“The only reason you got into medical school is because you are Māori.” I have heard it muttered around friends, said to others, and received the comment to my face, not once, but several times throughout undergraduate medical training. I’ve had similar messages inferred in specialist training too. ‘Friends’ asked, “why do Māori get in above me when I have the same or higher grades?” Justifying their remarks that I don’t deserve my position because being Māori holds no value, certainly not above anyone else’s culture. And we all care, so the ‘best’ people should be doctors, and no special allowances should be made. My question was: best for who?

Ko Maungatere te maunga

Ko Tākitimu te waka

Ko Rakahuri te awa

Ko Ngāi Tahu te iwi

Ko Ngāi Tūāhuriri te hapū

Ko Mahuunui II te marae

Ko Sarah Te Whaiti tōku ingoa

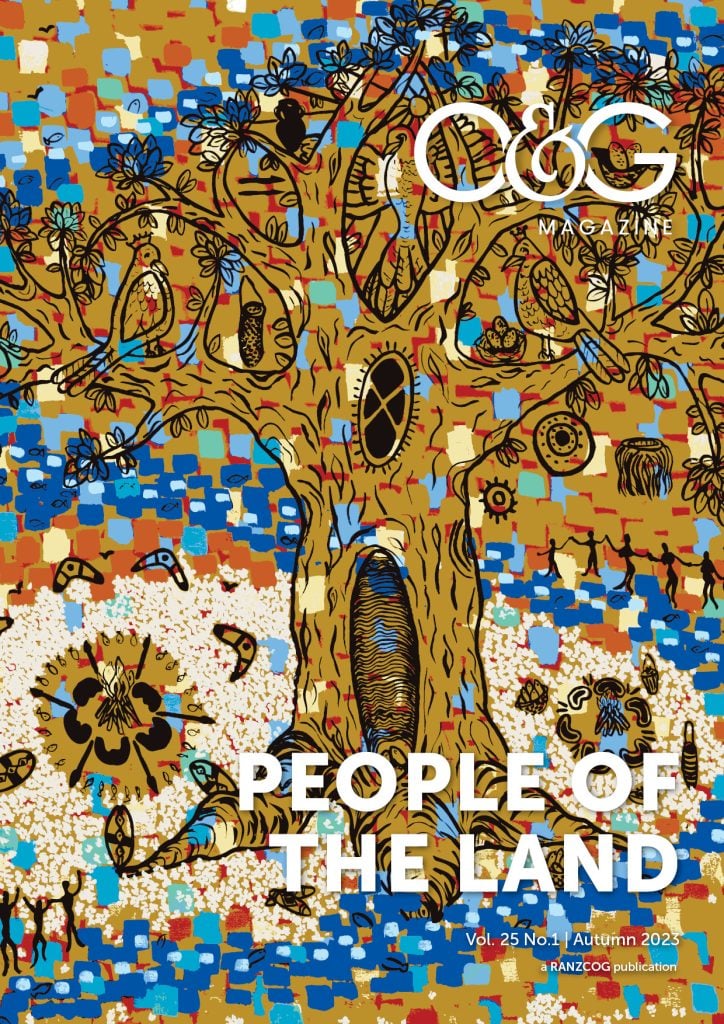

My pepeha above explains that Maungatere is the mountain below which my ancestors settled. Tākitimu is the canoe my ancestors used to intentionally traverse the Pacific Ocean hundreds of years ago. Rakahuri is the Ashley River, the water source that has provided life to my people for generations. Ngāi Tahu is the collective name of my tribe, and Ngāi Tūāhuriri my subtribe. Mahuunui is our meeting house where people gather to celebrate, discuss matters of importance, and mourn our dead. I am Sarah Te Whaiti, and my lineage makes me tangata whenua, a person of the land. In particular, I am a person of my ancestral lands in Te Waipounamu (the South Island of New Zealand).

As tangata whenua, you not only come from your specific land but also belong to it; you are a part of it. Your environment begat you. The mountain is an ancestor, likewise, the river and the rest of the environment are part of your genealogy. They give you strength, prosperity and authority in your region, and you owe them your existence, strength, prosperity, and mana. The reciprocal relationship is a state of being, ensuring both parties are looked after for future generations. This philosophy of connectedness extends to your iwi and community. Your whakapapa (genealogy) tells you who you are, who you are connected to, and what role you have within the community. These connections and relationships span generations. You are your ancestors’ realities and hopes unfolding, and your mokopuna (grandchildren) will be yours. This interconnectedness and responsibility to people and place are what being tangata whenua means to me.

I didn’t always know that about myself. I didn’t grow up in my ancestral lands. I was born and raised in Wellington by a young pakeha (non-Māori) mother. Mum invested in my culture; she sent me to a bilingual unit in a mainstream school, anticipating my desire to be in a Māori environment she couldn’t provide herself. My dad moved back to Christchurch, and although he too was disconnected from our iwi and wider whānau, it was through him being back in our ancestral home that our reconnections began. Dad found out about our whakapapa, got in touch with an aunty and, from there, he could link me to our whānau. Over the years, I visited and built relationships. Inadvertently I was opening the wounds of broken relationships, migration, racism and hurt I didn’t understand. Yet throughout these years of discovery, I began reconnecting to the depth of who we are and where we belong as Māori.

