A 30-year-old para 2 with a medical history of two previous caesareans, migraine with aura, hyperthyroidism, essential hypertension, anxiety and depression and a BMI of 33 presented to primary care with sudden onset abdominal pain.

She had a Mirena intrauterine device (IUD) inserted in primary care two years prior for contraception. She was amenorrhoeic with this and had no immediate complications following insertion.

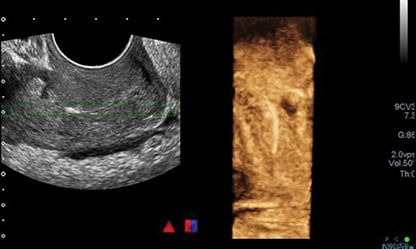

Blood work on acute presentation was notable for a white cell count of 17.9, neutrophils of 15.4, and CRP 138. A pelvic ultrasound scan showed a linear, echogenic structure within the endocervical canal, likely reflecting a malpositioned IUD.

Figure 1. Initial ultrasound scan reported as ‘linear echogenic structure within the endocervical canal that may reflect a malpositioned IUD.’

The same day, she was referred to the acute gynaecology unit where the Mirena strings were seen on speculum examination. However, the Mirena was unable to be retrieved with routine traction on the strings, which snapped. She therefore underwent diagnostic hysteroscopy under general anaesthesia.

On hysteroscopy, the Mirena was not clearly visualised, but the stem was reported to be seen buried within the right posterior aspect of the endocervical canal, halfway between the external and internal os. It was felt that this suggested the Mirena was buried into a false passage on insertion, perforating the cervix and therefore at risk of being partially intra-abdominal and in proximity to the bowel. At this time, a Jadelle contraceptive implant was inserted.

Two days later a diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. Normal pelvic anatomy was noted. Omental adhesions to the anterior abdominal wall were divided and a small amount of blood was seen in the pelvis, which was felt to be associated with a ruptured corpus luteum on the left ovary. This was the likely cause of the patient’s presenting pain, which by now was improving.

The Mirena was unable to be located in the peritoneal cavity. Hysteroscopy was repeated and revealed an empty uterus. The Mirena stem that was previously seen in the canal was now no longer visible. A bedside transvaginal ultrasound could not identify the Mirena.

Assistance from the general surgical and interventional radiology teams was requested but the Mirena was still unable to be located despite a thorough search of the entire abdomen. On X-ray, the Mirena was thought to be seen in the right iliac fossa, perhaps buried in the myometrium

or parametrium.

A CT was requested to further delineate the location of the Mirena. This showed the Mirena outside the uterus, between the right ovary and right internal iliac vessels, appearing retroperitoneal and deep to the round ligament.

Figure 2. CT abdomen with report stating ‘the Mirena coil is situated outside the uterus, between the right ovary and internal iliac vessels. Appears retroperitoneal and deep to the round ligament.’

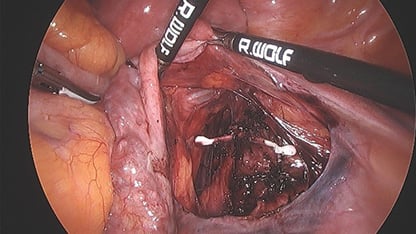

Opinion was sought from the gynaecology oncology team given the proximity to the iliac vessels. As future further invasion of surrounding tissues could not be excluded, and the patient desired removal of the Mirena, she again underwent laparoscopy with assistance from the gynaecology oncology team. The right fossa was opened underneath the round ligament. The Mirena was then visualised overlying the iliac vein. It was noted to be peritonealised with surrounding adhesions, giving the impression that it had been there for a prolonged period.

The Mirena was dissected and removed in entirety; however, no strings were attached consistent with the history of the strings having been pulled off at the initial removal attempt. The patient made an unremarkable recovery.

Figure 3. Mirena located in overlying the iliac vessels at laparoscopy.

Discussion

Intrauterine contraception is used by 160 million women, or 14% of contraceptive users worldwide.1 The Mirena IUD was introduced in 1990.2 In the NZ Family Planning survey 2020, 19% of responders had previously or were currently using a Mirena IUD.3

Perforation of an IUD was first described in the 1930s4 and was thought to be caused by forcing of the device through the uterine wall by contractions. It is now accepted that the most common mechanism of perforation is the device being forced through the uterine wall on insertion.5

Associations between risk factors and uterine perforation are difficult to demonstrate but are thought to include:6 7

- Insertion by inexperienced clinician

- Lactation

- Insertion <6 months postpartum

- Lower parity

- Higher number of previous abortions

In 90% of cases, perforation is not recognised at the time of IUD insertion.8 In a 10-year New Zealand cohort study, over half of perforations were diagnosed over one year after insertion.9 The threads are generally still emerging from the cervical os at the end of the procedure, even with complete perforation.10 This is consistent with the history of strings being seen on our patient’s initial speculum examination.

