Pelvic floor disorders such as pelvic organ prolapse (POP), and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) are strongly associated with vaginal birth and have a significant impact on the lifetime health of a woman1. In the US alone, around 300,000 women have surgery annually to repair POP and cure SUI1. Pelvic health physiotherapy plays an important role in the pre and post operative journey of a woman undergoing gynaecological repair surgery. Mollah et al (2023) assessed trends in types and incidence of POP surgery in Australia after transvaginal polypropylene mesh was removed as first line treatment of vaginal prolapse for women2,3. There has been a 38% decline in the number of POP procedures since a peak in 2005/2006 and over the past 15 years the most common age group having surgery has increased by a decade to 65 to 74 years.

While the decline in numbers of procedures may be due to the changes in TGA recommendations regarding mesh, it is also reflective of recommendations from the evidence that maximising conservative strategies (pelvic health physiotherapy, lifestyle recommendations and the appropriate fitting of a pessary) is considered first line treatment4. Postponing surgery until around 70 years of age recognises that activity levels may have decreased in this cohort, and the woman’s general health may start to decline, and it is important not to miss the opportunity for surgery.

Conservative strategies for treating vaginal prolapse

Vaginal prolapse is common, with 50% of women who have had a vaginal delivery suffering some degree of prolapse. Only 15% will have bothersome symptoms (vaginal bulge, drag and heaviness, incomplete voiding, obstructed defaecation and sexual dysfunction) and 10-20% will go on to require repair surgery when conservative measures have failed. Up to 30% of those women who elect to have surgery may need to undergo a further repair due to failure of the surgery and recurrence of the prolapse5,6. In addition, one in three women suffer with urinary incontinence, some of which is due to SUI with or without urgency incontinence (mixed incontinence). Tahtinen et al. (2016) found there was a twofold increase in the risk of long-term SUI with vaginal delivery over caesarean section in a systematic review and meta-analysis on the long-term effects of childbirth on urinary leakage7.

Conservative strategies provided by a pelvic health physiotherapist are endorsed in the treatment guidelines (2018) outlined in Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care documents on Treatment Options for Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) and Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI), following the first recommendation of doing nothing4. Pelvic health physiotherapy is also recommended in the treatment pathway in 7th ICI for all pelvic health conditions including prolapse and SUI management8.

Pelvic health physiotherapy has often been researched through the one-dimensional prism of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). Pelvic health physiotherapy has many tools in the toolbox including PFMT, teaching patients the knack (or bracing with increased intra-abdominal pressures such as with coughing, sneezing or lifting), the importance of balancing relaxation of the pelvic floor in any exercise strengthening program, good bladder and bowel habits, correct defaecation training (position and dynamics), sexual intimacy advice and exercise modification as required.

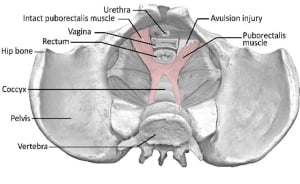

Image from Pelvic Floor Recovery: Physiotherapy for Gynaecological and Colorectal Repair Surgery 5th Edition by Sue Croft 2024

Adopting a biopsychological approach

Women have often established a close therapeutic relationship with their pelvic health physiotherapist, as they have followed this recommended approach of seeking conservative management of their POP or SUI issues as a first line of treatment. Furthermore, patients seek ongoing advice and preparation from a pelvic health physiotherapist if they are booked to have repair surgery.

However, RCT’s conducted by Nyhus (2020, 2021), Duarte (2020) and Jelovsek (2020) into pre, peri (from prior to and after surgery) and longer-term physiotherapy as a treatment intervention for gynaecological surgical repair are somewhat disappointing. Reason being, they fail to show a significant difference in outcomes of surgery with physiotherapy treatment. 9,10,11,12

These results diminish the importance of an individualised approach to treating patients and do not necessarily acknowledge the psychosocial dimension of a pelvic health physiotherapist’s consultation. In clinic, these patients are often anxious and unsure about surgery, and increasingly, pelvic health physiotherapists are adopting a biopsychosocial approach with their management pre-operatively. This helps with calming and reassuring patients that they have fully explored the conservative strategies and surgery is the logical next step. Women may also carry psychological trauma from the vaginal birth injuries that happened years before, therefore it is important to approach any education, examination, and treatment of the woman in a trauma-informed way. This often takes extended consultation time and listening to the patient about their experiences and fears.

A pre-and post-op treatment program with a physiotherapist provides a framework for the patient, with the physiotherapist playing a valuable role as a support person on this journey. Holistically supporting a woman following surgery in returning to exercise in a ‘pelvic floor friendly way’ is as equally important as achieving a good anatomical result. Over the past decade, as awareness of pelvic health conditions has grown, some women have become fearful that exercise will worsen their POP and SUI. This is partly due to advice that has blanket recommendations from health professionals and social media alike, rather than providing an ‘individualised medicine approach’ to exercise prescription for each individual woman.

If women restrict or stop exercising due to pelvic floor dysfunction, significant ramifications for their general health such as bone density depletion, poorer cardiovascular status, sarcopenia, mental health dysfunction and reduction in overall wellness may occur. If a woman is afraid to exercise following her POP repair surgery, her general health and wellbeing will suffer. Reassuring the patient that return to exercise can be modified in a safe way will help make them feel supported in their quest to return to exercise, work and sexual intimacy.

The importance of pre-operative work

With any surgery, it is always advantageous to have a pre-operative work-up prior to surgery. This helps ensure the patient is well educated about the upcoming surgery and has optimised muscle strength and tissue quality, increasing the likelihood of a good result. Assessing vaginal tissue health pre-operatively and suggesting a conversation with their GP about local oestrogen (in a post-menopausal woman), encouraging pelvic floor exercises (which also have beneficial effects on tone, blood flow and lubrication) and advising that sexual function is beneficial for good tissue quality, is all part of the physiotherapy work up.

