For the broader O&G Magazine readership, Q&A seeks balanced answers to those curly-yet-common questions in obstetrics and gynaecology.

How do I support my patients in self-collection for the National Cervical Screening Program?

On 1 July 2022, a major policy change supporting the informed choice of either self-collection of a vaginal swab or a clinician-collected cervical sample for primary human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was implemented within the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP). This change, grounded in improving access and equity, was announced on 8 November 2021 by then Minister for Health and Aged Care, Greg Hunt, following recommendations from the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) after detailed review of the evidence around the accuracy and acceptability of self-collection.1

The shift in 2017 from 2-yearly Pap tests to 5-yearly HPV testing in the NCSP, and the national school-based HPV vaccination program for 12- to 13- year-old girls and later boys, have put Australia on track to be the first country in the world to reach the World Health Organisation (WHO) cervical cancer elimination target of fewer than 4 cases per 100,000 women as early as 2028 to 2035.2 3 However, while cervical cancer was the 14th most common cancer in females in 2020 there were still approximately 743 new diagnoses in 2017 and 179 deaths in 2019 in women between 25 and 74 years of age, with almost three-quarters of deaths occurring amongst those who are under or never-screened.4

At the end of 2020 more than 30% of those eligible for screening were overdue5, with the limited available data highlighting that under and unscreened people belong to multiple and varied groups including:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who have an almost four-times greater chance of dying from cervical cancer than non-Aboriginal women

- Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) women including new migrants and refugees

- Patients with physical and/or intellectual disability

- Members of the LGBTQI+ community including transgender men

- Those with a history of sexual assault and/or who feel stigma and shame around intimate examinations

- People who experience pelvic pain including vaginismus with a speculum examination

- Patients with previous negative screening experiences

Universal self-collection is a potential gamechanger in overcoming some of the screening barriers faced by these groups, and to make the elimination goal a reality for all.

In this article we present the evidence for self-collection, review the eligibility criteria within the NCSP and provide an overview of the updated guidelines for the management of screen-detected abnormalities in the NCSP (the Guidelines) for self-collection.6 O&Gs and midwives are well placed to opportunistically offer the choice of self-collected or clinician-collected HPV sampling to under and unscreened patients, as well as to patients requiring a HPV-only test, and not a co-test, anywhere in the NCSP pathway.

Accuracy of and eligibility for self-collection

Prior to the implementation of the renewed NCSP, current evidence suggested that HPV testing of self-collected vaginal samples using available signal amplification tests was slightly less sensitive than HPV testing of clinician-collected cervical samples for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)2+.7 However, an updated meta-analysis showed equivalent accuracy of self- versus clinician-collected samples when using today’s polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests.8 Based on the earlier evidence, self-collection in the renewed NCSP was initially restricted to those who were under-screened (aged 30 years or more and 2 or more years overdue for screening), and uptake was extremely low (< 1% of those eligible9) due to a combination of lack of confidence in self-collection by clinicians, a limited number of laboratories offering processing and low awareness by clinicians and patients.10 The removal of restrictions to self-collection since 1 July 2022 is likely to see an increase in demand for self-collection, including by under-screened groups.

Self-collected vaginal samples are tested for oncogenic HPV with partial genotyping into either HPV (16 and/or 18) or one or more of the other 12 oncogenic HPV (not 16/18) types. As a self-collected sample does not collect cells from the cervix, it cannot be used for cytology, which precludes self-collection for anyone requiring a co-test. However, anyone eligible for a CST, or a HPV test alone, can be offered the choice of either a self-collected or clinician-collected sample for HPV testing. As noted, this includes antenatal patients for whom this visit may be the first time they have come in to contact with a health service and be offered screening.

Supporting informed decision-making

In order to support informed decision-making, patients must be given information about how a self-collected vaginal sample and a clinician-collected cervical sample are performed, as well as the pros and cons of each, including the need to return for a clinician-collected cytology test for most of those in whom HPV (not 16/18) is detected. Step-by-step guidance about self-collection is available from the NCSP (Figure 1) in 17 languages including six Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, and by instructional videos.11

Figure 1. Simple self-collection instructions from the National Cervical Screening Program

While previously only three pathology labs were offering processing of self-collected samples, there are now a range of HPV assays with TGA-approved claims for self-collection, and several labs now offer this service with more expected to follow. Some labs use red-topped dry flocked swabs which are sent to the lab directly for processing, whilst others use the Roche platform which requires the practitioner to agitate the dry swab collected by the patient in a liquid medium which is then sent to the lab for processing. Practitioners are encouraged to contact their local pathology service to confirm that they can process self-collected vaginal samples, or that they have an arrangement in place to send them on to another lab for processing, and to ensure they have the correct swabs, handling requirements and resources to support their patients.

Labelling the sample as self-collected and providing this information on the pathology request form is essential to ensure the lab performs the correct test and provides the correct clinical recommendations. In addition, the pathology request form should be completed with appropriate clinical and patient identification information. This includes asking and documenting whether patients identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander as this impacts on clinical management in the intermediate risk pathway.

