Reproductive genetic screening can promote reproductive autonomy by providing people with information to support informed decision making around future or current pregnancies. There are a variety of reproductive genetic screening options available for people to consider, which can determine their chance of conceiving a pregnancy with a chromosomal or inherited genetic condition. These include prenatal screening for chromosome conditions such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21, or T21) via maternal serum screening or cell free DNA (cfDNA) screening (also known as non-invasive prenatal testing, or NIPT), and preconception or prenatal carrier screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked inherited genetic conditions. With many different pathology providers offering similar but subtly different screening options, it can be challenging for prospective parents to decide what, if any, screening to choose.

What reproductive genetic screening tests are available?

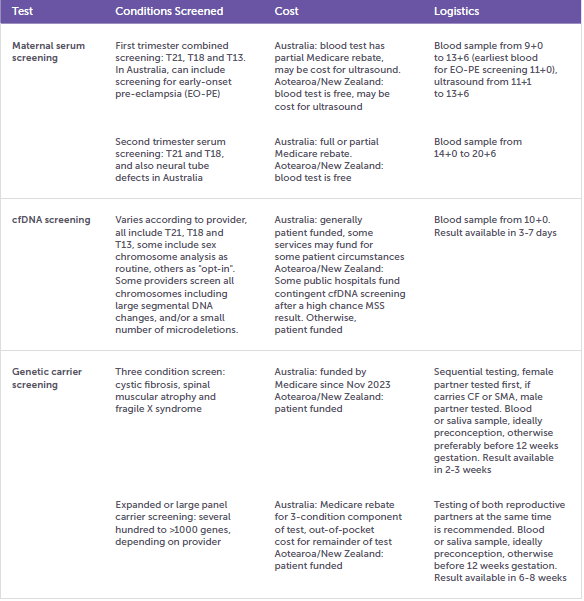

Reproductive genetic screening options include (see Table 1 for more detail):

1. Aneuploidy screening during pregnancy

- Maternal serum screening (MSS)

- First trimester MSS (also called combined first trimester screening) uses a combination of two blood markers, ultrasound measurements and maternal factors to determine the chance of the common trisomies T21, T18 and T13 in a pregnancy.

- Second trimester MSS uses four blood markers and maternal factors to determine the chance of T21, T18 and neural tube defects in a pregnancy.

- cfDNA screening utilises placental cfDNA in the maternal bloodstream to screen for aneuploidy, which can include the common trisomies, sex chromosome aneuploidy (and fetal sex), rare autosomal aneuploidy, large segmental chromosome imbalances and in some cases microdeletions, depending on the technology used.

2. Reproductive genetic carrier screening

- Three condition carrier testing screens the female reproductive partner for carrier status for cystic fibrosis (CF), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and fragile X syndrome (FXS). If the female carries CF and/or SMA, the male reproductive partner is offered testing for the relevant condition/s.

- Large panel carrier testing screens for hundreds of autosomal recessive conditions, and X-linked conditions. Some large panel test providers report individual carrier status, whereas other providers produce a combined couple result, reporting if both reproductive partners carry the same autosomal recessive condition/s, or if the female carries an X-linked condition. When screening for hundreds of conditions, most people screened will be a carrier for one or more condition, thus it is practicable to screen both members of the reproductive couple at the same time.

Table 1. Reproductive genetic screening tests

Who should be offered reproductive genetic screening?

The 2018 RANZCOG Statement Prenatal screening and diagnostic testing for fetal chromosomal and genetic conditions1 recommends that “all pregnant women should be provided with information and have timely access to screening tests for fetal chromosome and genetic conditions”. A common misconception is that genetic carrier screening is only relevant to people with a family history of a genetic condition. However, for women screened for CF, SMA and FXS, 90% of those identified as carriers had no family history of the condition.2

The 2019 RANZCOG Statement on Genetic carrier screening3 recommends that “information on carrier screening for other genetic conditions should be offered to all women planning a pregnancy or in the first trimester of pregnancy. Options for carrier screening include screening with a panel for a limited selection of the most frequent conditions (e.g. cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome) or screening with an expanded panel that contains many disorders (up to hundreds)”.

Informed choice – what do people need to know about genetic screening tests?

