In Tasmania in January 2019, an out-of-control fire in the Tahune forest reserve blanketed the nearby town of Geeveston with thick, choking smoke. Sarah lived with her partner and child on the outskirts of town, in a caravan at the back of her parents’ house. I remember her telling me this when she came to our antenatal clinic for a routine 24-week visit. Her first pregnancy had been uncomplicated, and she had no obvious risk factors for obstetric complications, but two weeks after that appointment, Sarah came to hospital in pre-term labour. Her baby girl died soon after birth.

In January 2019, air pollution was something that I’d never really thought about, although I knew it could exacerbate asthma and cause cardio-respiratory problems. But I couldn’t help but wonder if there was anything I could, or should, have done to help Sarah. As the smoke slowly cleared from Tasmanian skies and then returned later the same year in the most extreme and widespread fires South-Eastern Australia had ever seen, I started to do some reading.

One story stood out. The first person ever in the world to have officially died of air pollution was 9-year-old Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, who lived 25 metres from one of London’s busiest roads and died after an acute asthma attack in 2013. It took seven years of campaigning and evidence from high-profile expert witnesses before a coroner ruled that air pollution had contributed to Ella’s death1. The significance of the finding cannot be overstated: humans are moved to action by their emotional response to individual stories while large, abstract numbers — such as the roughly 8 million premature deaths worldwide attributed to air pollution each year2 — are impossible to process and easy to ignore.

We can’t know for certain what role air pollution played in Sarah’s pre-term birth. However, an unholy combination of bushfire smoke, heat and stress was likely at play, each amplifying the pro-inflammatory effects of the others. There is overwhelming evidence that pregnant women exposed to air pollution are at increased risk of pre-term birth and fetal growth restriction3. But our inability (or unwillingness) to directly attribute causation in individual cases is one thing that prevents us from grappling with the issue. Although one in three pre-term births globally is associated with air pollution4, and a study published in 2023 estimated that over 14% of pre-term births in NSW between 2016 and 2019 were related to wildfire smoke exposure5, the Australian Pre-term Birth Prevention Alliance website does not list air pollution among the potential causes of pre-term birth6.

Another problem is that we seem to feel there is nothing we can do to make a difference — we accept air pollution as an unfortunate but inevitable part of urbanisation and industrialisation. But Government policy and regulation have the power to significantly influence air quality. In the USA, the net economic benefits (mostly derived from health co-benefits) of the Clean Air Act are over two trillion dollars annually, 32 times the cost of the regulations7. But because many of the costs are born by industry, clean air legislation is constantly being challenged and flouted.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recognises air pollution as the single biggest environmental threat to human health. In 2021, the WHO revised its air quality standards to reflect emerging evidence about health effects of even relatively low levels of pollution. They now estimate that 99% of the world’s human population is regularly exposed to unhealthy air8. Of the 1% who enjoy clean air, many live in Australia and New Zealand. But we cannot be complacent. Bushfires, which are becoming more frequent and severe with global heating, can expose large numbers of people to extreme levels of air pollution for extended periods. Other people are exposed to air pollution through residential proximity to industry or heavy traffic, occupation, or poor-quality housing. In Australia and New Zealand and all over the world, the people most likely to be exposed to air pollution tend to live in lower socio-economic areas, are more vulnerable to its health effects due to co-morbidities and interacting exposures, have less capacity to modify their exposure and are less able to advocate for themselves. Air pollution is a social justice issue.

Air pollution tends to be a mix of gases and particulate matter (including black carbon, heavy metals, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). Sources of outdoor (ambient) air pollution include fossil fuel extraction and combustion, other industrial and agricultural activities, bushfires and dust storms. Sources of indoor air pollution include heating and cooking with solid fuels, smoking, candles and incense, mould, off-gassing from new furniture or carpets, fragrances, and cleaning products. Whether indoor or outdoor, and regardless of the source, health effects derive from a complex interplay of increased oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and immune dysregulation. Many pollutants also act as endocrine disruptors. In adults, this leads to increased rates of cardio-respiratory disease, diabetes and metabolic dysfunction, kidney disease, autoimmune disease, cancer, and neurological and psychiatric disorders9. Particulate matter is the most significant cause of health effects; larger particles up to 10 microns in diameter (PM10) are responsible for visible haze and immediate symptoms such as eye and skin irritation and cough, while smaller particles less than 2.5 microns in diameter (PM2.5) reach the alveoli and enter the bloodstream. Effects on pregnancy are predominantly placentally mediated, secondary to inflammation, oxidative stress, epigenetic changes or endocrine disruption. Ultrafine particles can also cross the placenta into the fetal circulation, where they act directly on developing organs10,11. Studies performed in regions where there are chronic, high levels of air pollution consistently show increased risks of pre-term birth, low birth weight and small for gestational age, and stillbirth3. The increase in individual risk is relatively small, but it represents a significant public health issue due to the ubiquity of air pollution. Studies also support a likely or possible increase in gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertensive complications of pregnancy12, and infertility and miscarriage13.

