Cancer in pregnancy

Cancer in pregnancy is extremely rare, affecting approximately 1 in 2000 pregnancies. A rise in incidence is expected and is becoming evident in population-based studies. Delayed child-bearing and non-invasive prenatal testing (which may detect asymptomatic cancer) are the most likely contributory factors.1

Involvement of a multidisciplinary team is crucial to the sound and evidence-based management of any malignancy, and this is particularly applicable to cancers in pregnancy which remain uncommon. Given dilute experience in gestational cancer management amongst both treating specialists and centers, collaboration is key and should involve discussion between senior oncologists, maternal-fetal medicine specialists and perinatologists. Key resources are available through the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy2 including a 2019 publication which provides international consensus-based guidelines.3

In an effort to address the paucity of Australian data on cancer in pregnancy, the Cancer Council of New South Wales are co-ordinating a state-wide investigation into gestational cancers.4 The results of this project will inform the creation of evidence-based and patient-centred resources, leading to improved quality of care and better support for women with cancer in pregnancy in Australia.

The overarching principle of gestational cancer management is to manage the malignancy on its merits, and then determine what allowances can be made for the pregnancy and the fetus. When making decisions about investigation and management, the aims are:

- To account for both maternal and fetal concerns

- To facilitate standard maternal treatment if possible

- To prevent iatrogenic prematurity

Cervical cancer in pregnancy

Approximately 5% of pregnant women will have abnormal cervical cytology and routine antenatal care should include a cervical screening test if due. Colposcopic examination of the pregnant cervix should be undertaken by an experienced colposcopist. Indications for urgent referral to a gynaecologic oncologist include LBC prediction of invasive disease, colposcopic impression of invasive carcinoma, and histologically confirmed invasive carcinoma. The National Cervical Screening Guidelines are a great resource, providing a clear and succinct strategy for the management of HSIL on cytology in pregnancy.5

Colposcopy in pregnancy is undertaken with a view to excluding invasive disease. High-grade lesions diagnosed during pregnancy can be safely deferred for treatment until after delivery because progression to invasive disease during the pregnancy is rare. Of those cases that do progress, most are microinvasive and amenable to curative treatment. Biopsy is safe during pregnancy but is not usually necessary unless invasive disease is suspected.

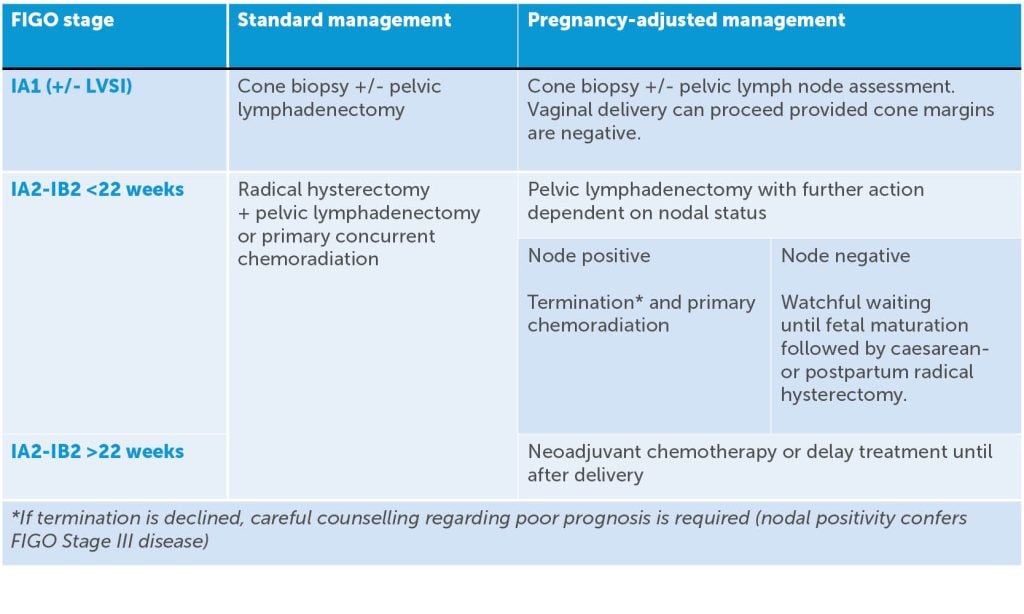

Once a tissue diagnosis of invasive cervical cancer in pregnancy has been made, the next step is to determine disease extent. Radiologic staging investigations in the non-pregnant patient include MRI pelvis and FDG–PET.6 In the pregnant woman, most clinicians would make allowances for the fetus by instead using CXR with abdominal shielding and MRI. As in the non-pregnant patient, a variety of treatment options are available but are dependent on stage of disease and maternal desire to continue the pregnancy. When considering these options, it is useful to first consider standard management, then consider how such management might be adjusted to account for the pregnancy. Table 1 provides a guide for comparing standard management versus pregnancy-adjusted options for early-stage disease.

