The science is unequivocal. Increasing levels of anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHGs) carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere are causing the climate crisis1. The climate crisis is a health crisis which will continue to worsen as GHGs accumulate2. Many Australian healthcare organisations have released or endorsed public statements on climate change3,4,5 calling for action. However, healthcare is contributing to this situation. In Australia, healthcare is responsible for 7% of our national emissions6, while 5% of global GHG emissions stem from healthcare7.

Hospitals are the largest sector of Australia’s healthcare emissions, and operating theatres are the most emissions-intensive area within hospitals. Anaesthetists are involved in some of the most environmentally damaging healthcare settings. As such, they are uniquely positioned to drive improvements in these areas, both within our specialty and within the practices of other groups that we interact with day-to-day, particularly surgical teams. As healthcare professionals, we have a duty to reduce our environmental impact for the health of the global population – while maintaining high-quality clinical care. High-value healthcare is low-carbon healthcare8.

Environmentally sustainable healthcare is about providing the same level of exceptional clinical care, for as little environmental impact as possible. A simple framework for considering the environmental impact of healthcare is to look at either associated carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions, or the associated physical waste. There is overlap between these two areas, but it can be useful as a way of envisioning the problem, identifying targets for intervention, and communicating both to staff. There is significant overlap between the environmental issues of anaesthesia and O&G.

Anaesthetic gases

Arguably the most important environmental target in anaesthesia are anaesthetic gases. When these are mentioned, frequently nitrous oxide (N2O) is forgotten in favour of other agents, including sevoflurane and desflurane. N2O is the most impactful of these on the greenhouse effect and therefore our climate crisis. With its global warming potential of 273 times that of carbon dioxide it would be assumed to be less impactful than our other gases, but its long atmospheric lifespan of 110 years, use in greater concentrations, at higher flow rates, and across wider settings by multiple clinical groups result in much higher quantities entering the atmosphere and having a longer-lasting effect. Within anaesthesia itself, its use has been consistently and progressively decreasing over the past several decades. Its use in other areas of the hospital is only recently coming under scrutiny in efforts to reduce its environmental impact. When used in anaesthesia, it occurs within a “closed” breathing circuit; because exhaled gas can be used for the next inhalation to a considerable extent, the volume of N2O used can be significantly reduced when its administration is felt appropriate.

However, in other settings, such as birth suite for labour analgesia, or ED or wards for procedural sedation including in paediatric populations, it is used in “open” breathing circuits, meaning that exhaled gases are not captured, and higher gas flows are required. This results in higher volumes of nitrous oxide used per clinical situation. Wong et al9 calculated that when N2O is used for labour analgesia, the average N2O volume per birth is approximately 500L, compared with approximately 60L per paediatric case in the emergency department, and 50L per theatre case.Importantly, in the last five years researchers have found that N2O infrastructure frequently leaks, resulting in large proportions of purchased N2O being lost to the atmosphere before it reaches patients10,11,12. This issue needs obstetric and midwifery engagement in efforts to address this problem. These systemic leaks can be more than 70% of total N2O purchasing (i.e. only 30% N2O is actually being clinically used). Clinical use of N2O still has a considerable environmental impact, and it’s important to rationalise our clinical use alongside efforts to address N2O leaks.

In the obstetric setting, this includes using it at no higher than 50% concentration for labour analgesia, as evidence suggests that higher concentrations have no greater analgesic effect, but increased rates of side effects. Access to N2O does not appear to change the rate of epidural use13; for those patients who request epidurals, we should be providing these promptly, which requires coordinated efforts from midwifery, obstetric and anaesthetic teams. When N2O is used, use of catalytic cracking devices could be considered to mitigate the impact of the exhaled gas; this new technology captures the exhaled gas and breaks it down into nitrogen and oxygen, which do not produce the greenhouse effect. Our other inhalational anaesthetic agents are still relevant, as all in current use are greenhouse gases. Desflurane has the highest global warming potential, with 2,640 times the effect of carbon dioxide. Its use is reducing, with increasing numbers of Australian hospitals choosing not to supply it. Desflurane was the subject of recent controversy with the well-publicised expression of a dissenting view on its importance, but the majority of those involved in improving the environmental sustainability of anaesthesia, view reduction of its use and its removal from practice as imperative in our climate action.

Sevoflurane is widely used for maintenance of anaesthesia, and its effects have been mitigated with the practice of ultra-low flow anaesthesia – the reduction of fresh gas flows, and therefore the amount of sevoflurane used – becoming increasingly common. The use of the total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA), most commonly with propofol, has dramatically increased in the past decade, and avoids the use of these gases altogether. While not without CO2e, TIVA is environmentally beneficial compared with inhalational anaesthesia, and with additional clinical benefits.