Additionally, the National Cervical Screening Register (NCSR) supports the screening program by sending invitations and reminder letters to participants and has updated information on its Provider and Participant Portals on the option of self-collection. The NSCR Provider Portal,12 accessible to all registered practitioners via their PRODA account, is extremely useful as it allows point of care access to the patient’s screening and treatment history.

Where can self-collection occur

Universal self-collection has been introduced with the aim of bringing under and never-screened people into the NCSP. The Guidelines,13 while stating that self-collection is preferable in a health care setting as this guarantees timely return of the sample, also support clinicians in providing screening in any setting they believe is appropriate to encourage participation of an individual who may otherwise remain unscreened. This opens up the possibility of supporting screening via telehealth, through community outreach or even screening at home, although critically the requesting clinician takes complete responsibility for informing patients of their results and any required follow-up.

Self-collection clinical pathways within the NCSP

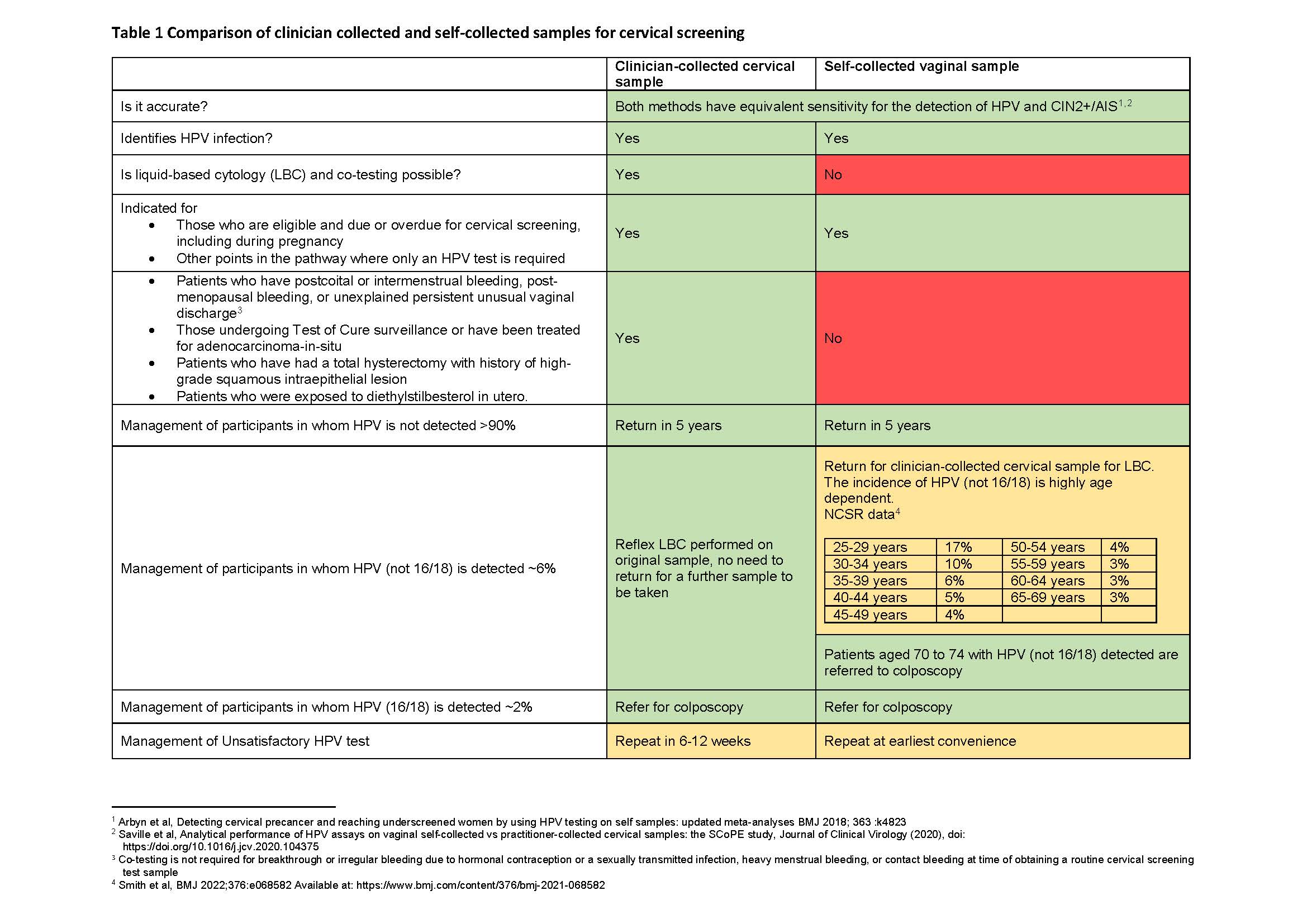

The clinical pathways within the NCSP are based on classification of CST results into low, intermediate or higher risk categories. In the vast majority (> 90%) of patients, HPV will not be detected and they can be advised to have a repeat screen in 5 years due to the test’s high negative predictive value.14 Patients in whom oncogenic HPV (not 16/18) is detected are generally advised to return as soon as is practical for a clinician-collected cytology triage test in order to determine their risk category and next steps along the pathway (Table 1). This is expected in around 6% overall of patients undertaking routine screening with highest rates in 25- to 29-year-old women (up to 17%) and lowest in those aged 50 and older (approximately 3%).15 Patients in whom HPV (16/18) is detected, expected in around 2% of routine screeners, are referred directly to colposcopy. In the updated Guidelines, cytology is recommended at the time of colposcopy.

