The choice of fetal heart rate monitoring method is a key decision for pregnant women. The selection of either IA (IA) or cardiotocography (CTG) shapes women’s experiences of their birth, and potentially impacts on mode of birth and perinatal wellbeing. RANZCOG recommends women are offered information on intrapartum fetal monitoring and support for decision making.1

Most women want to participate in decisions about their maternity care2, including decisions about fetal monitoring.3 Researchers have repeatedly confirmed a lack of informed consent for intrapartum CTG use in many high-income countries where CTG use is commonplace.3-11 Women completing the Having a Baby in Queensland 2010 survey were asked whether they were given information and choice for a range of common intrapartum procedures9. Only 9% reported having both been given information and a choice about fetal monitoring. This continues to be an issue. Recent qualitative research on Australian women’s experiences with intrapartum fetal monitoring noted a major concern was a lack of information and choice about fetal monitoring options.8

Knowledge is key

Maternity professionals report the decision of whether to use IA or CTG monitoring is driven by hospital policy.11,12 Mandatory hospital policies with wording indicating that some women “require” or “must have” CTG monitoring place professionals in a difficult position. Staff offering women the opportunity to make decisions about intrapartum fetal monitoring would be in breach of policy.

Other factors identified as drivers for the use of CTG monitoring include under-staffing, faith in technology, fear of liability, and social pressures.12 Maternity professionals must possess accurate knowledge about fetal monitoring if they are to provide accurate information to support decision-making.

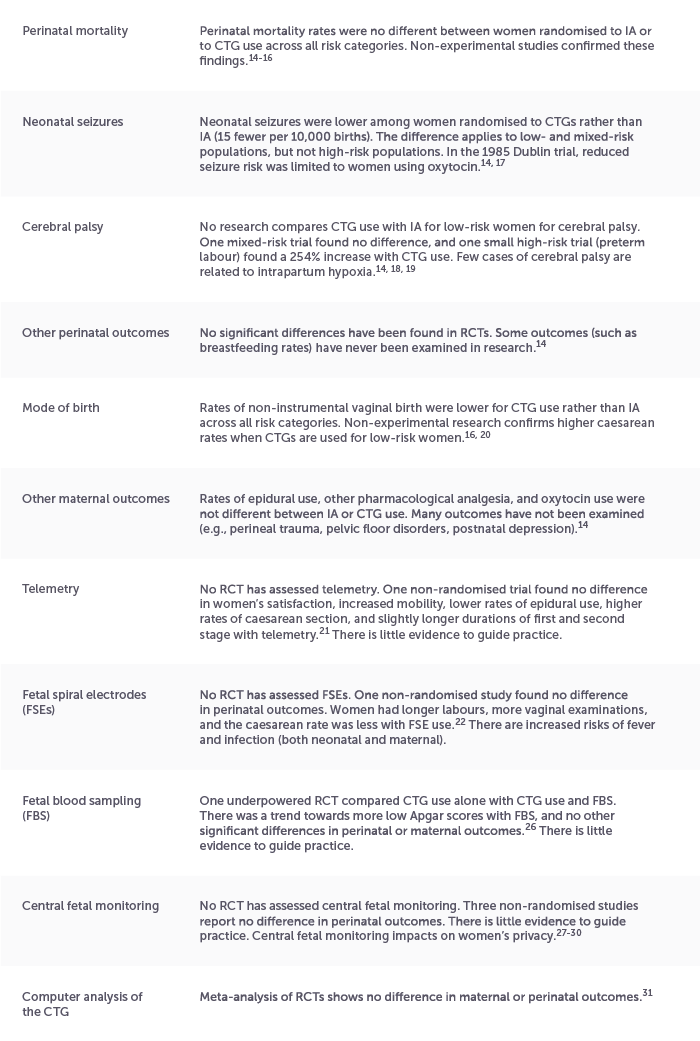

The current edition of the RANZCOG guideline1 provides only two paragraphs about the evidence base for CTG use in the introductory section of the guideline, pointing out the absence of quality evidence. RANZCOG’s Monitoring the Baby’s Heart Rate in Labour pamphlet13 describes both IA and CTG monitoring but does not include sufficient information to enable women to make an informed decision. It incorrectly asserts that fetal blood sampling may prevent the rise in caesarean sections seen with CTG use. Table 1 outlines information that should be included in conversations with all women (regardless of risk) to support their decision-making.

Table 1. Information that should be discussed to enable an evidence-informed decision. Design: Amber Spiteri

The recommendation to inform and involve women in decisions about fetal monitoring set out in the RANZCOG guideline is not being met consistently. Policy reform is needed to ensure women’s role as decision-maker is clear. RANZCOG could better support maternity professionals to have accurate, evidence-based discussions by updating their patient information pamphlet.