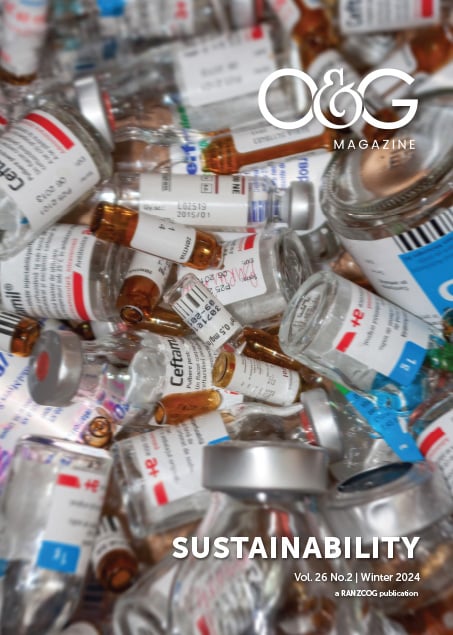

Single-use items

Single-use disposable equipment in healthcare not only produces enormous amounts of waste, but has associated emissions both before use, in its production, packaging, sterilisation, and transport. Also, many items may be disposed of in clinical waste streams, requiring incineration or chemical treatment. While the reprocessing of reusable items does have associated emissions, these can be diminished or eliminated if electricity and transport are powered by renewable sources14. General aims in this area should be to minimise the use of single-use items; replacing these with reusable items and minimising the use of equipment. One ever-present example in both anaesthesia and O&G is the use of “blueys”– single-use disposable absorbent pads. They are energy, chemical, and water intensive to produce, and take over 100 years to break down. They have good indications for use, but have reusable alternatives. In anaesthesia, they can be replaced with towels, pillowcases, or already opened packaging, all of which avoid a new single-use product being consumed15,16.

In birth suite, often reusable absorbent pads (“Kylies”) are appropriate and can reduce the number of blueys used. We engaged with a local linen supplier to develop a reusable alternative to the bluey, ensuring it met the requirements of birth suite in consistency of weight for weighing blood loss.

Surgical procedures

Surgical procedures are both CO2e and waste intensive. While we can address this by sourcing electricity for the hospital from renewable sources, avoiding opening unnecessary equipment, changing single-use items to reusable items, and ensuring that anaesthetic practices to reduce environmental impact are employed; avoidance of unnecessary operations has a far greater impact and has positive effects beyond the environmental. This is almost entirely within the remit of the proceduralist, though anaesthetic practitioners may be involved pre-operatively for complex elective cases, or in emergency situations. This principle can be extended in O&G to ensuring access to contraception, examining the caesarean rate/indications and considering procedures that could occur in non-hospital settings without general anaesthesia.

Reproductive choice

Each and every human has a significant environmental impact. Despite a slowing rate17, global population growth remains an ongoing issue and contributor to environmental degradation. Supporting and defending our patients’ reproductive choices and rights is of paramount importance to protect the ethical principle of autonomy, but also has secondary environmental benefits. Access to contraception, termination of pregnancies, and permanent sterilisation options when requested and appropriate are crucial. This area is primarily the remit of obstetricians and gynaecologists, but can involve anaesthetists too, in ensuring provision of adequate access to both surgical termination lists and surgical sterilisation procedures.

Environmental sustainability is crucial in healthcare. This is supported by international and national bodies but requires individual clinicians to champion this cause and consider it in their daily work, as well as push their organisations to take action. There are changes required at every level, from individual clinicians to our Government. Collaboration between specialties and craft groups is essential to our success; we must scrutinise our own specialty and identify the practices with the greatest environmental impact, and work with those around us to improve our footprint.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023:pp. 1-34, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001

- Romanello M, di Napoli C, Green C, et al. The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms. Lancet. 2023 Dec 16;402(10419):2346-2394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01859-7

- Australian Medical Association. Climate Change and Human Health – 2004. Revised 2008. Revised 2015. Media release, AMA. Aug 28, 2015. Accessed Apr 22, 2024.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Addressing Climate Change. Media release, ACOG. Nov, 2021. Accessed Apr 22, 2024.

- Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. ANZCA Council Statement on Climate Change. Media release, ANZCA. Jan, 2020. Accessed Apr 22, 2024.

- Malik A, Lenzen M, McAlister S, McGain F. The carbon footprint of Australian health care. Lancet Planet Health. 2018 Jan;2(1):e27-e35. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30180-8

- Lenzen M, Malik A, Li M, et al. The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment. Lancet Planet Health. 2020 Jul;4(7):e271-e279. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30121-2

- Barratt AL, Bell KJ, Charlesworth K, McGain F. High value health care is low carbon health care. Med J Aust. 2022 Feb 7;216(2):67-68. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51331

- Wong A, Gynther A, Li C, et al. Quantitative nitrous oxide usage by different specialties and current patterns of use in a single hospital. Br J Anaesth. 2022 Sep;129(3):e59-e60. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.05.022

- Chakera A. Reducing the impact of nitrous oxide emissions within theatres to mitigate dangerous climate change. Masters. University of Edinburgh; 2020.

- The Nitrous Oxide Project. Centre for Sustainable Healthcare. Accessed Apr 22, 2024.

- Seglenieks R, Wong A, Pearson F, McGain F. Discrepancy between procurement and clinical use of nitrous oxide: waste not, want not. Br J Anaesth. 2022 Jan;128(1):e32-e34. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.10.021

- Gynther A, Pearson F, McGain F. Nitrous oxide use on the labour ward: efficacy and environmental impact. Australasian Anaesthesia. 2021 Oct:183-192. Accessed Apr 22, 2024.

- McGain F, McAlister S. Reusable versus single-use ICU equipment: what’s the environmental footprint? Intensive Care Med. 2023 Dec;49(12):1523-1525. doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07256-9

- Balmaks E, Seglenieks R. Reducing operating theatre bluey use. In: Selected prize abstracts from the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists Annual Scientific Meeting and the Obstetric Anaesthesia SIG Satellite Meeting, May 2023, Sydney, Australia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2023 Dec 7;51(3 supp):1-15. doi:10.1177/0310057X231202616

- Operation Clean Up. TRA2SH. Accessed Apr 22, 2024.

- Ritchie H, Mathieu E. How many people die and how many are born each year? Our World in Data. Jan 5, 2023. Accessed Apr 22, 2024.

Photo credit for Dr Emily Balmaks profile picture: Julia Nance

Leave a Reply