Even in the absence of adverse pregnancy outcomes, in-utero exposure to air pollution is associated with disorders of the respiratory system, immune status, brain development, and cardiometabolic health in children11. Studies of exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons demonstrate associations with developmental delay, reduced IQ, symptoms of anxiety, depression and inattention, ADHD, deficient maturation of emotional self–regulation capacity, and poorer social responsiveness in childhood. In a review of the adverse effects of fossil fuel combustion on child health, and the magnifying effects of climate change and socio-economic deprivation, Federica Perera writes: “Unless strong action is taken now, our children and their progeny will inherit an increasingly unsustainable and unfair world in which they, their families and communities will not be able to survive, adapt, grow and transform where needed.”14

Australian women are most likely to be concerned about episodes of bushfire smoke exposure. The largest studies of bushfire smoke to date have been undertaken in the USA. A Colorado study of over 500,000 exposed pregnancies, showed that for every 1mcg/m3 (trimester average) additional PM2.5 exposure, there was a 5.7g decrease in birth weight, an odds ratio of 1.132 for pre-term birth, and increased risks of gestational diabetes and hypertension15. To put this into context, average PM2.5 levels in Newcastle and Sydney increased from 10mcg/m3 to 26 mcg/m3 over the three months from November 2019 to January 2021. A Californian study of over 3 million births found a 3.4% increase in risk of pre-term birth before seven weeks after seven days of smoke exposure. They also showed that the prime driver of pre-term birth rates was days of very high smoke intensity16.

What can we, obstetricians and gynaecologists, do?

Education is vital. First, we need to educate ourselves. A 2018 USA study of patient-provider discussions around strategies to limit air pollution exposure found that 0% of 250 obstetricians surveyed reported ever discussing air pollution with their patients. I would like to think we can do better in Australia and New Zealand, but we have some work ahead of us17.

