It’s 2016, and the duty registrar, Kate*, walks towards room 6. It’s her third night shift, and she’s been called due to a prolonged second stage. On entering, there’s a midwife and her student. The room is dimly lit, but she sees the familiar look on Olivia’s face: the mix of fear and relief. The midwives like Kate. She’s a safe pair of hands, a quick mind, and kind with her words. She gets to work.

Fast-forward to 11th March 2023, and Olivia stands in the Preston Stanley Room at Parliament House in Sydney — the first of the New South Wales Select Committee on Birth Trauma community hearings.’

The midwife and obstetrician went outside the room for their discussions. The doctor told me: “We’ll use a vacuum to get the baby out,” without discussing the risks or asking for my consent. They tried the vacuum…then proceeded with an episiotomy and forceps without my knowledge. I had never heard of a third-degree tear until two days later.

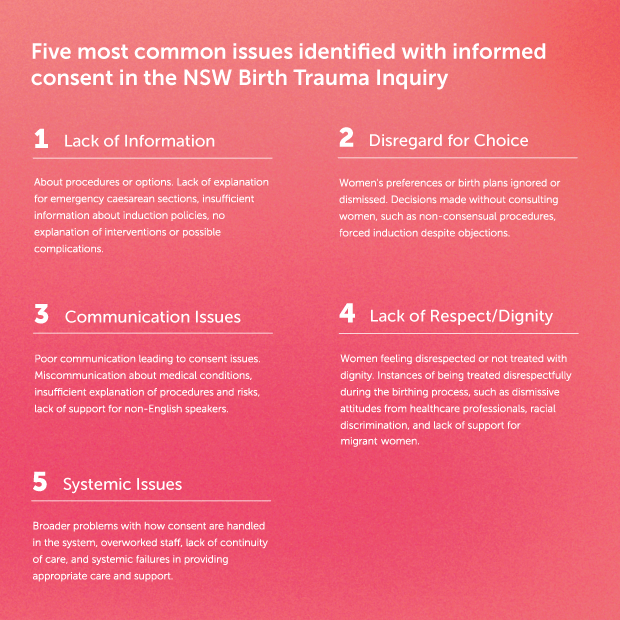

Over 4,000 submissions were received, and the lack, or absence of, informed consent was prominently featured in the birth stories they heard. Figure 1 outlines the five most frequently identified themes.1

Figure 1. Five Most Common Issues Identified with Informed Consent. Design: Amber Spiteri

The evolution of informed consent

Medical paternalism was universal in the early 20th century. Doctors were seen as the ultimate authorities. There was no need to involve patients in treatment matters, and this was no different in the context of labour. The woman’s role was to comply with all medical recommendations.

The mid-to late 20th century saw a gradual shift towards patient-centred care. Civil rights and feminist movements contributed to these developments. Several key legal cases were central to establishing informed consent as an expected standard of care. In gynaecology, pelvic mesh consent issues came to light in the mid-2010s with widespread public awareness, lawsuits, and, in Australia, the 2017 Senate Inquiry.

A review of the research literature on informed consent in labour reveals that before 2010, anaesthetic concerns about the challenges of informed consent for epidurals were the most examined topic.2 By 2017, the themes moved through questions about the ability of intrapartum women to provide consent for research to the implications of the UK Montgomery ruling.3

Over the past ten years, the breadth of research concerning consent in labour has reflected the evolving public expectations and challenges of the medical profession. These centred on ethical considerations, episiotomy, induction of labour, human rights and the intrapartum implications of published guidance, such as the 2020 NSW Consent Manual.4

Today, informed consent in labour requires comprehensive antenatal education, clear communication and meticulous documentation. Challenges remain, especially when time-critical interventions are needed. The 2024 NSW Birth Trauma Inquiry findings indicate work still needs to be done.

Time pressure and communication challenges are considerations for obstetricians who must respond to rapidly evolving situations during intrapartum care. Not only is urgency required for decision-making and actions, but there’s also a need to ensure the patient understands the implications of proposed interventions and can provide valid consent.

Many factors can impede communication and understanding, such as a lack of childbirth education or language and cultural barriers, which impact how information is received or interpreted. Additionally, stress, pain, and fear during labour can hinder information processing.

Practice recommendations

Childbirth education is an enabler for informed consent. Education about potential interventions must include why they might be recommended, their benefits and risks, and possible complications. Education establishes a common language, empowers women to be involved in decisions, and, where relevant, have their preferences clarified and documented in the medical record.

A more positive birth outcome will result when women are informed, empowered and able to have their preferences and autonomy respected. There is evidence that increased labour agentry mitigates post-traumatic stress disorder.5,6,7 Critical components of agentry include autonomy, empowerment, informed consent and collaboration. Agentry in labour recognises the woman as the central figure in the birth process and promotes her ability to make choices that best suit her needs and desires while being supported by her healthcare team.

A 2018 Queensland guideline8 on antenatal education advocated for better information on interventions, citing a 2011 coroner’s report. The coroner recommended discussing the risks and benefits of interventions in antenatal classes facilitated by midwives and obstetricians. However, the guideline relegates this education to clinic settings due to ‘… negative impact that the provision of negative information or risk-based discussion can have on women’s experiences.’

Antenatal education in Australia is mainly led by midwives, with standards set by CAPEA (Childbirth and Parenting Educators of Australia). However, no obstetricians were consulted to prepare these standards.

Obstetricians have often delegated the responsibility of childbirth education to midwives, but this needs to change. We should be present in classes and involved in creating and distributing educational materials, such as leaflets and online videos and engaging in conversations about intrapartum interventions and follow-up question-answering. Without active involvement to ensure comprehensive and accurate information, when called unexpectedly in the second stage of labour, we perpetuate a system that fails to enable informed consent and contributes to postnatal psychological trauma.