In developing a measure of informed choice regarding screening tests offered in pregnancy, Marteau et al4 defined informed choice as “one that is based on relevant knowledge, consistent with the decision-maker’s values and behaviourally implemented”. Van den Berg et al5 later expanded the concept of informed choice to informed decision-making and emphasised that the decision should involve a process of deliberation. Not only is it ethical practice to ensure patients are informed of the purpose, benefits and limitations of screening tests, studies show that informed choice is associated with better patient outcomes and less decisional regret.6 Rather than solely providing information about genetic screening tests, healthcare providers should support patient decision-making that is consistent with the patient’s personal values.7

Ormond et al8 have developed a list of critical components for informed consent for genetic testing which are applicable to reproductive genetic screening. The components provide a guide for health practitioners to facilitate a discussion with their patients around informed choices about genetic screening and testing. The following points should be covered in pre-test counselling:

- Patients should be aware that deciding not to have screening is a valid choice. There are concerns around possible routinisation of testing such as cfDNA screening, in that it may be seen as “just another blood test” if it is offered without appropriate pre-test counselling.9 It is important that patients are aware that results from such screening could have important unexpected implications for their pregnancy, such as the potential for the offer of pregnancy termination if a chromosomal or genetic condition is diagnosed. People should be provided with sufficient time to make an informed decision about genetic screening tests.

- Information regarding the purpose of screening tests, including why the test is done and what conditions, or types of conditions, the test does (and doesn’t) screen for. As testing becomes more complex with many more conditions able to be screened (e.g. whole genome cfDNA screening, large carrier screening panels), it is impossible to discuss every condition being screened. It is reasonable to provide an overview of the types of conditions screened, and to provide people with written or online resources should they wish to explore these in more detail. An explanation of test sensitivity and specificity can be helpful, as well as stating the limitation that no test can detect every possible chromosome condition or genetic carrier, and that a “low chance” result doesn’t guarantee a healthy pregnancy or baby.

- The logistics of the testing process, which includes information such as the sample type required (e.g. blood or saliva for carrier screening), timing of sample collection (e.g. preconception or before 12 weeks gestation for carrier screening, after 10 weeks gestation for cfDNA screening), out-of-pocket costs (some tests have full or partial Medicare rebates), and how long the results will take. For large panel carrier screening, the importance of both partners being screened at the same time should be explained.

- The types of results that patients may receive, how the results will be provided, and by whom. Patients should be aware that aneuploidy screening results provide a risk estimate, false positive and false negative results can occur, and the test doesn’t screen for every possible chromosome condition. Low chance results indicate it is unlikely the pregnancy has a significant chromosome condition, but the chance isn’t zero. High chance results are not diagnostic of a chromosome condition, and further diagnostic testing would be offered if a definitive result is desired. The chance of an increased chance cfDNA screening result being confirmed in the fetus varies according to the chromosome condition detected (positive predictive value). Patients should be made aware that they may receive a “no result”, which may be due to factors such as low fetal fraction or sample quality issues, and retesting at no cost would be an option. For carrier screening, a low chance result indicates that an individual is unlikely to be a carrier for a genetic change in the gene associated with the condition/s screened, or that a reproductive couple are unlikely to have children with any of the genetic conditions screened. However, limitations in test technology and current knowledge around genetic variants mean that not all carriers will be detected. Reproductive couples should be advised if they receive a high chance result for having children with an autosomal recessive or X-linked condition, there are reproductive options available should they wish to avoid passing the condition on.

- Other less common types of results that may potentially be returned. cfDNA screening has the potential to reveal findings that may have implications for maternal health, such as sex chromosome aneuploidy or mosaicism for a chromosome condition, or, in rare cases, an indication of malignancy. In screening tests where individual carrier status is reported, there may be health implications for some carrier results, such as an increased chance of premature ovarian insufficiency in female fragile X premutation carriers.

- How pregnancy management/reproductive planning may be impacted by results of reproductive genetic screening tests. Patients should be aware that embarking on screening could ultimately result in an offer of termination of pregnancy or a change in a couple’s reproductive pathway.