Table 1. Standard management for cervical cancer versus pregnancy-adjusted options for early-stage disease.

Ovarian cancer in pregnancy

As in the non-pregnant state, most ovarian malignancies are diagnosed after surgical excision with majority presenting as asymptomatic adnexal masses, commonly detected on ultrasound examination. Approximately 2.4% of pregnancies are complicated by an adnexal mass, and 1-6% of these masses are malignant.7 8 9 10 Ovarian cancer ranks behind breast, haematologic, thyroid and gastrointestinal tract11 as the most common primary sites for cancers diagnosed during pregnancy but remains the second most common gynaecological malignancy after cervical cancer. Epithelial subtypes make up approximately 50% of cases, (half of which are borderline tumours), germ cell tumour representing another third and rarer tumour types and metastases making up the rest of presentations.

When symptomatic, complaints are similar to those regularly reported during pregnancy (eg. abdominal swelling/discomfort, back/pelvic pain, constipation and urinary frequency), making diagnosis even more challenging. Other times when an adnexal mass has been diagnosed in pregnancy have been after adnexal torsion or incidentally at caesarean delivery.

Ovarian tumour markers (eg. AFP, CA125, hCG, LDH, inhibin) are not as useful in pregnancy as levels may be influenced by gestational age, fetal abnormalities and maternal comorbidities. Consequently, the use of ultrasound and MRI to characterise adnexal masses are more heavily relied upon when suspicions for ovarian cancer are raised. Features such as solid components, papillary projections, septations and vascular elements or evidence of loco-regional disease should prompt referral for gynae oncology opinion and management. CT should be avoided as exposure has been linked with miscarriage, congenital abnormalities, IUGR, neurological effects12 13 14 15 16 and childhood cancer and leukaemia.17 18

Surgical intervention is generally indicated where suspicion for malignancy is significant or when lesion size may confer an increased risk for rupture, torsion or labour obstruction. Surgery is preferably performed in early second trimester by a multidisciplinary team (gynae oncologist, high risk obstetrician, neonatology, anaesthetics, midwifery and allied health) with cases diagnosed later often able to be managed expectantly. A unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy +/- staging should be performed through an incision which will maximise exposure, avoid tumour disruption and minimise manipulation of the pregnant uterus. Peritoneal washings and thorough inspection of the abdominopelvic cavity should be performed and biopsies from suspicious areas taken for pathological assessment. Frozen section may be utilised if this would change the patient’s wishes for intra-operative management. The role of primary cytoreduction in the setting of advanced stage disease would not generally be considered if other treatment options (eg. neoadjuvant chemotherapy) are available.

Ultimately, pathological confirmation is key to guiding the ongoing management of both patient and pregnancy and should be discussed at a multidisciplinary level with recommendations for treatment highly dependent on gestational age, extent of disease and patient wishes. Further surgery is generally reserved until after delivery and systemic chemotherapy can and has been used safely during pregnancy, but needs to be balanced against chemotherapeutic side effects and possible risks (eg. congenital malformation, premature labour, IUGR, neonatal marrow suppression).

Non-gynaecologic malignancies in pregnancy

Breast is the most common cancer in pregnancy with an incidence of 2.3 to 40 cases per 100,000 women.19 Over 90% of patients will present with a palpable mass.20 The histology of tumours appears to age-matched women who are not pregnant but the stage of disease at diagnosis is more advanced which incurs a worse prognosis. This is likely due to a delay in diagnosis.21 Diagnosis is made on USS and core biopsy. Surgery and chemotherapy are the main treatment of choice. Radiotherapy, endocrine therapy and target therapy are generally contraindicated.

