say he had a woman in labour with her 13th baby who could not birth. He asked me if I would take her. I had enough training to know that she had a brow presentation of a big baby, the baby was not alive, and she had stopped labouring. I knew you did not do a caesarean section on a dead baby, so I rang the Crown Street Women’s Hospital in Sydney, and Dr Reg Hamlin answered the phone. He asked me to send the woman to him. The following day, he called and said, “She’s safely delivered. And do you want a job?”.

So, you resigned and went?

Yes. Crown Street was the most drastic and odd hospital. It had greatest number of deliveries in the Southern Hemisphere at that time. Dr Reg Hamlin was the kindest, loveliest person, but he was an extremely hard taskmaster as far as work was concerned.

At the time, eclampsia was the biggest threat to childbirth. Dr Reg Hamlin began to associate it with rapid weight gain, and younger mothers. He would check every night after outpatients, and if he saw someone in that category, he would admit them to a special pre-birth ward and put them on bedrest. One of my most awful jobs was to sedate them with paraldehyde to keep their blood pressure down to reasonable limits. It was a painful, 10ml, awful injection into the backside but the paraldehyde sedated them safely, and Dr Hamlin never had a case of eclampsia in a booked patient.

Dr Catherine Nicholson, who was a resident a year ahead of me, eventually became connected with Dr Hamlin, 15 years her senior. There is a nice little love story that went on over years. They tried to keep it secret, but everybody knew what was going on. And they went on to do fabulous work in fistula care.

Dr Hamlin was the absolute master of manual removal for a retained placenta. The first time I ever did it, while I was still a student, I thought I was removing the liver. He was also able to rotate a posterior delivery by simply putting a hand on the woman’s abdomen, finding a shoulder and turning it manually! I could never do it, even though I tried!

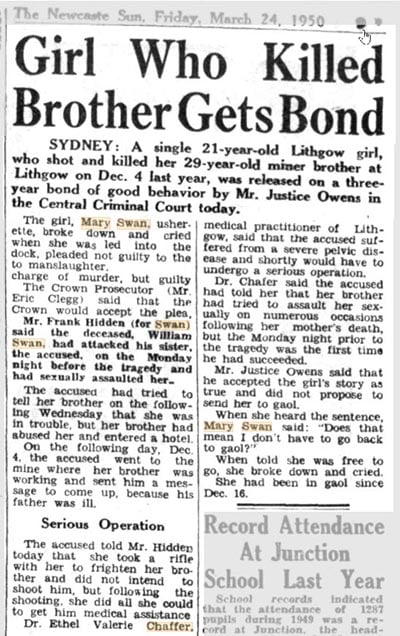

Sydney Morning Herald clippings of Dr Val Chaffer’s testimony in manslaughter case

Sydney Morning Herald clippings of Dr Val Chaffer’s testimony in manslaughter case

How did you meet your husband?

I was bridesmaid for my friend Betty and her cousin Ken was at their wedding. I did not notice him much. Their grandfather said “Ken, get the girls a drink.” So, Ken opens a cupboard and brings out the silver goblets, puts wine in them, and gives them to Betty and me, and they had moths floating in it! It was not the best first impression.

I have never been able to explain it, but by the time I left the wedding, we assumed we were going to get married. I knew him for a year before I got married. I was a career person and Ken said he was perfectly happy to support me. I said I married Ken because I was convinced of his essential goodness, full stop.

I got pregnant on my honeymoon. I had an image of what a baby was going to be, but she was not like that at all. I only breastfed one of my five babies properly, and it is hard to explain, you have got to start off right from the beginning or it does not gel. Ken got a fruit and vegetable shop in Adelaide, which was something he had never done. We moved to Adelaide when my fourth child was only six weeks old. Ken went over in the car with our eldest, and I went on the train with the baby in the carrycot and the two others.

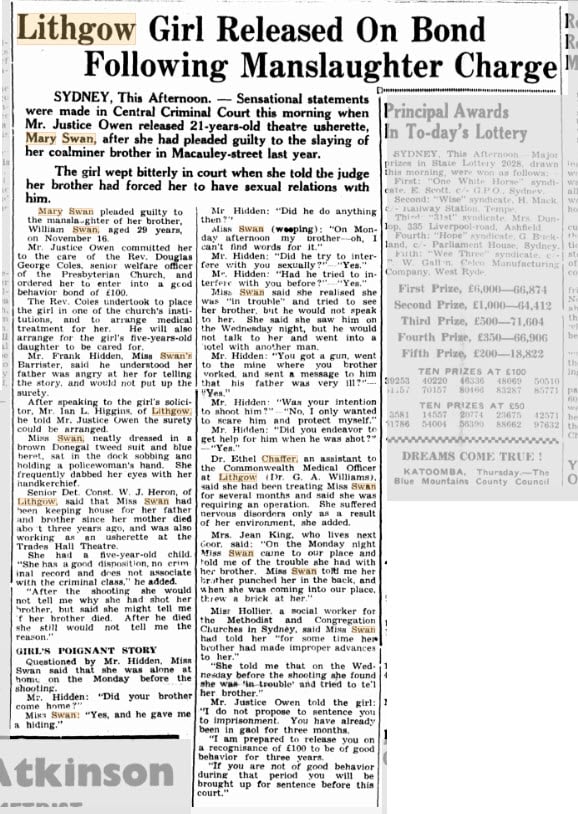

Sydney Unitversity co-conspirators (circa 1990) Dr Val Chaffer and Catherine Hamlin

What was your life in Adelaide like?

I set up practice in a two-storey house just across the road from Lyell McEwin Hospital.

Ken was really busy, up early to go into the markets. I found a nice lady to care for my home and later other housekeepers. All the children remember having to wait for me, either because I was doing home visits and they were in the car with me, or waiting to be picked up, and they were the last children to be picked up.