An understandable challenge for healthcare providers is to incorporate this pre-test counselling into their practice in a way that covers the relevant information in a timely manner while minimising information overload. It’s important that healthcare providers have good resources available to provide their patients regarding reproductive genetic screening options. These may include hard-copy or online resources (e.g. fact sheets, brochures, videos, podcasts, decision aids). Some helpful resources around prenatal screening options include the YourChoice decision aid for patients for chromosome screening in pregnancy, developed by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and the Prenatal Screening website developed by Down Syndrome Queensland and the Queensland Health Department. The latter has resources for both patients and health professionals, including a RANZCOG-endorsed Practice Resource.

Post-test genetic counselling

Approximately 2% of reproductive couples will receive a carrier screening result indicating an increased chance for a genetic condition in their children, and a further approximately 2% of pregnant people will receive a result showing a high chance of a chromosome condition in their pregnancy. Research shows that these results are generally unexpected and come as a shock. Disclosure of the result should include some initial information about the condition for which there is an increased chance, the chance of the result being confirmed/passed on to a child, and the next steps that are available. Referral for genetic counselling can be beneficial in providing a supportive environment for people to digest the news, understand the implications of the result and make decisions about further testing/reproductive options. In some scenarios, the condition may be variable, or very rare, so it may not be possible to provide people with definitive information around prognosis, which can be particularly challenging. It is vitally important that healthcare providers are aware of referral pathways for genetic counselling for people who receive increased chance results. A list of clinical genetics services in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand can be found on the HGSA website.

Emotional, psychological and practical support is paramount throughout the experience of receiving unexpected results and subsequent decision-making. Healthcare providers can also provide other resources that may be helpful for support and decision-making for people in this scenario. Through the Unexpected is an organisation providing support for parents who receive a suspected or confirmed prenatal diagnosis of congenital anomaly (throughtheunexpected.org.au). The “One screened every minute” podcast (onescreenedeveryminute.com) features interviews with pregnant people who have received unexpected results from cfDNA screening. Patients seeking more information about a particular condition can also be directed to the relevant patient support organisation for the condition such as Down Syndrome Australia, Fragile X Association of Australia, Cystic Fibrosis Australia, and SMA Australia.

Summary

Research consistently shows that people value the opportunity to understand their chance for genetic and chromosomal conditions and make informed reproductive choices. Practitioners can position themselves to effectively deliver reproductive genetic screening by ensuring they and their patients have access to information resources and support.

Dr Katrina Scarff, BSc(Hons), PhD, MGenCouns, FHGSA, Victorian Clinical Genetics Services, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Parkville, VIC.

A/Prof Alison Archibald, PhD, GDipGenetCouns, GDipArts(Psychology), FHGSA, Victorian Clinical Genetics Services, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Parkville, VIC.

References

- Prenatal screening and diagnostic testing for fetal chromosomal and genetic conditions. RANZCOG statement C-Obs 59. July 2018.

- Archibald AD, Smith MJ, Burgess T, et al. Reproductive genetic carrier screening for cystic fibrosis, fragile X syndrome, and spinal muscular atrophy in Australia: outcomes of 12,000 tests. Genet Med. 2018;20(5):513-23.

- Genetic carrier screening. RANZCOG statement C-Obs 63. March 2019. https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Genetic-carrier-screeningC-Obs-63New-March-2019_1.pdf

- Marteau TM, Dormandy E, Michie S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expect. 2001;4(2):99-108.

- van den Berg M, Timmermans DRM, Ten Kate LP, et al. Informed decision making in the context of prenatal screening. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1):110-7.

- Ames AG, Metcalfe SA, Archibald AD, et al. Measuring informed choice in population-based reproductive genetic screening: a systematic review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(1):8-21.

- Kater-Kuipers A, de Beaufort ID, Galjaard RH, Bunnik EM. Rethinking counselling in prenatal screening: An ethical analysis of informed consent in the context of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT). 2020;34(7):671-8.

- Ormond KE, Borensztein MJ, Hallquist MLG, et al. Defining the critical components of informed consent for genetic testing. J Pers Med. 2021;11(12).

- Metcalfe SA. Genetic counselling, patient education, and informed decision-making in the genomic era. Semin Fetal and Neonatal Med. 2018;23(2):142-9.

Leave a Reply