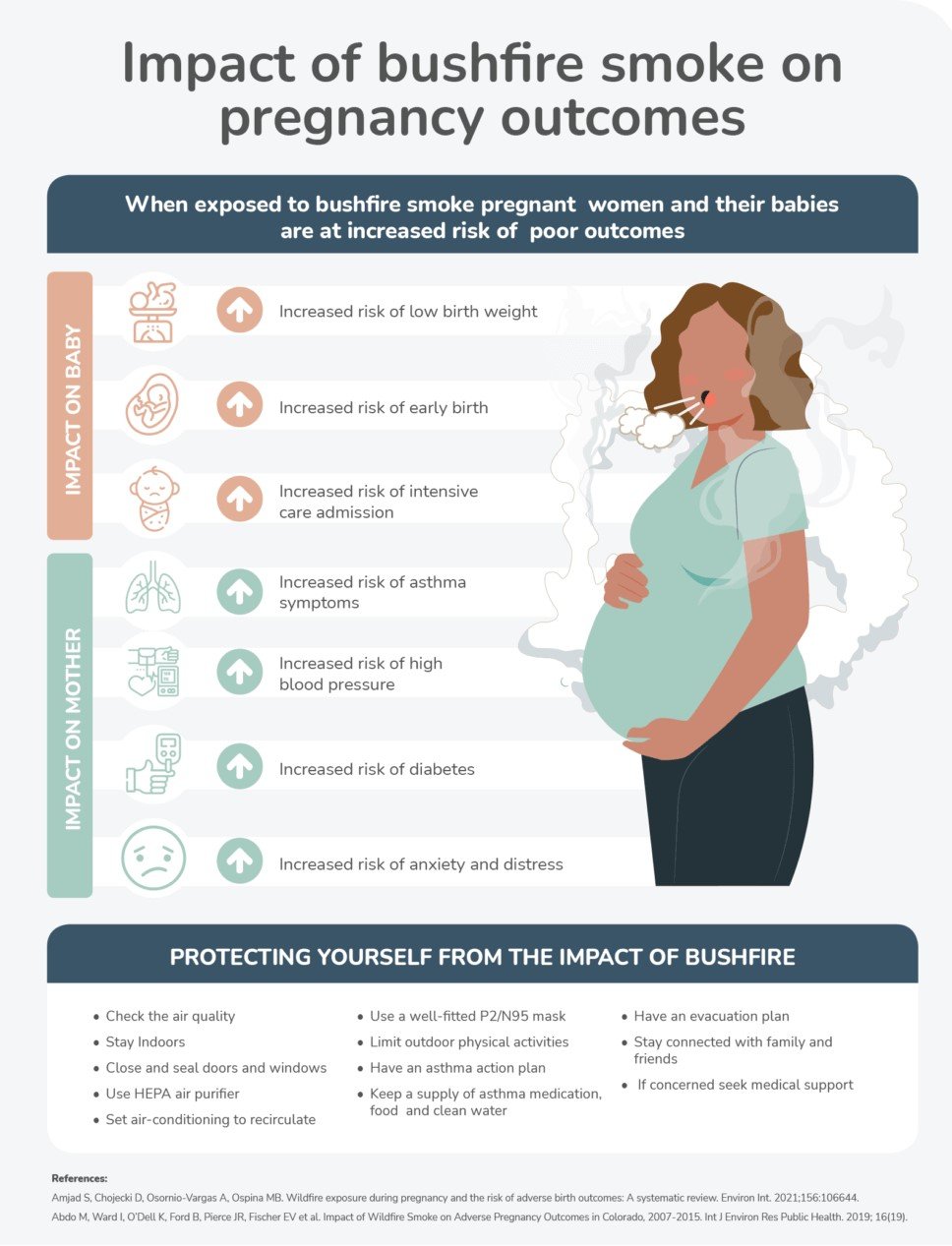

During the 2019/2020 bushfire season, public health advice was provided specifically to pregnant women on only one occasion, and women reported additional stress due to lack of knowledge about potential effects on pregnancy18. My informal review of official websites found that none gave details relevant to pregnant women, although a minority included pregnant women in lists of vulnerable groups of people. For future bushfire events, the infographic ‘Impact of bushfire smoke on pregnancy outcomes’ (pictured on page 41), developed as part of the Asthma in Pregnancy Toolkit is a valuable resource19.

There is a lot of general advice we can give women about protecting themselves from outdoor air pollution, including bushfire smoke. Possibly most important is an awareness that air pollution levels can fluctuate markedly over time and space. Apps such as Air Rater can help women plan when it is safe to go out and when to stay inside. When levels of outdoor air pollution are high, women should stay inside with doors and windows shut and attempt to minimise sources of indoor air pollution. A ‘clean air’ room with an appropriately sized HEPA filter can help during prolonged episodes.

But no building can completely protect against air pollution, so it is important to open doors and windows again once outdoor levels have improved. If women do need to go outside, properly fitted P2 or N95 masks provide a level of protection, and staying even a block or two back from busy roads can make a significant difference. More detail can be found in the RANZCOG statement on Air Pollution in Pregnancy, available through the RANZCOG website20.

We can use our knowledge and our influence to advocate for individual women at risk of air pollution due to (for example) mouldy housing or occupational exposure. We can advocate at government level, whether local, state, or federal, for policies that address air quality control, housing availability, retention of green space, and action on climate mitigation and adaptation.

What will happen the next time I meet someone like Sarah? A National Climate Adaptation Plan is currently being developed. I hope that the RANZCOG submission to the Issues Paper21 will have raised awareness of the specific vulnerabilities of pregnant women.

I hope that climate adaptation planning will include the needs of people like Sarah. I hope I can pick up the phone and get her to a safe place.