Dr Kirsten Small is a researcher, writer, educator, and retired obstetrician/gynaecologist. Her doctoral research examined central fetal monitoring. Her blog, Birth Small Talk, and online courses provide evidence-based education about fetal heart rate monitoring and can be found at: birthsmalltalk.com.

References

- Intrapartum fetal surveillance clinical guideline. 4th Edn. 2019.

- Watkins V, et al. Labouring Together: Women’s experiences of “Getting the care that I want and need” in maternity care. Midwifery. 2022;113:103420.

- Hindley C, et al. Pregnant womens’ views about choice of intrapartum monitoring of the fetal heart rate: A questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(2):224-31.

- Hindley C, Thomson AM. The rhetoric of informed choice: perspectives from midwives on intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Health Expect. 2005;8(4):306-14.

- Blix E, Öhlund LS. Norwegian midwives’ perception of the labour admission test. Midwifery. 2007;23(1):48-58.

- Heelan-Fancher LM. Patient advocacy in an obstetric setting. Nurs Sci Quart. 2016;29(4):316-27.

- Logan RG, et al. Coercion and non‐consent during birth and newborn care in the United States. Birth. 2022.

- Fox D, et al. Tending to the machine: The impact of intrapartum fetal surveillance on women in Australia. PLoS One. 2024;19(5):e0303072.

- Thompson R, Miller Y. Birth control: To what extent do women report being informed and involved in decisions about pregnancy and birth procedures? BMC Preg Childbirth. 2014;14:62.

- Miller YD, et al. A direct comparison of patient-reported outcomes and experiences in alternative models of maternity care in Queensland, Australia. PLoS One. 2022;17(7):e0271105.

- Small KA, et al. The social organisation of decision-making about intrapartum fetal monitoring: An Institutional Ethnography. Women & Birth. 2023;36(3):281-9.

- Chuey M, et al. Maternity providers’ perspectives on barriers to utilization of intermittent fetal monitoring: A qualitative study. J Perinatal Neonatal Nurs. 2020;34(1):46-55.

- Monitoring the Baby’s Heart Rate in Labour. 2021.

- Alfirevic Z, et al. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2017;2(CD006066):1-137.

- Small KA, et al. Intrapartum cardiotocograph monitoring and perinatal outcomes for women at risk: Literature review. Women & Birth. 2020;33(5):411-8.

- Heelan-Fancher LM, et al. Impact of continuous electronic fetal monitoring on birth outcomes in low-risk pregnancies. Birth. 2019;46(2):311-7.

- MacDonald D, et al. The Dublin randomized controlled trial of intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. AJOG. 1985;152(5):524-39.

- Shy KK, et al. Effects of electronic fetal-heart-rate monitoring, as compared with periodic auscultation, on the neurologic development of premature infants. NEJM. 1990;322(9):588-93.

- Wang Y, et al. Exome sequencing reveals genetic heterogeneity and clinically actionable findings in children with cerebral palsy. Nat Med. 2024;30(5):1395-405.

- Medley N, et al. Interventions during pregnancy to prevent preterm birth: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2018;11:CD012505.

- Watson K, et al. Experiences and outcomes on the use of telemetry to monitor the fetal heart during labour: findings from a mixed methods study. Women & Birth. 2022;35(3):e243-e52.

- Harper LM, et al. The risks and benefits of internal monitors in laboring patients. AJOG. 2013;209(1):38.e1-6.

- Siddiqi SF, Taylor PM. Necrotizing fasciitis of the scalp. Am J Dis Child. 1982;136:226-8.

- de Leeuw JP, et al. Mortality and early neonatal morbidity in vaginal and abdominal deliveries in breech presentation. J Obs Gyn. 2002;22(2):127-39.

- Davey C, Moore A. Necrotizing fasciitis of the scalp in a newborn. Obs & Gyn. 2006;107(2):461-3.

- East CE, et al. The addition of fetal scalp blood lactate measurement as an adjunct to cardiotocography to reduce caesarean sections during labour: The Flamingo randomised controlled trial. ANZJOG. 2021;61(5):684-92.

- Weiss PM, et al. Does centralized monitoring affect perinatal outcome? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 1997;6(6):317-9.

- Withiam-Leitch M, et al. Central fetal monitoring: effect on perinatal outcomes and cesarean section rate. Birth. 2006;33(4):284-8.

- Brown J, et al. Birth outcomes, intervention frequency, and the disappearing midwife-potential hazards of central fetal monitoring: a single center review. Birth. 2016;43(2):100-7.

- Small KA, et al. “I’m not doing what I should be doing as a midwife”: An ethnographic exploration of central fetal monitoring and perceptions of clinical safety. Women & Birth. 2022;35(2):193-200.

- Campanile M, et al. Intrapartum cardiotocography with and without computer analysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(13):2284-90.

Leave a Reply