Information shared during consent

Obstetricians must provide up-to-date, relevant, and appropriately detailed information about interventions.

Guidance published by RANZCOG on Instrumental Birth and Informed Consent defines expectations for informed consent, as does the Medical Board Code of Conduct. In 2018, a Medical Board of Australia tribunal9 heard an approach—several minutes being taken to discuss the risks and advantages of instrumental delivery vs. caesarean section. The tribunal found that the obstetrician failed to do this and, therefore, failed to obtain informed consent to instrumental delivery. It described this as conduct falling below the standard reasonably expected of a health practitioner.

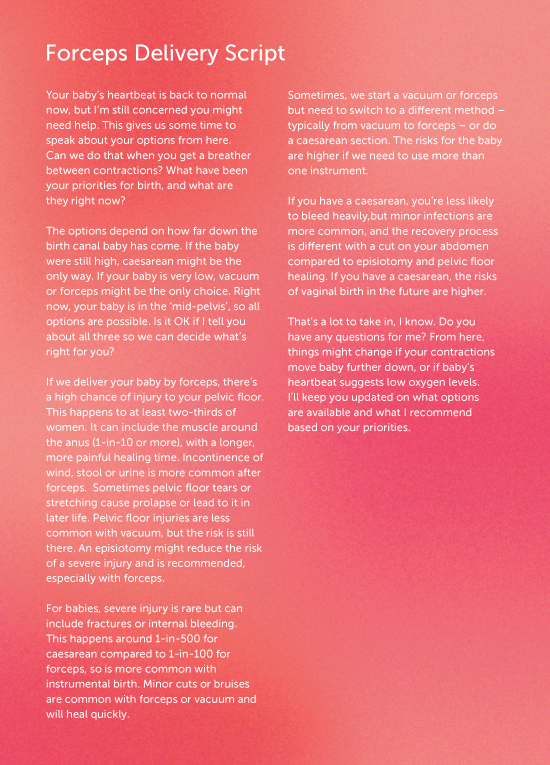

By way of example, Figure 2 outlines an information script shared before a mid-cavity forceps delivery when minimal antenatal education has taken place. It is no longer acceptable to decline to raise the option of a caesarean section or to make statements unsupported by contemporary evidence, such as forceps being safer for the mother and/or baby than a caesarean section.

In 2017, Muraca et al.10 published an analysis of 187 234 births over ten years in Canada, finding that mid-pelvic forceps led to higher rates of pelvic floor and severe perinatal morbidity and mortality as compared with caesarean section. Rates of severe maternal morbidity were similar. Subsequent publications by the same author in 2018 and 2019 have evidenced that the risk profile varies by indication and fetal station.

Conversations during the second stage of labour are incredibly complex, and options often change during the discussion. For this reason, obstetrics skills simulation training should incorporate informed consent and trauma-informed care considerations alongside the technical aspects of instrumental birth.

Where time is even shorter, for example, persistent fetal bradycardia, a briefer approach is needed and is acceptable. Antenatal education will undoubtedly make these discussions more meaningful and less pressured. Documentation templates can ensure the breadth of these discussions is fully reflected in the medical record.

Figure 2. Forceps Delivery: example script for 3-5 minutes of information sharing. Design: Amber Spiteri

Final remarks

Informed consent is crucial for ethical and patient-centred care. The NSW Birth Trauma Inquiry and other studies have shown the harms of inadequate consent. To address this, antenatal education and detailed, empathic communication about birth options are essential. By involving ourselves in these activities, obstetricians can foster a culture of enhanced patient autonomy and improve birth outcomes.

Kate, now a consultant, has evolved her practice. She trains her registrars in the communication skills and trauma-informed care she learned after reflecting on her own practice and changing professional expectations over the last decade. We can rise to the challenge, too.

* All referenced names are fictional, and details have been adjusted for anonymity.

References

- Select Committee on Birth Trauma. Birth Trauma. New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Council.; 2024 May. Report No.: 1

- Black JD, Cyna AM. Issues of consent for regional analgesia in labour: a survey of obstetric anaesthetists. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care. 2006;34(2):254–60.

- Chan SW, Tulloch E, Cooper ES, Smith A, Wojcik W, Norman JE. Montgomery and informed consent: where are we now? BMJ. 2017 May 12;j2224.

- Dietz HP, Caudwell Hall J, Weeg N. Antenatal and intrapartum consent: Implications of the NSW Consent Manual 2020. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2021;61(5):802–5.

- Martinez‐Vázquez S, Rodríguez‐Almagro J, Hernández‐Martínez A, Delgado‐Rodríguez M, Martínez‐Galiano JM. Obstetric factors associated with postpartum post‐traumatic stress disorder after spontaneous vaginal birth. Birth. 2021 Sep;48(3):406–

- Furuta M, Sandall J, Cooper D, Bick D. Predictors of birth-related post-traumatic stress symptoms: secondary analysis of a cohort study. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2016 Dec;19(6):987–99.

- Canfield DR, Allshouse AA, Smith J, Metz TD, Grobman WA, Silver RM. Labour agentry and subsequent adverse mental health outcomes: A follow‐up study of the ARRIVE Trial. BJOG. 2023 Nov 15;1471-0528.17703.

- Recommendations for antenatal education. Content, development and delivery. State of Queensland (Queensland Health), 2018.

- Medical Board of Australia v AB (2018). WASAT 82

- Muraca GM, Sabr Y, Lisonkova S, Skoll A, Brant R, Cundiff GW, et al. Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality after attempted operative vaginal delivery at midpelvic station. CMAJ. 2017 Jun 5;189(22):E764–72.

Leave a Reply