Table 1. Comparison of clinician collected and self-collected samples for cervical screening

Unsatisfactory HPV results are very rare (around 0.2% for clinician-collected tests and 2% for self-collected tests) and all approved assays in Australia have a cellularity control which negates concerns that an empty or inadequate sample could lead to a negative HPV test result. However, while the presence of blood in the sample is generally not of concern, there is a chance that inhibition of the PCR can sometimes occur in the presence of a large amount of blood. Where possible patients can be advised to take their self-collected screening sample between menstrual periods, but screening should not be deferred if the patient is unlikely to return, and all approved assays in Australia have a control to detect assay inhibition.

Additionally, the updated Guidelines support clinicians in providing assistance to patients if they have difficulty in taking their vaginal sample, or for the clinician to collect the vaginal sample using a self-collection swab without a speculum if this is the patient’s preference. This is still classified as self-collection on pathology request form and may be useful for, for instance, patients with lack of mobility or a movement disorder.

Self-collection at any time an HPV-only test is recommended

Self-collection of a vaginal sample can also be offered as an alternative to a clinician-collected cervical sample at any time in the pathway where an HPV-only test is recommended (see Box 1). Where HPV is not detected, patients can be discharged to routine screening in 5-years, and where any HPV is detected then the patient is either advised to return for a follow-up clinician-collected cervical sample for cytology triage or referred directly to colposcopy, depending on the circumstances.

- HPV follow-up tests after an intermediate risk screening result at 12 and 24 months

- HPV test between 20 and 24 years and 9 months of age (a single HPV test could be considered on an individual basis for patients who have had sexual contact prior to age 14 and prior to HPV vaccination, but is not required)

- HPV test following either a normal or Type 3 TZ colposcopy and cytology result of negative, pLSIL or LSIL

- HPV test following total hysterectomy with no evidence of cervical pathology but an unknown screening history

Provision of additional support for patients choosing self-collection

The Guidelines recognise that unscreened and under-screened patients who access self-collection and in whom HPV is detected may require additional and individualised support to progress along the clinical pathway and to access follow-up services.

This can include reassurance and explanation with longer appointments and additional follow-up contact. At least initially, underscreened and unscreened patients who choose self-collection may have a higher risk of requiring referral to a coloposcopy service and continuity of sensitive care is essential.

Conclusion

Self-collection offers additional choice and control for participants in the NCSP and is a potential game changer in overcoming inequities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality. O&Gs and midwives are well placed to offer self-collection to patients who are under or never screened, including antenatal patients for whom this may be the first opportunity to be offered screening. Offering self-collection can help ensure the WHO cervical cancer elimination targets can be reached equitably across Australia.

References

- https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/landmark-changes-improving-access-to-life-saving-cervical-screenings

- https://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-elimination-initiative

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(18)30183-X/fulltext

- National Cervical Screening Program monitoring report 2021, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer-screening/national-cervical-screening-program-monitoring-rep/formats

- https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/2a26ae22-2f84-4d75-a656-23c329e476bb/aihw-can-141.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- https://www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/cervical-cancer-screening/management-of-oncogenic-hpv-test-results/self-collected-vaginal-samples

- Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. PubMed (nih.gov). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24433684/

- Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. The BMJ. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/363/bmj.k4823

- HPV swab self-collection and cervical cancer in women who have sex with women. The Medical Journal of Australia. Available from: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/213/5/hpv-swab-self-collection-and-cervical-cancer-women-who-have-sex-women

- Self-collection cervical screening in the renewed National Cervical Screening Program: a qualitative study. The Medical Journal of Australia. Available from: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/215/8/self-collection-cervical-screening-renewed-national-cervical-screening-program

- https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/national-cervical-screening-program?language=und

- NCSR, Healthcare Provider Portal User Guide. Available from: https://ncsr.gov.au/about-us/how-to-interact-with-the-NCSR/for-healthcare-providers/healthcare-provider-portal/healthcare-provider-portal-user-guide.html

- https://www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/cervical-cancer-screening/management-of-oncogenic-hpv-test-results/self-collected-vaginal-samples

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(13)62218-7/fulltext

- National experience in the first two years of primary human papillomavirus (HPV) cervical screening in an HPV vaccinated population in Australia: observational study. The BMJ. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/376/bmj-2021-068582

Leave a Reply