Colorectal cancer is the seventh most common type of cancer diagnosed in pregnancy, with an estimated incidence of 7–8 per 100,000 pregnancies.22 Diagnosis can be challenging as the signs and symptoms are masked by pregnancy.23Approximately 60% present at an advanced stage (at least stage III) and 86% are generally in the lower rectum.24 Diagnostic investigations like endoscopies can be difficult but may be necessary depending on the clinical suspicion. Management principles are the same as other cancers in pregnancy.

Lymphomas, most commonly Hodgkins lymphoma, are the fourth most common malignancy in pregnancy occurring in approximately 1 in 6000 pregnancies.25 26 Diagnosis is often delayed due to an overlap of features characterising both the malignancy and pregnancy (weakness, sweating, shortness of breath, pain).27

Treatment options are generally dependent upon histological diagnosis, stage at presentation, gestation, and maternal wishes regarding the pregnancy. Given the rarity of haematological malignancies in pregnancy, multidisciplinary involvement is important. Given the increased risks of chemotherapy to the developing fetus in the first trimester, if possible, chemotherapy should be delayed until the second trimester unless this compromises maternal outcome.28 If treatment cannot be delayed beyond the first trimester, then pregnancy termination may be required. Broadly, acute leukemias should be managed without delay as any delay may seriously affect maternal prognosis. Conversely, lymphoma treatment may be delayed without maternal risk.29

Rare cancers in pregnancy

In Australia, despite lung cancer being the fourth commonest cancer diagnosed in women and the leading cause of cancer related mortality,30 its incidence in pregnancy is rare. Adenocarcinomas are the most common histology, accounting for approximately 80% of cases.31 >97% of women are diagnosed with locally advanced or metastatic disease; possibly due to symptoms being attributed to other causes or a reluctance to investigate in pregnancy.32

Treatment options are largely drawn from expert consensus opinion, case reports and standard treatment options in non-pregnant women. Given this, and that maternal outcome in lung cancer is generally very poor with many women succumbing to their disease within the first year after delivery,33 multidisciplinary discussion is vital. Obstetricians and neonatologists should be involved in the decision-making process.

The management of rare gynaecological tumours in pregnancy including endometrial, vulval and vaginal cancer is derived largely from case reports, expert opinion, and extrapolation from management outside of pregnancy.

Endometrial cancer diagnosed shortly after pregnancy (whether first trimester loss or term pregnancy34) is generally associated with a favourable prognosis. Most are reported to be low grade and can be managed as standard. Uncommonly, endometrial cancer may be diagnosed on uterine sampling on a woman who is subsequently found to be pregnant. In these cases, standard of care does not allow for continuation of the pregnancy.35

There is an increasing incidence of vulval cancer in young women, which may result in diagnoses during pregnancy.36 Early vulval cancer can be managed similarly to outside of pregnancy, including radical wide local excision and sentinel node biopsy, although the management needs to be tailored to the pathological features of the malignancy and the gestation of pregnancy.37 The sentinel node biopsy can be performed with technetium-99 and a gamma detection probe with omission of lymphoscintigraphy.38 Caesarean delivery is advised. In the very rare occurrence of an advanced vulval cancer, care should be tailored to the gestation at diagnosis, and may include the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in pregnancy prior to delivery and definitive management.

Vaginal cancer is exceedingly rare in pregnancy with limited case reports.39 The approach to management is multidisciplinary team consensus based, and depends on stage, with extrapolation on treatment options from the more commonly seen cervical cancer in pregnancy.

Complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy with co-existing fetus is uncommon and reported to occur between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 100,000 pregnancies. Management should be tailored to take into account the features of the live fetus (karyotype and anatomy) as well as the potential for pregnancy complications in the woman, including pre-eclampsia.40

Our feature articles represent the views of our authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), who publish O&G Magazine. While we make every effort to ensure that the information we share is accurate, we welcome any comments, suggestions or correction of errors in our comments section below, or by emailing the editor at [email protected].

References

- Wolters V, et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:314-22.

- www.cancerinpregnancy.org

- Amant F, et al. Annals of Oncology. 2019;0:1-12.

- www.cancercouncil.com.au/research-pt/cancer-and-outcomes-in-pregnancy-a-nsw-evaluation-cope

- www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/cervical-cancer-screening

- Bhatla N, et al. Int J Gynaecol Cancer. 2018;143 Suppl 2:22-36.

- Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, et al. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1098.

- Smith LH, Dalrymple JL, Leiserowitz GS, et al. Obstetrical deliveries associated with maternal malignancy in California, 1992 through 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1504.

