What is health literacy and why is it important?

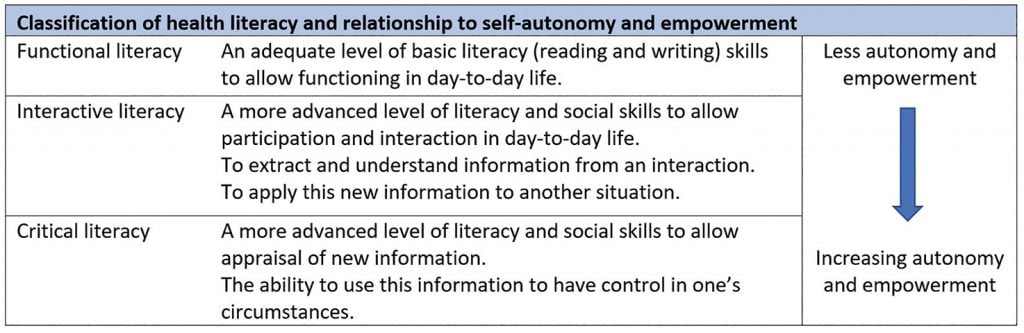

Health literacy can be defined as ‘the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions’.1 It extends further than the ability of the individual to read patient information, access health information electronically or to follow instructions that they are given. It also includes the capacity of the individual to make decisions in their personal context to promote their health needs and the needs of their society, increasing their autonomy and empowerment (Figure 1).2 The relationships between reading ability (literacy) and health literacy, health literacy and electronic health literacy are complicated and not reciprocal.3

Figure 1. Classification of Health Literacy (adapted from Nutbeam et al)[note]Graham S, Brookey J. Do patients understand? The Permanente Journal. 2008;12(3):67-9.

Levels of health literacy impact on the individual and their interactions with the healthcare system.6 People with lower health literacy are more likely to have worse health outcomes overall with higher rates of chronic disease, hospitalisation and mortality.7 Lower levels of health literacy are associated with lower education levels, lower socioeconomic status, minority gender and sexual identity groups, increased age, and those from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. These are commonly referred to under the umbrella of ‘the social determinants of health’ and may contribute to the health inequality that is experienced by clients with these characteristics.8 9 In contrast, higher levels of health literacy are associated with increased patient involvement in shared decision making, and better health outcomes. The national survey demonstrated that higher levels of health literacy correlated with younger age, decreasing remoteness of residence, and increased education, participation in ongoing learning, being employed and increased technicality of employment.10

It is important to note that there is limited data on health literacy levels in Indigenous Australians and people from CALD backgrounds, with available data suggesting lower health literacy levels in these groups.11 12 Both the Indigenous and CALD communities want to be involved in their healthcare and decision-making processes, but often lack the understanding to effectively do so.13 Patterns for understanding health literacy levels in the Indigenous and CALD populations are complex and involve consideration of age, gender, socioeconomic status and health status.14

The emphasis on patient-centred care and shared decision making underpins our modern approach to healthcare. The importance of understanding health literacy in this context is highlighted in Table 1, illustrating that low health literacy decreases patient autonomy and empowerment, limiting the capacity of delivery of person-centred care.15

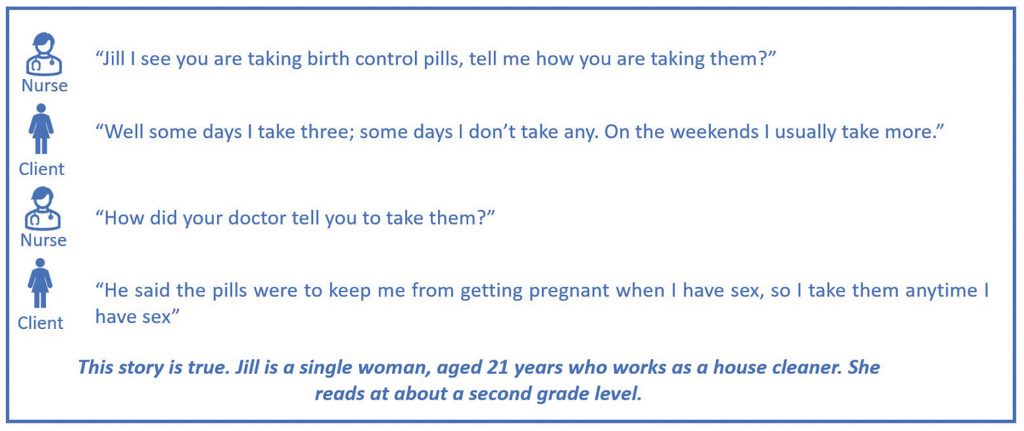

Case study image. Adapted from Graham and Brookey, Do patients understand? The Permanente Journal. 2008;12(3):67-9

How is health literacy different in sexual and reproductive health?

Health literacy in the domain of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) ‘goes beyond knowledge and behaviour and is the self-perceived ability of an individual to access the needed information, understand the information, appraise and apply the information into informed decision making for a good way to contribute to sexual and reproductive health.’16 The World Health Organization discusses SRH literacy in the context of fertility planning and contraceptive access, sexually transmitted infections, relationships and domestic violence and gender inequality.17 Autonomy in these areas allows an individual, especially a woman, to be able to improve their health and place in society and correlate with multiple Sustainable Development Goals.18

Sexual and reproductive healthcare is thus an area where the social determinants of health are highlighted due to the status and rights of women internationally. Internationally, women are more likely to be poor, uneducated, victimised by culture, religion or government policy, subject to food and financial insecurity, lack autonomy and be marginalised in societies – thus have less social capital to gain their human right to basic healthcare.19 These situations create and perpetuate poor health literacy, yet in their life course all women will have significant health needs that require greater than functional health literacy to access and navigate healthcare providers and services.

