Perineal trauma is sustained in over 85% of all who have a vaginal birth. Maternal birth injury has been rising over the past three decades in New Zealand. Reasons for this rise are multifactorial including: increased recognition, improved training in perineal trauma assessment, changing demographics of pregnant women with increasing maternal age, ethnic diversity, larger babies and changes in obstetric practices.

Over this time, a greater understanding has allowed us to identify those with risk factors who are most at risk of perineal trauma, implement preventive strategies to reduce perineal trauma, both in the index delivery and in future deliveries, to minimise further physical trauma with a recurrent anal sphincter injury and psychological harm and regret.

The classification of perineal trauma was initially described by Dr Abdul Sultan in 1999,1 and has been widely adopted internationally:

- First-degree tear: Injury to perineal skin and/or vaginal mucosa.

- Second-degree tear: Injury to perineum involving perineal muscles but not involving the anal sphincter.

- Third-degree tear: Injury to perineum involving the anal sphincter complex:

- Grade 3a tear: Less than 50% of external anal sphincter (EAS) thickness torn.

- Grade 3b tear: More than 50% of EAS thickness torn.

- Grade 3c tear: Both EAS and internal anal sphincter (IAS) torn.

- Fourth-degree tear: Injury to perineum involving the anal sphincter complex (EAS and IAS) and anorectal mucosa.

Following delivery, recognition and repair of an obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) and appropriate follow up is essential. It is important to address both

physical and psychological trauma.

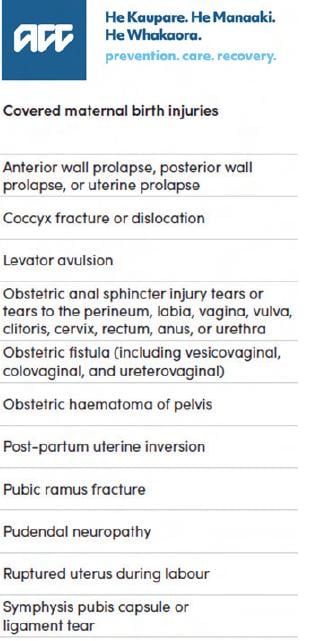

Significant progress has recently been made in New Zealand with changes in legislation. Accident Compensation (ACC) is a Crown entity that provides aid with health, rehabilitation and service provision to any New Zealander or visitor to New Zealand who has sustained an injury. From 1 October 2022, ACC recognised maternal birth trauma as an injury and cover is now available automatically for all birth parents who meet the criteria (see below). This includes early access to pelvic floor physiotherapy, referral to specialists if necessary, psychological support and home help.

The postpartum period is defined by ICS/IUGA terminology paper ‘from delivery to 12 months after delivery’, recognising the longevity of pelvic floor healing over this time.2

Management of subsequent pregnancies: what do we know and what questions remain unanswered?

Ideally follow up after severe perineal trauma should be in a dedicated multidisciplinary setting, with an obstetrician/gynaecologist or urogynaecologist with a special interest in obstetric trauma and a women’s health physiotherapist, with colorectal input.

Concerns for birth parents with a history of OASI include the risk of recurrence of an anal sphincter injury and the risk of worsening anal incontinence. Individualising care is imperative, addressing clinical symptoms and unfortunately few places in New Zealand routinely offer adjuvant imaging, either transperineal ultrasound (TPUS), endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) or anal manometry (AM), to assist with planning future pregnancies. Given these limitations, how can we counsel women adequately?

Clinical symptoms are poorly predictive at identifying structural integrity of the anal sphincter complex. A metanalysis in 2020 by M Sideris et al, showed that following primary repair, 55% had a persistent sphincter defect, with 38% experiencing anal incontinence. Of concern, in the group of women without clinical suspicion of OASI, 13% had a defect on EAUS and 14% experienced anal incontinence.3 Vigilance is therefore necessary when giving advice regarding mode of delivery with any birth parent who has had a previous vaginal delivery, as a missed OASI may have been sustained. When symptoms are compared with grade of tear, those that have sustained a 3C and fourth degree tear have a significantly higher rate of anal incontinence compared to those with a 3A tear.4

A study in 2020 by A Taithongchai et al reviewed 74 patients with fourth degree tears. 61% were asymptomatic. Endoanal scanning identified an internal anal sphincter defect in 77% and external anal sphincter defect in 49%. This confirms the presence of symptoms alone are poorly predictive of a sphincter defect. Based on RCOG guidance, in this cohort of patients only 7% would be offered a vaginal birth, i.e. asymptomatic with a normal scan and manometry findings. When imaging is not possible, birth parents with major OASI injuries (3c/4th degree trauma) should be offered an elective caesarean section.5

Croyden University Hospital share 11 years of their experience running a perineal tear clinic, which provides useful guidance for our setting. Their clinics would include:6

- A detailed history including demographic data (age, parity, ethnicity), mode of delivery, obstetric details, degree of perineal trauma, and presence of vaginal, urinary and bowel symptoms. Severity of anal incontinence was assessed using the validated modified St. Mark’s incontinence score. Urinary incontinence was assessed using the validated International Consultation on Incontinence modular Questionnaire for Incontinence-Short Form (ICIQ-UI_SF).

- A vaginal examination to assess wound integrity, size of the perineal body (cm) and pelvic floor muscle contraction using the Modified Oxford Scale.