The discrepancies between clinical findings and that of various modalities of imaging on multiple occasions lead to significant morbidity for our patient, undergoing three general anaesthetic procedures within a few months. One series reported a significant discrepancy between the location of IUDs indicated by USS imaging and subsequent location at surgery.11 CT and MRI are the most accurate imaging modality for localisation.12 However, in comparison, ultrasound is safe, easily accessible, and cheap. The Mirena IUD has a different ultrasound appearance to copper devices as it is not uniformly hyperechoic and has acoustic shadowing only at its proximal and distal ends.13 This sonographic appearance leads to higher rates of localisation errors with ultrasound.

Whether laparoscopic removal was indicated is also a relevant thought. The patient had no desire for future fertility, and in fact had not conceived for two years while using the Mirena as her only form of contraception, likely due to the local progesterone effect. In fact, it is not unusual to hear of IUDs found intra-abdominally many years after their original insertion, with one case series reporting 43 years between insertion and diagnosis of perforation.14 However, case reports have shown that migration in the peritoneal cavity can result in bowel obstruction, bowel perforation, mesentery penetration, abscess formation, intestinal ischaemia or volvulus.15 16

Therefore, some clinicians recommend that displaced IUDs should always be removed to prevent complications due to intraperitoneal adhesion formation or migration to adjacent organs. However, some deem the risks of surgery and anaesthesia greater than the risk of migration.17 18 The risk of adhesions is thought to be greatest with copper IUDs; therefore, those made of non-irritating plastic, such as the Mirena, may be at lower risk of this.19

The decision to remove the IUD should therefore involve careful consideration of the risks of surgery compared to the risks of conservative management, while also considering the patient’s wishes, fertility plans and psychological wellbeing with regards to their awareness of an intra-abdominal foreign body.

The small risk of IUD perforation can at times lead to significant diagnostic challenges and patient morbidity. We propose that consideration should be given to routine ultrasound at the bedside following insertion to confirm IUD location, but the feasibility and cost effectiveness of this in New Zealand’s current health system requires investigation.

Drs Whitaker and Coolem work in the Department of O&G at Christchurch Women’s Hospital, Canterbury District Health Board.

References

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kubba A, Caetano C, Faustmann T, Lukkari-Lax E, Heikinheimo O. Thirty years of Mirena: a story of innovation and change in women’s healthcare. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Scand. 2021;100:614–8.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kubba A, Caetano C, Faustmann T, Lukkari-Lax E, Heikinheimo O. Thirty years of Mirena: a story of innovation and change in women’s healthcare. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Scand. 2021;100:614–8.

- NZ Family Planning. Contraception use survey 2020. October 6th 2020. [cited February 2022]. Available from: https://www.familyplanning.org.nz/news/2020/contraception-use-survey-2020.

- Murphy MC. Migration of a Grafenberg ring. Lancet. 1933;2:1369–70.

- Rowlands S, Oloto E, Horwell DH. Intrauterine devices and risk of uterine perforation: current perspectives. Open Access J Contracept. 2016;7:19–32.

- Rowlands S, Oloto E, Horwell DH. Intrauterine devices and risk of uterine perforation: current perspectives. Open Access J Contracept. 2016;7:19–32.

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Guidance. Intrauterine Contraception. FSRH. 2015 (amended September 2019).

- Harrison-Woolrych M, Ashton J, Coulter D. Uterine perforation on intrauterine device insertion: is the incidence higher than previously reported? Contraception. 2003;67:53–6.

- Harrison-Woolrych M, Ashton J, Coulter D. Uterine perforation on intrauterine device insertion: is the incidence higher than previously reported? Contraception. 2003;67:53–6.

- Rowlands S, Oloto E, Horwell DH. Intrauterine devices and risk of uterine perforation: current perspectives. Open Access J Contracept. 2016;7:19–32.

- Nitke S, Rabinerson D, Dekel A, Sheiner E, Kaplan B, Hackmon R. Lost levonorgestrel IUD: diagnosis and therapy. Contraception. 2004;69:289–93.

- Rowlands S, Oloto E, Horwell DH. Intrauterine devices and risk of uterine perforation: current perspectives. Open Access J Contracept. 2016;7:19–32.

- Gowri V, Mathew M. Ultrasound location of misplaced levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system – it is easy? Oman Med J. 2009;24:54–5.

- Kho KA, Chamsy DJ. Perforated intraperitoneal intrauterine contraceptive devices: diagnosis, management and clinical outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynaecol. 2014;21:596–601.

- Ozgun MT, Batukan C, Serin IS, Ozcelik B, Basbug M, Dolanbay M. Surgical management of intra-abdominal mislocated intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2007;75:96–100.

- Gill RS, Mok D, Hudson M, Shi X, Birch DW, Karmali S. Laparoscopic removal of an intra-abdominal intrauterine device: case and systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85:15–8.

- Markovitch O, Klein Z, Gidoni Y, Holzinger M, Beyth Y. Extrauterine mislocated IUD: is surgical removal mandatory? Contraception. 2002;66:105–8.

- Adoni A, Ben Chetrit A. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43:77–81.

- Adoni A, Ben Chetrit A. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43:77–81.

Leave a Reply