- Webb KE, Sakhel K, Chauhan SP, Abuhamad AZ. Adnexal mass during pregnancy: a review. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32:1010.

- Aggarwal P, Kehoe S. Ovarian tumours in pregnancy: a literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:119.

- Shim MH, Mok CW, Chang KH, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of cancer diagnosed during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016; 59:1.

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion. Number 299, September 2004 (replaces No. 158, September 1995). Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:647.

- Harvey EB, Boice JD Jr, Honeyman M, Flannery JT. Prenatal x-ray exposure and childhood cancer in twins. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:541.

- International Commission on Radiological Protection. Pregnancy and medical radiation, Publication 84. Annals of the ICRP 30;1; 2000.

- Sharp C, Shrimpton JA, Bury RF. Diagnostic Medical Exposures: Advice on Exposure to Ionising Radiation during Pregnancy. National Radiological Protection Board, College of Radiographers, Royal College of Radiologists; 1998.

- International Commission on Radiological Protection. Biological effects after prenatal irradiation (embryo and fetus), Publication 90. Annals of the ICRP 33;1-2; 2003.

- Doll R, Wakeford R. Risk of childhood cancer from fetal irradiation. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:130-9.

- Wakeford R, Little MP. Risk coefficients for childhood cancer after intrauterine irradiation: a review. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:293-309.

- Andersson TML, Johansson ALV, Chung-Cheng H, et al. Increasing incidence of pregnancy-associated breast cancer in Sweden. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:568-72.

- Middleton LP, Amin M, Gwyn K, et al. Breast carcinoma in pregnant women: assessment of clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features. Cancer. 2003;98:1055-60.

- Zemlickis D, Lishner M, Degendorfer P, et al. Maternal and fetal outcome after breast cancer in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:781-7.

- Woods JB, Martin JN Jr, Ingram FH, et al. Pregnancy complicated by carcinoma of the colon above the rectum. Am J Perinatol. 1992;9(2):102-10.

- Yaghoobi M, Koren G, Nulman I. Challenges to diagnosing colorectal cancer during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(9):881–5.

- Dogan NU, Tastekin D, Kerimoglu OS, et al. Rectal cancer in pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2013;44(3):354-6.

- El-Hemaidi I, Robinson SE. Management of haematological malignancy in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:149-60.

- Di Ciaccio PR, Mills G, Tang C, Hamad N. Managing haematological malignancies in pregnant women. Lancet Haematology. 2021;8:e623-e4.

- www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/cervical-cancer-screening

- El-Hemaidi I, Robinson SE. Management of haematological malignancy in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:149-60.

- Mahmoud HK, Samra MA, Fathy GM. Hematologic malignancies during pregnancy: A review. J Adv Res. 2016;7:589-96.

- John T, Cooper WA, Wright G, et al. Lung Cancer in Australia. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:1809-14.

- Soares A, Dos Santos J, Silva A, et al. Treatment of lung cancer during pregnancy. Pulmonology. 2020;26:314-7.

- Soares A, Dos Santos J, Silva A, et al. Treatment of lung cancer during pregnancy. Pulmonology. 2020;26:314-7.

- Soares A, Dos Santos J, Silva A, et al. Treatment of lung cancer during pregnancy. Pulmonology. 2020;26:314-7.

- Shiomi M, Matsuzaki S, Kobayashi E, et al. Endometrial carcinoma in a gravid uterus: a case report and literature review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2019;19(1):1-9.

- Korenaga TR, Tewari KS. Gynecologic cancer in pregnancy. Gynecologic oncology. 2020;157(3):799-809.

- Soo-Hoo S, Luesley D. Vulval and vaginal cancer in pregnancy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2016;33:73-8.

- Gaunt E, Pounds R, Yap J. Vulval cancer in pregnancy: Two case reports. Case Reports in Women’s Health. 2022 ;33:e00374.

- Korenaga TR, Tewari KS. Gynecologic cancer in pregnancy. Gynecologic oncology. 2020;157(3):799-809.

- Korenaga TR, Tewari KS. Gynecologic cancer in pregnancy. Gynecologic oncology. 2020;157(3):799-809.

- Korenaga TR, Tewari KS. Gynecologic cancer in pregnancy. Gynecologic oncology. 2020;157(3):799-809.

Leave a Reply