- Appropriate investigations such as anal manometry (AM) and endoanal ultrasound scan (EAUS). These were performed in all women with a history of OASIs.

Risk of recurrence of OASI

In a multi-centre retrospective cohort study of 2,272 women with a history of OASIS, 10% suffered a recurrent OASI. Positive predictors for the risk of recurrence included increased birth weight and maternal age at both the index and subsequent delivery, a more severe degree of initial OASI and Asian ethnicity. Of particular note, a mediolateral episiotomy (MLE) rate of 15% was recorded in subsequent deliveries, and 77% of those who had an episiotomy sustained no additional perineal trauma. MLE decreased the risk of recurrence of OASI by 80%, suggesting a more liberal use of mediolateral episiotomy in women with a history of OASI could significantly reduce the risk of recurrence.7

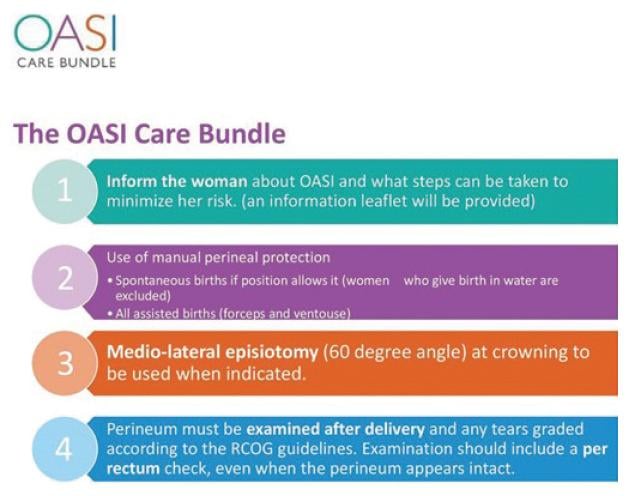

Numerous prevention models internationally have been initiated since the early 2000s, following Norway’s intervention program that showed OASI rates could be reduced with preventative strategies. UK’s OASI care bundle includes antenatal discussion about OASI, manual perineal protection, mediolateral episiotomy at 60° from the midline, and systematic examination of the perineum, vagina and anorectum after vaginal birth. Australia’s ‘Please Squeeze’ has also been shown to reduce maternal birth trauma.8,9

To date, there have not been any predictive models to specifically identify women at risk of OASI; however, birth parents who sustain OASI are at risk of pelvic floor dysfunction and many are familiar with UR-CHOICE, a predictive model identifying women with a risk of future pelvic floor dysfunction. This scoring system is based on several major risk factors (urinary incontinence before pregnancy, ethnicity, age at birth of first baby, BMI, family history of pelvic floor dysfunction, baby’s weight and maternal height). This model is based on moderately robust epidemiological data at 12 and 20 years after delivery.10 It may be a useful adjuvant during the counselling process, but caution should be used when counselling a birth parent with a maternal age above 34, as the risk assessment tool has no comparable data.

In conclusion, when counselling birth parents who have sustained an OASI injury, an awareness of the limitations when using a risk-based or symptom-based approach is imperative. Birth parents who are symptomatic of anal incontinence and those with major 3c and fourth degree tears should be offered an elective caesarean section. Individualising care for those women with 3A and 3B tears remains the recommendation regarding subsequent mode of delivery. Birth parents who, after adequate counselling, choose a vaginal delivery will benefit from preventative strategies at delivery. Consideration of a mediolateral episiotomy, manual perineal protection, choosing a ventouse over forceps if an assisted delivery is required and an early recourse to caesarean section if an obstructed labour is anticipated are all important elements to discuss. With a shared decision-making process, regret in the longer term can be minimised.

References

- RCOG Green top guideline: Third and Fourth degree tears, management 2015

- Doumouchtsis S, et al. An international Continence Society (ICS)/ International Urogynaecological Association(IUGA) joint report on the terminology for the assessment and management of obstetric pelvic floor disorders. IUJ. 2023;34,1-42.

- Sideris M, et al. Risk of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) and anal incontinence: A meta-analysis. Euro. J. Obstet Gynaecol. June 26, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.06.048

- Okeahialam N, et al. The incidence of anal incontinence following obstetric anal sphincter injury graded using the Sultan classification: a network meta-anaylsis. Am J O&G. Nov 2022.

- Taithingchai A, Thakar R, Sultan A. Management of subsequent pregnancies following fourth-degree obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS). Euro. J. Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;250:80-5.

- Wan O, et al. A one-stop perineal clinic: our eleven-year experience. IUJ. 2020;31:2317-26.

- D’Souza J, et al. Maternal outcomes in subsequent delivery after previous obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI): a multi-centre retrospective cohort study. IUJ. 2020;31:627-33.

- Jurczuk M, et al. The OASI care bundle quality improvement project: lessons learnt and future direction. IUJ. 2021;32:1989- 95.

- Luxford E, et al. ‘Please Squeeze’: A novel approach to perineal guarding at the time of delivery reduced rates of obstetric anal sphincter injury in an Australian tertiary hospital. https://doi. org/10.1111/ajo.13181

- Wilson D, et al. UR-CHOICE: can we provide mothers-to-be with information about the risk of future pelvic floor dysfunction? IUJ. 2014;25:1449-52.

Leave a Reply