This is an abridged version of the Arthur Wilson Memorial Oration delivered at the RANZCOG Annual Scientific Meeting, held on the Gold Coast in October 2022.

Thank you to the College for the invitation to give the Arthur Wilson Oration for 2022. I was somewhat surprised to be invited to do this as I had already given the Arthur Wilson Oration in 2012. I wondered, did I not get it right the first time, they’re making me do it again! However the president has assured me that is not the case.

Dr Arthur Wilson was a prominent obstetrician, a great teacher, and a founder of what ultimately has become RANZCOG. He trained in Melbourne and practiced there from the end of the First World War, in which he served, until he died in 1947 (the year of my birth, so I never met him) and at a time when the practice, and the practitioners, of obstetrics and gynaecology were very different from today’s, as you see in the photo below. Here’s the young Dr Wilson at Royal Melbourne Hospital, on the left there, around 1920, so a century ago:

In my 2012 talk, I looked at the changes that had occurred between Dr Wilson’s time and the first decade of the 21st century, in terms of the gender of obstetricians and gynaecologists, the nature of practice, and the involvement of women in the governance of our specialty and of our College. I also took a look at what the College was like when I joined it as a Fellow in 1981, and I will just share a little of this with you now. Here is the first Council of the Australian College, RACOG, as it was in 1981:

It could truthfully be described as an old boys club – zero gender or ethnic diversity. There was definitely a culture of patriarchy, and indeed casual misogyny, I have to say, in the practice of obstetrics and gynaecology at that time, epitomised in this book cover from 1973, and these china models of mid 20th century obstetricians:

In 1981 I became one of the less than 5% of Fellows who were women, across Australia. The first woman Council member, Dr Ann Hosking, was elected from the ACT in 1984 and she was followed in 1992 by Dr Heather Munro AO, also from the ACT, and myself from NSW. As a group of just a few women Fellows in those early years, we were very active in lobbying for more women to be accepted into training, and I have to say that there was support from quite a number of male Fellows. There were also huge changes occurring in the world outside the College, which influenced what happened within it. From the mid- 1960s through to 1980 we had the second wave of feminism, women increasingly completing higher education and working outside the home, achieving equal pay, building careers, choosing their own lives. We had the availability of the Pill and other reliable contraception. By the beginning of the 21st century, that is after two decades of the College, 50% of the intake into Fellowship training was female, and 21% of Fellows were women, actively pursuing their careers.

These trends continued and by 2012, around 50% of active Fellows were women and 80% of incoming trainees identified as female (and I do note that a number of College members do not identify as either men or women).

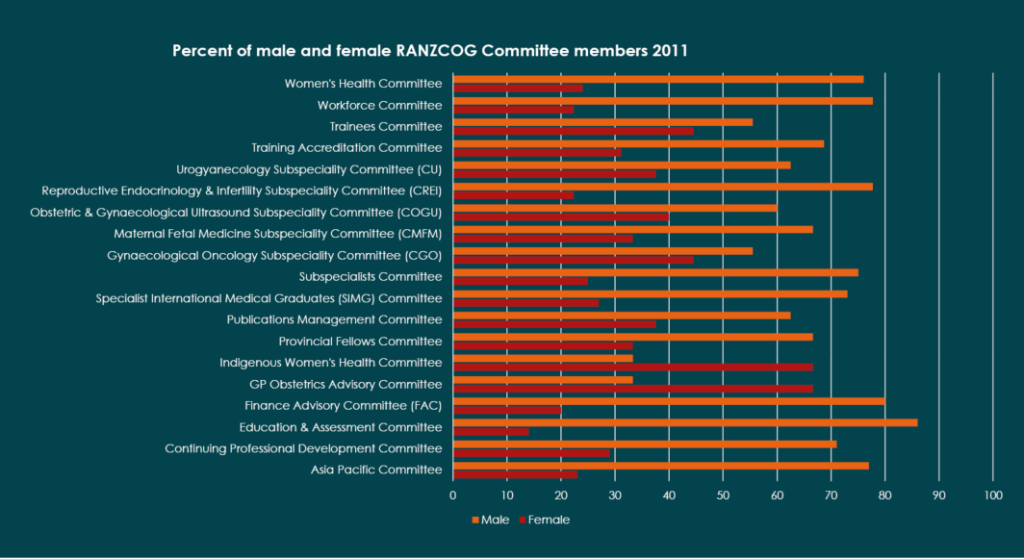

From the beginning of the 21st century onwards, more women were also putting their hands up for membership of College committees both in their home states and regions, and for Council. It was a gradual process – even in 2011, all state committees except Victoria were significantly male-dominated, as were the various Council committees, as you can see in Figure 1 – red represents women members and orange male.