Sadly, my experience is not unique. The impact of colonisation has been long-lasting, diverse and painful. While some Māori faced land confiscation through force and war, others, like my people, Ngāi Tahu were coerced into unfair land sales.1 The consequences of these sales were displacement, disconnection from whenua (land), whānau (family), and culture.2 The Crown’s actions also aimed to stifle the language.3 It was beaten from our ancestors’ mouths and marked down for extinction. The Crown also reneged on building promised roads, schools, and hospitals, entrenching inequity for our people. The colonial agenda repeatedly undermined Māori, undermined Māori ideas and ways of doing things, tried to sabotage our successes, and dismissed our claims, entitlements and right to self-determination. The expectation was that Māori would assimilate to be British as if it was superior.4 Another question: Why was one better than another? What was this based on?

I see the distrust, confusion and hurt continue in many Māori patients. The hospital and its systems weren’t built in a Māori friendly way or even with Māori in mind. Many Māori find the environment intimidating, and threatening, a place people go and don’t come back from. So, it’s hard for Māori to believe that people within the hospital really want to help, want to change things for the better and can offer support. In the thinking of Māori we ask, why? Why trust this? Why trust these institutions when history repeatedly taught us not to?

Some ask me what’s it like to be a Māori trainee/doctor. The truth is more complex than the answer, “It’s a tough, demanding, but rewarding responsibility.” I have experienced excitement, fulfilment and joy as I have had consultations with women in te reo Māori. If you see a familiar face in a hospital, share a language, share tikanga (customs) and share similar experiences of intergenerational trauma and distrust, you forge a unique relationship. Together, we face the hospital system and its biases, inequity and hostility and make it a little safer for one another. I’ve had patients thank me for being there. Some patients have waited in clinic to see me because they feel culturally safe and medically acknowledged. I’ve been humbled to have had patients ask me to welcome their newborn pēpi (baby) into the world using te reo Māori, to ensure Māori was the first language heard.

My experience is that being recognisably Māori helps. Both medical schools, the University of Otago and The University of Auckland faculties of medicine recognised their responsibility to better reflect New Zealand’s society in their medical enrolments.5 6 The policies of the university admissions schemes began to change in the 1990s to prioritise entry of certain groups and rectify the medical fraternity to be a fair representation of society. There is clear evidence that people from different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to serve their own populations.7 This service leads to better health outcomes for diverse populations. To better care for, that is, to reduce the inequity faced by Māori, Pacific, rural and now refugee and lower socioeconomic people, students from these backgrounds need priority entry.

Today we have more Māori doctors than we ever have had. But still, it is probably not enough. We know that our demographics are changing in New Zealand, and by 2050, Māori, Pasifika, and Asian will make up most of our population. So, what’s the next step? We need to keep encouraging more Māori into the system and supporting them when they start to follow speciality training. I hope RANZCOG and other training programs find ways to put more value on what the Māori workforce brings to our people. I hope people’s commitment to learning te reo Māori and connection to their whakapapa is rewarded. I hope trainees can attain points towards an entry application based on their fluency in te reo Māori, and that RANZCOG facilitates paid leave for trainees and Fellows to attend language courses. I hope RANZCOG meets the responsibility many Māori feel to their community with options to train in their turangawaewae (ancestral lands). I hope the networks of Māori clinicians and He Hono Wahine are invested in, because these groups effectively support our Māori clinicians with understanding, empathy and care. The time has come for our medical fraternity to take these brave moves forwards to keep our healthcare relevant to and fit for our communities. Let us value our patients and our workforce and change the design of our system to provide better care for future generations.

Sarah with her future generation: Te Ukiihikitia (left) and Te Rauhuia (right)

Our feature articles represent the views of our authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), who publish O&G Magazine. While we make every effort to ensure that the information we share is accurate, we welcome any comments, suggestions or correction of errors in our comments section below, or by emailing the editor at [email protected]. Those pictured have provided consent for their name and image to be included.

References

- Ian Pool, ‘Death rates and life expectancy – Effects of colonisation on Māori’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/death-rates-and-life-expectancy/page-4.

- Ian Pool, ‘Death rates and life expectancy – Effects of colonisation on Māori’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/death-rates-and-life-expectancy/page-4.

- Ka’ai-Mahuta, R. The impact of colonisation on te reo Māori: A critical review of the State education system. Te Kaharoa. 2011;4(1). https://ojs.aut.ac.nz/te-kaharoa/index.php/tekaharoa/article/view/117

- Ka’ai-Mahuta, R. The impact of colonisation on te reo Māori: A critical review of the State education system. Te Kaharoa. 2011;4(1). https://ojs.aut.ac.nz/te-kaharoa/index.php/tekaharoa/article/view/117

- MAPAS The story of the Māori and Pacific Island admissions scheme from 1972. https://fmhs-history.blogs.auckland.ac.nz/mapas/#:~:text=The%20first%20student%20admitted %20in,Henry%20Bennett%20was%20medical%20superintendent.

- Crampton P, Weaver N, Howard A. Holding a mirror to society? Progression towards achieving better sociodemographic representation among University of Otago health professional students. NZMJ. 2018;131:1476.

- Crampton P, Weaver N, Howard A. Holding a mirror to society? Progression towards achieving better sociodemographic representation among University of Otago health professional students. NZMJ. 2018;131:1476.

Leave a Reply