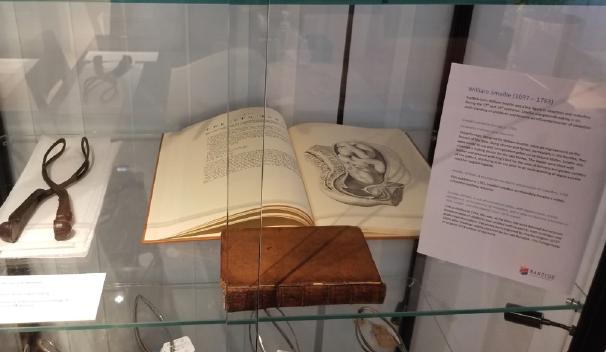

RANZCOG is particularly fortunate to hold a set of original Smellie obstetric forceps, circa 1752. The forceps were gifted to the College in 1956 by Professor Sir Lance Townsend, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Melbourne, who himself received them as part of a small collection of historic forceps that were given to him by Professor Robert Keller, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Edinburgh. Made of iron, the handles of the forceps have a sheet metal coating, and the entire instrument would have originally been covered in leather, though now only traces remain. For many years the forceps were on display in College House in East Melbourne with an accompanying explanation of their provenance and uses.

Obstetric forceps have been around for about 500 years and are said to have saved more lives than any other medical instrument. This is because they could deliver the baby when a woman was in obstructed labour – a problem which, for thousands of years, had no safe solution.

In the Middle Ages, Arab physicians had invented instruments for managing difficult births, but all these had projecting points or hooks that were pushed through the baby’s skull via the vagina, so that the infant, if not already dead, died during delivery, and mothers were also often injured.

Alternatively, if a doctor or midwife could succeed in putting a hand into the uterus and turning a cephalic presentation to a breech (all of course without the aid of anaesthetic), a hook might be inserted below the occiput and used to deliver the aftercoming head – with the same results for baby and mother. The invention of an instrument that could be easily inserted vaginally, deliver a live baby, and with less damage to the mother was therefore an enormous advance.

The obstetric forceps were originally devised by the Chamberlen family and, although many variations have appeared over the years, the basic principles of the instrument are unchanged from the Chamberlens’ original prototype.

The Chamberlens were French Huguenot Protestants who fled the 16th century pogroms of Catholic France for England, where Dr William Chamberlen established himself as an obstetrician in 1569. William had five children, of whom two were doctors, both named Peter. Peter the Younger had a son, who was also named (yes!) Peter. Peter the Third (‘Dr Peter’) then had a son named… Hugh who, in turn, had a son named Hugh.

Along with other members of the family, all three Peters and both Hughs practiced obstetrics extensively – and were among the first ‘man midwives’ of the 16th and 17th centuries. Between them they managed to keep the design of their forceps secret for more than one hundred years. They achieved this by arriving at the labouring woman’s house with the forceps concealed in a velvet-lined box, sending all possible onlookers out of the bed-chamber, and performing the delivery with the blankets covering their heads and the bedsheets tied about their necks. As women at the time lay on deep feather beds the application of the forceps was a skill that took some acquiring, and one largely achieved by touch rather than sight.

We know what the original Chamberlen instruments looked like because in 1813 some of them were discovered in Essex, UK. Found beneath the floor of the house in which ‘Dr Peter’ had died some 130 years earlier, these are now displayed in the Museum of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in London. The find consisted of four pairs of forceps, one crudely constructed, probably experimental, and probably the work of the older of the first two Peters, as well as three others, each with some improvement on the first. The concept of two blades separately applied but fitting together to form a single instrument was present from the beginning. The Chamberlen instrument was very successful and family members travelled across England, bringing relief to women in obstructed labour – as well as considerable financial benefits to themselves.

By the early 18th century the design of the Chamberlen forceps had leaked out, and soon the instrument was in use by obstetricians throughout Britain, Europe and America. In 1733 the English obstetrician Edmund Chapman wrote that “…as to the forceps, it is a noble instrument, to which many now living owe their lives.” Throughout the 1700s there were efforts to improve forceps design in order to lessen damage to mother and baby.

William Smellie (1697-1763) was a Scottish physician and obstetrician who practised and taught mostly in London, and whose skill at the management of obstructed labour was recognised throughout Britain. Smellie introduced a pelvic curve to the forceps blades, and to make the application of his instrument more comfortable for the mother he covered the metal with leather and greased it with lard before each application. He was also the first to record the use of the forceps to rotate the head before delivery and for the aftercoming head of a breech.

Up until the end of the 19th century, forceps were only ever used for prolonged or obstructed labour. In 1920, the American obstetrician Joseph De Lee proposed the use of forceps delivery ‘prophylactically’ to ‘spare’ the mother and infant the effects of long labour. This further led to the idea of proceeding to a forceps delivery when there was fetal distress – diagnosable then only by use of the Pinard horn to detect slowing of the fetal heartrate. This was a truly revolutionary idea. By the last decades of the 20th century forceps delivery was widely used for a variety of indications, often along with epidural analgesia and fetal monitoring – with the latter two, suggested by some, to be a direct cause of increased forceps rates.

What role, if any, do forceps have in 2023? We have a national caesarean rate of more than 30%, and widespread use of the vacuum extractor, which itself has undergone many modifications and improvements in recent years. Along with this is a fundamental belief in obstetric practice that, in the words of London obstetrician Peter Huntingford: “…there are now only two routes of birth: easy vaginal delivery, and caesarean section.”

Added to this is the fact that those of us who trained in the latter decades of the 20th century, when forceps delivery, including mid-cavity, was widely practised, are now retiring. Adequate training of our younger colleagues, particularly in the safe use of rotational forceps, has become problematic due to fewer cases available and reduced working hours. Training and competence in the use of mid-cavity rotational forceps is likely to become more and more inadequate. Increasingly, I believe, we will see less use of forceps in this situation, and increasing use of emergency caesarean section without a prior attempt at operative vaginal delivery.

Nevertheless, I believe it is vital that trainees and younger obstetricians understand the hugely important role that forceps played in the practice of obstetrics over five centuries. Efforts to reduce the mortality and morbidity of childbirth – through continuing innovations and designs and increasing indications for forceps application – have succeeded in the production of an effective yet quite simple instrument.

The Smellie forceps are currently on display at Djeembana College Place in Naarm Melbourne, alongside a selection of other historic forceps. Members and trainees are invited to visit the College to view this important piece of obstetrics history.

Leave a Reply