I planned the surgery with some special things in mind, like how people do not like to be grouped. I learned that privacy was important and made sure only essential questions were asked at the reception desk.

When my daughter reached year six, the school asked the local female doctor to come and do the puberty education. And of course, I practiced in my maiden name. Her friends realised it was me, and she was mortified to have her mother up on stage talking about embarrassing things.

Later, my next daughter came home from school and said, “The nuns said you can get pregnant from a doorknob.” I stopped, then said, “Depends what you do with the doorknob!”

Where did you go with obstetrics?

My whole reason for being an obstetrician was to have women be in charge as far as they possibly could, and to have no fear about their childbirth. The English obstetrician, Dr Grantly Dick-Read, had introduced relaxation for childbirth. I remember reading his book while I was at Crown Street Women’s Hospital. Textbooks did not tell women how it felt to have a baby. I was always very annoyed with the textbooks!

My whole reason for being an obstetrician was to have women be in charge as far as they possibly could, and to have no fear about their childbirth.

Dr Grantly Dick-Read recognised that fear was the greatest inhibitor of labour. I did not like medicalisation, especially of childbirth. I always wanted to let the body do the job that it was intended to do. If you left it alone it did very well. My philosophy was “keeping normal things normal”.

Then came another system called psychoprophylaxis – a special breathing in stages of labour. That came out of Russia, because most of the doctors in Russia were women interestingly enough. Dr Fernand Lamaze was the person who wrote this stuff up. I got physiotherapists who understood the Lamaze to help teach the breathing to a lot of intelligent women, and to the husbands if they wished, to be prepared and come into the labour ward as well. Unbeknownst to me, it was illegal in the hospital for husbands to be present at the birth.

I remember the first woman who used this technique, she had the most beautiful delivery I have ever seen. The next day, I was summoned to the office of the secretary at the hospital, a bloke saying, “You can’t do that (have husbands present at birth). Any husband who wanted to be with his wife in the labour ward was either abnormal, or indecent.” Now I have gotten angry a few times in my life, and when I get angry, something happens. I got the head sister (nurse/midwife) of the labour ward onside. Before too long, we had husbands in the labour ward.

In 1963, I started the Childbirth Education Association. This group formed a hub for prenatal education. I discovered that around Australia that there were various organisations to help people cope with labour. We ran classes, but instead of having professionals doing it all, the mothers did the training. They had professional input from a couple of the leading gynaecologists in the town, plus me. I have always approved of people doing it for themselves with some professional help, but not the professionals being ‘boss’ of everything, because that takes away independence.

It was not about feminist thinking—It was not. It was just to do with the fact that knowledge drives out fear. If you take the fear out of it, you take most of the pain out of it, but of course there were lots of other ways. Later, I worked with hypnosis during the childbirth experience. In middle age, I went out and did a course in transcendental meditation, and laughed and said, “I know how to do this anyway!”

Portrait of Dr Val Chaffer, submitted to the Archibald Prize 1947 by Molly Johnson

And you had some other battles?

Of course, all the time. Isn’t it funny that all my life I never believed that I am an angry person? At one point, I was told we would not have the sisters (nurses) do smears. I insisted that they were better than many doctors, because they were much fussier and more responsible. I held out, and the board said I couldn’t do that. I was told, “You’ll have to ask the head of unit.” That was my friend, and I told him, “You’re not going to stop me!” That bloke knew that if I believed in it, I would do it no matter what. And so I did.

One day, while scrubbing in theatre, I said to my colleague, “I’m going to work at Elizabeth Women’s Health Centre.” The other woman doctor said, “What? That bunch of lesbians?!” The gynaecologist who knew me really, well laughed, and said, “Ha! They don’t know they’ve got a tiger by the tail!”. I reckon that was the best compliment I have ever been given, because he knew that when I got into doing something that I fiercely believed in, I just did it. The Elizabeth Women’s Centre (Adelaide) would give me an hour to work with someone, which meant that I could do everything. I would do their smears and their breast checks, and then I would have time to go into other things, like worries, strategies for headaches, relaxation techniques, eventually I ran a meditation group there one day a week.

When something new comes into the medical orbit, it takes around 15 years to accept, and I could get quite rude about that and say it must be accepted, because everybody is doing it anyway by that time. A lot of these ideas about self-help and alternative medicine—if you are not trained in it, you can be suspicious about a lot of those preparations. But then there have been civilisations and generations of people who have done their medicine differently. Whether it is Native American Indians, or Ayurvedic medicine in India, or those in China with acupuncture and Chinese medicines, they are valid medicines, but Western medicine has difficulty swallowing that. Most importantly, if you have a doctor who really listens to you, and knows where you’re at, you will do better with that person and you will get better quicker. There’s a lot of literature about this.

Do you think of yourself as being a political person?

No. Political only in the sense of believing in empowering people to take charge of themselves. I was apolitical, except for when women’s issues were concerned.

Tell us about non-medical interesting things about your life.

My portrait was entered into the Archibald Prize 1947. Molly Johnson, who attended the Heidelberg School in Melbourne, painted it. And I had a chess move named after me. I had this old gentleman who invented a special chess move. He dedicated this chess move to Dr Chaffer, which was very embarrassing!

What have been your greatest joys?

Oh, I would have to say the children. Practice was marvellous. Okay, work and children.

Dr Val Chaffer (Colley) celebrated her 100th birthday in September, with her five children and ten grandchildren. Her deafness now makes things tricky, but she continues to enjoy a glass of bubbles, her view of an expansive garden and the ability to laugh. Her writing remains atrocious.

Dr Melanie Thompson is a paediatrician in the Kimberley and did not know much about her legendary Great Aunt until medical school.

Leave a Reply