A well-informed, well-prepared patient is always going to have a less traumatic hospital stay and a more confident recovery post-operatively than one who has had little preparation. A good pre-operative work-up by a physiotherapist also reduces the time a surgeon spends answering questions that may seem time-consuming and irrelevant to the surgeon but are important to the patient.

Pelvic health physiotherapists solve problems such as post-operative constipation, which can cause surgical failure if the patient resorts to straining to evacuate. Manipulation of products, analysis of positioning on the toilet and breathing dynamics are important preventative treatments. Performing a pre/post void bladder scan can reveal urinary retention at the pre-op visit if there is significant prolapse, and post-operatively if the patient presents with urinary frequency. Residuals of 100-150mls may be acceptable for release of the patient from hospital, but if the patient has a smaller capacity bladder, this will lead to bothersome urinary frequency. Physiotherapists can use biofeedback to teach the patient how to gain good relaxation of the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles to enhance voiding function post-op.

Many of these patients are also extremely anxious about their surgery failing and perpetually hold significant tension in these muscles, which can lead to pelvic floor muscle overactivity and myalgia as well as obstructed defaecation. Education about pelvic floor and abdominal muscle down-training is routine and pelvic health physiotherapists are well-versed in persistent pain management if post-operative surgical pain is lingering.

Image from Pelvic Floor Recovery: Physiotherapy for Gynaecological and Colorectal Repair Surgery 5th Edition by Sue Croft 2024

More recently physiotherapists have been asked by urogynaecologists to fit a small pessary post-operatively to support the surgery if the woman wishes to engage in a more vigorous post-op exercise program. Evidence tells us that the younger a patient undergoes repair surgery, the higher the risk of failure13. Fitting this small supporting pessary for exercise allows the woman to do more vigorous age-appropriate exercise, which may be advantageous for her mental health as well as her long-term fitness.

Lifting weights, whether in a gym or at home, is often perceived as risky. Pelvic health physiotherapists look at the evidence about lifting and then apply it to their patient. The factors which heighten the risk of failure for the patient’s surgical repair are increased genital hiatus size, the presence and severity of levator avulsion, collagen type, the strength of her pelvic floor muscles and the patient’s ability to contract them satisfactorily in a timely fashion and their exercise goals. The physiotherapist analyses risks and gives advice about return to lifting, employment and exercise post-operatively based on the patient’s strengths and weaknesses, while communicating closely with the surgeon.

In conclusion, gynaecological repair surgery is expensive when considering the cost of the operation, time off work and health professional appointments. There are financial, physical and mental health costs to the patient if the surgery fails. While the research may not support the routine practice of pre, peri and post operative physiotherapy, this article outlines the obvious benefits to the patient when implementing a personalised medicine approach, which will benefit the patient holistically in the long term.

About Sue Croft

Sue Croft OAM has been a physiotherapist for over 47 years, working in pelvic health for the past 36 years. Sue was awarded the Order of Australia Medal in 2023 for contributions to the community and the physiotherapy profession in pelvic health. Sue has authored three books on pelvic health physiotherapy including the recently published updated 5th Edition of Pelvic Floor Recovery: Physiotherapy for Gynaecological and Colorectal Repair Surgery.

References

- John O.L. DeLancey, Mariana Masteling, Fernanda Pipitone, Jennifer LaCross, Sara Mastrovito, James A. Ashton-Miller, (2024) Pelvic floor injury during vaginal birth is life-altering and preventable: what can we do about it? A J Obstet and Gynaecology.

- Mollah T, Brennan J (2023) Australian trends in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse in the non-mesh era. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 93: 444-447. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.17798

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016;2:CD012079e removal from the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG), and Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare documents: Treatment options for Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Treatment Options for Stress Urinary Incontinence (ACSQHC). ACSQHC: Sydney (2018)

- Brubaker, L., Maher, C., Jacquetin, B., Rajamaheswari, N., von Theobald, P., & Norton, P. (2010). Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, 16(1), 9-19. 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3181ce959c

- Wu, J. M., Matthews, C. A., Conover, M. M., Pate, V., & Jonsson Funk, M. (2014). Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 123(6), 1201-1206. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286

- Tahtinen RM, Cartwright R, Tsui JF, Aaltonen RL, Aoki Y, Cardenas JL, et al. (2016) Long-term Impact of Mode of Delivery on Stress Urinary Incontinence and Urgency Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol.70(1):148-58.

- Cardozo L, Rovner E, Wagg A, Wein A, Abrams P. (2023) Incontinence 7th Edition

- Nyhus M, Mathew S, Salvesen O, Stafno K, Volleyhaug I (2020) Effect of preoperative pelvic floor muscles training on pelvic floor muscle contraction and symptomatic and anatomical pelvic organ prolapse after surgery: randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 56 (21) 28-36

- Mathew S, Nyhus M, Salvesen O, Stafno K, Volleyhaug I (2021) The effect of preoperative pelvic floor muscle training on urinary and colorectal-anal distress in women undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery – a randomized controlled trial. International Urogynaecology Journal, 1-8.

- Duarte T, Bo K, Brito O, Bueno S, Barcelos T, Bonacin M, Ferreira C (2020) Perioperative pelvic floor muscle training did not improve outcomes in women undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Physiotherapy 66(1), 27-32

- Jelovsek J, Barber M, Brubaker L, Norton P, Gantz M, Richter H, Meikle s (2018) Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioural therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized controlled trial Jama 319(15) 1554-1565

- Cardozo L, Rovner E, Wagg A, Wein A, Abrams P. (2023) Incontinence 7th Edition

Leave a Reply