Figure 1 – Percent of male and female RANZCOG committee members 2011

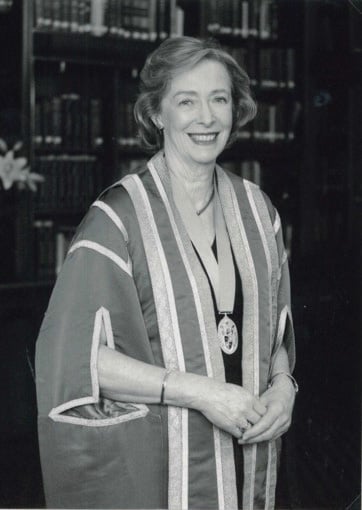

The 2012 Council were 25% female; the 2012 Executive included Dr Louise Farrell as the only petunia in the proverbial onion patch. Dr Heather Munro AO was the first and only woman president of RACOG, elected in 1994. The second woman president, the late A/Prof Chris Tippett, was elected in 2006 as president of RANZCOG following the merger of RACOG with the New Zealand College. There has been no woman president since; of the nineteen presidents elected since the Australian College was established in 1978, only two have been women. In 2012 there was still a glass ceiling that was intact.

Dr Heather Munro AO

A/Prof Chris Tippett

In 2018 there was a definite decision to confront the question of the still decreased equity and diversity within the governance of the College. In November that year the Board established the Gender Equity and Diversity Working Group (GEDWG), of which I am a member, with Dr Gill Gibson as Chair and Dr Kirsten Connan as deputy chair. The Group’s first report stated that: ‘RANZCOG recognises that being an organisation composed of members with differing skills, experience, perspectives, age, genders and cultures leads to improved leadership, stronger decision-making and better outcomes for patients.’ However, it also noted that RANZCOG had the highest percentage of female members in comparison to other Australian and New Zealand medical colleges, yet one of the lowest percentages of women in top-level leadership.

The GEDWG’s first priority was to create and implement RANZCOG’s Gender Equity and Diversity Action Plan. The first phase of the plan focused on improving gender equity within RANZCOG leadership and across the College, using prescribed targets. I’m happy to report that the targets have been met and that there has been a great deal of progress over the past four years in the gender composition of many parts of the College. In 2022, close to 60% of Fellows, 85% of trainees and 65% of Diplomates are female. In a majority of College committees there are majorities of women, reflecting the composition of the Fellowship. So the glass ceiling has been cracked, but not yet broken. We still need to see more women presidents – a succession of them over the next few years; we should not be accepting tokenism any more in this respect. We should see that the Board continues with a gender composition that reflects that of the membership as a whole.

- 238 applicants – 189 female (79.6%), 48 male (20.2%), one non-binary

- Offers for training posts: 97 female ( 82.2%), 21 male (17.6%), one non-binary

The Group’s second aim has been toward ethnic diversity. Australia is now an extremely ethnically diverse society and this is reflected right now in you, my audience today. However, the percentages of First Nations trainees and Fellows in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand are less than the percentages of First Nations people in both Australia and Aotearoa, which are 3.3% and 16.5% respectively; this needs more positive action on the part of the College and is currently a consideration for the working group.

- 134 Members identify as Indigenous

- 32 Fellows and 1 Retired Fellow identify as Indigenous:

- 7 Aboriginal Australian

- 1 Torres Strait Islander

- 11 Pacific Islander

- 14 Māori

(Identifying ethnicity/ancestry is optional)

More also needs to be done in regard to minority ethnic groups and cultures, overseas trained specialist groups, and the LGBTQIA+ community. The aim of the working group is to gain representation that reflects current membership, within leadership and in other College roles, and to address the particular needs of minority groups.