This ‘Impact of bushfire smoke on pregnancy outcomes’ infographic was developed as part of the Asthma in Pregnancy Toolkit by Centre of Excellence Treatable Traits. Photo: Supplied by The Asthma in Pregnancy Toolkit

References

- Inside the case to prove air pollution contributed to death of nine-year-old Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah [Internet]. The Independent. 2021.

- Lelieveld J, Haines A, Burnett R, Tonne C, Klingmüller K, Münzel T, Pozzer A. Air pollution deaths attributable to fossil fuels: observational and modelling study. bmj. 2023 Nov 29;383.

- Wang W, Mu S, Yan W, Ke N, Cheng H, Ding R. Prenatal PM2. 5 exposure increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: evidence from meta-analysis of cohort studies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2023 Oct;30(48):106145-97.

- Ghosh R, Causey K, Burkart K, Wozniak S, Cohen A, Brauer M. Ambient and household PM2. 5 pollution and adverse perinatal outcomes: A meta-regression and analysis of attributable global burden for 204 countries and territories. PLoS medicine. 2021 Sep 28;18(9):e1003718.

- Zhang Y, Ye T, Yu P, Xu R, Chen G, Yu W, Song J, Guo Y, Li S. Pre-term birth and term low birth weight associated with wildfire-specific PM2. 5: a cohort study in New South Wales, Australia during 2016–2019. Environment International. 2023 Apr 1;174:107879.

- Home [Internet]. APBPA. 2020. Available from: pretermalliance.com.au

- The Benefits and Costs of U.S. Air Pollution Regulations

- World Health Organization. WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2. 5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. World Health Organization; 2021 Sep 7.

- Keswani A, Akselrod H, Anenberg SC. Health and clinical impacts of air pollution and linkages with climate change. NEJM evidence. 2022 Jun 28;1(7):EVIDra2200068.

- Fussell JC, Jauniaux E, Smith RB, Burton GJ. Ambient air pollution and adverse birth outcomes: A review of underlying mechanisms. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2024 Apr;131(5):538-50.

- Johnson NM, Hoffmann AR, Behlen JC, Lau C, Pendleton D, Harvey N, Shore R, Li Y, Chen J, Tian Y, Zhang R. Air pollution and children’s health—a review of adverse effects associated with prenatal exposure from fine to ultrafine particulate matter. Environmental health and preventive medicine. 2021 Dec;26:1-29.

- Bai W, Li Y, Niu Y, Ding Y, Yu X, Zhu B, Duan R, Duan H, Kou C, Li Y, Sun Z. Association between ambient air pollution and pregnancy complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Environmental research. 2020 June 1;185:109471.

- Gutvirtz G, Sheiner E. Airway pollution and smoking in reproductive health. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2022 Dec 1;85:81-93.

- Perera F. Pollution from fossil-fuel combustion is the leading environmental threat to global pediatric health and equity: Solutions exist. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2018 Jan;15(1):16.

- Abdo M, Ward I, O’Dell K, Ford B, Pierce JR, Fischer EV, Crooks JL. Impact of wildfire smoke on adverse pregnancy outcomes in Colorado, 2007–2015. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019 Oct;16(19):3720.

- Heft-Neal S, Driscoll A, Yang W, Shaw G, Burke M. Associations between wildfire smoke exposure during pregnancy and risk of pre-term birth in California. Environmental Research. 2022 Jan 1;203:111872.

- Mirabelli MC, Damon SA, Beavers SF, Sircar KD. Patient–provider discussions about strategies to limit air pollution exposures. American journal of preventive medicine. 2018 Aug 1;55(2):e49-52.

- Davis D, Roberts C, Williamson R, Kurz E, Barnes K, Behie AM, Aroni R, Nolan CJ, Phillips C. Opportunities for primary health care: a qualitative study of perinatal health and wellbeing during bushfire crises. Family Practice. 2023 Jun 1;40(3):458-64

- Impact of bushfire smoke on pregnancy outcomes infographic [Internet]. Asthma in Pregnancy Toolkit. [cited 2024 May 14].

- Air pollution and pregnancy [Internet]. The Royal Australian College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2022.

- Converlens – Engagement data insight platform for surveys, consultations and text [Internet]. consult.dcceew.gov.au. [cited 2024 May 14].

Leave a Reply