At the same time, the decline in the number of male applicants for training posts and the intake of males into Fellowship training has been a concern of the working group. I have chaired a sub-committee that has studied the reasons for the decrease, with a view to making recommendations to the RANZCOG Board, as we do not wish to see one group of young medical practitioners being completely excluded from training and practising O&G.

You can see here that male junior doctors applying for Fellowship training posts are not disadvantaged in comparison to female – the same percentages of applicants are successful in both groups. But the actual numbers of male applicants versus female have now been much smaller for nearly ten years.

My research group found that it is the experience of male medical students that most determines whether they might consider O&G as a career choice. We conducted quantitative and qualitative studies with medical students, and with junior doctors, and found that both groups felt that their experiences as students, particularly in birth suite, often led men to decide that they would not be successful in getting into training or be welcomed there. This is unfortunate, the career path should be open to all regardless of gender, and this is something the College’s group is now working on. I would not like to see the College become an almost entirely female organization, unrepresentative of the general population. I remember when it was an almost entirely male organisation, and it was an uncomfortable place for women. I believe we need to consciously ensure that male applicants for training, both as Fellows and as Diplomates, are welcome, and this includes looking carefully at how to prevent bias, whether conscious or unconscious, in the selection process for training. A decision has been made to introduce quotas including 40% of males for Council and the Board; should we also be looking at a similar quota for trainee entry?

When Arthur Wilson did his specialist training it took about a year and there were no exams. When I trained in the 1970s there were six years of medical school and three years of MRCOG training. Now it takes up to eight years to graduate as a doctor, followed by internship. Admission to the training program brings another six years of rotations through a number of different urban and rural hospitals, the many demands of the core training assessment and major exams. Subspecialty training takes even longer.

The years when a woman or pregnancy-capable trainee is undertaking all this are almost always their twenties and early thirties, exactly the time in which, as obstetricians, we would advise a person who wishes to have children that they should try to do so. This dichotomy has been recognised by the College. Over the past thirty years there has been very vigorous discussion within the College around the topic – but we certainly gained job-sharing, very early, in 1985, and it was introduced through the efforts of the woman I’ve already mentioned, Ann Hosking, the first woman member of the College Council. Many trainees now have been able to take maternity leave and return into recognised posts in the training scheme, and some have taken paternity leave. Once training is completed there is also a growing tendency in private obstetrics to group practice, by both women and men, and as someone who spent seventeen years in solo private obstetric practice in Sydney, I think this is an essential and very welcome development, and one well-received by the majority of women, and indeed men. There are also now very many more staff specialist jobs which may be part- or full-time, in which women can practise our specialty while also having a family. On the other hand, it’s also essential that trainees of all genders get adequate clinical experience during their training years and continue to maintain their skills as they practise, whether that’s full or part-time; it’s essential to be completely professional.

Over the 41 years I have been a Fellow I have seen enormous growth and evolution of the College. From time to time I have considered the question of whether we actually need a College, sometimes in discussion with colleagues, sometimes on my own. I always come up with the answer that yes, we do – despite occasionally being annoyed or depressed or infuriated by some decision or action of some part of the College. The educational, assessment, accreditation, research and advocacy roles of our College are all essential to our individual abilities to continue as specialist obstetricians and gynaecologists. At the heart of the College structure is the apprenticeship model of learning that is essential for professions that depend on the skills of both the hands and the brain. We can only learn from our elders who are already experts in the areas we aspire to. I do not think the unique role of medical colleges could be bettered by a university system, and certainly not by a governmental one. But the structure of the College requires the voluntary participation of active Fellows and trainees and Diplomates, because it’s the practitioners who have the know-how about what obstetrics and gynaecology actually is.

There is a tendency for trainees and new Fellows to be a bit in awe of ‘the College’ and it’s not unknown for established Fellows to be critical or dismissive. ‘The College’ sometimes is seen as an anonymous and uncaring building somewhere down in Melbourne. In fact, ‘the College’ is you, its members; you control it and the more involved you become the more it will reflect who you are. So I strongly recommend to trainees and recent Fellows – put up your hand and join in College activities. The more who do so, the stronger our College will be.

Arthur Wilson, were he here today, would be amazed by what the College has become, in terms of its membership, its many functions, and its contribution to reproductive healthcare in Australia and New Zealand. But I also think he would be impressed.

Thank you.

Leave a Reply