Research on the relationship between health literacy and women’s reproductive health has shown that low health literacy has a negative effect on women’s health knowledge and engagement in preventative behaviours and impacts their ability to navigate the health system and care for their children.20 Using fertility planning as an example, low health literacy is associated with less understanding of menstrual cycle physiology, mechanisms of pregnancy, purpose and use of contraception, and a potential association with unplanned pregnancy.21 Women with low health literacy are also more likely to not understand instructions regarding contraceptive use22 and how to modify use and sexual behaviour when it is incorrectly used.23

What are the impacts of low health literacy and what can we do?

The consequences of low health literacy are far reaching and impact individuals and their families, the health system and may have medico-legal implications for the healthcare provider regarding their duty of care and consent of clients. If the healthcare worker is unable to accurately identify the client’s level of health literacy, and thus their capacity to be involved in the consultation process, then they will not respond appropriately to their client’s need. The result of this is that they will not offer an appropriate level of care, engage in the delivery of patient-centred care, or be able improve the health status through effectively offering preventative measures.24

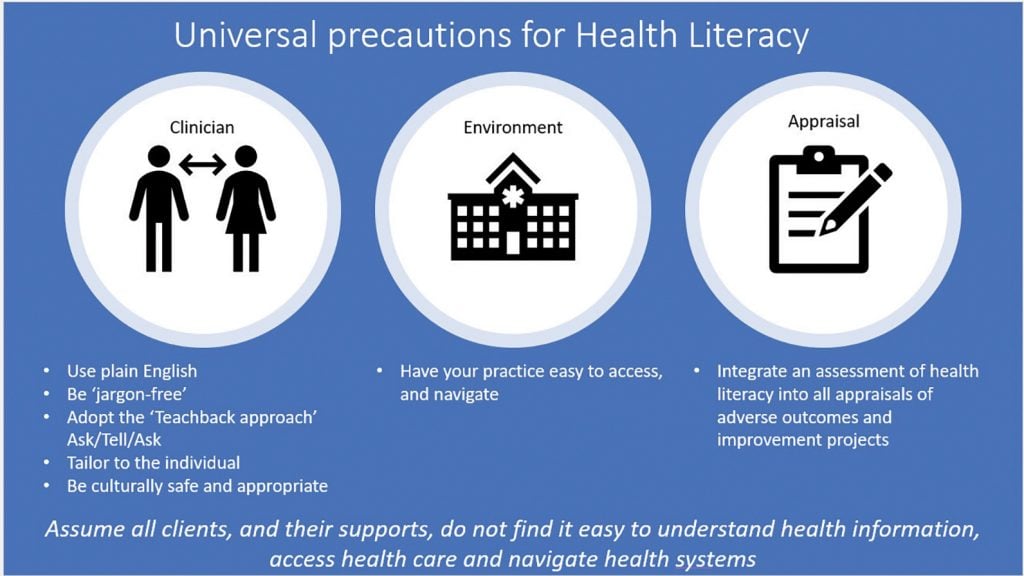

Health professionals usually have an awareness of health literacy but often misjudge the health literacy level of the individual, as well as overestimating their communication skills.25 26 Factors such as limited consultation time also constrain the ability to cater for individuals and their needs.27 Routine measurement of the client’s health literacy is not recommended as it has not been shown to improve patient outcomes. This is in part due to inaccurate measurement and classification, and as it is not a static characteristic.28 29 30 31 Thus the concept of ‘health literacy universal precautions’ is important as it can improve care for all patients through the assumption that every patient has difficulty understanding information in a medical consultation.

The Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare recommends that universal health literacy precautions be employed in both the consultation with an individual patient, and the environment or health system that they need to access.32 Things to consider for your practice environment include factors at the individual and organisational level as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Health Literacy Universal Precautions.

Strategies for individual client consultations include the use of plain, jargon-free language and adopting methods to ensure client understanding such as the ‘teach-back method’.33 This technique involves having the client teach back to the clinician the key information and messages conveyed within a consultation. Assuming that a patient understands without checking comprehension leads to a mismatch in clinician-client communication. The teach-back method can be applied by all staff within a health service, both clinical and non-clinical, so that patients can navigate health locations, appointments, and consultations better. Using other tools in conversation, such as the Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT) recommended by the Clinical Excellence Commission, will give healthcare providers a way to ask about facets of health literacy if this has not previously been part of their practice.34

Consideration should also be given to any patient information. This includes information on medical conditions, treatment options and associated risks, and available services. Readability of patient materials is often at a higher literacy level than patient capability and evidence suggest that less text can lead to improved understanding.35 36 A balance between the need to convey relevant clinical information with a consideration to an individual’s information capacity must therefore be met. Using the strategies above, information can be delivered in a manner that empowers the patient through improved understanding of their health.

Strategies at an organisational level include ensuring health services are easy to find, access and navigate. Ultimately, the health literacy of Australia’s priority populations can only be improved by addressing the wider social determinants of health.37 This begins with strategies to improve the way priority populations access their health information. The use of mainstream and culturally specific media channels can increase the reach of health information. Additionally, available health information must be reliable, trustworthy, culturally appropriate, and easy to understand. For our Indigenous and CALD populations, this information should be led by their community and disseminated under community guidance. These simple measures will build environments where individuals can be actively involved in decisions about their own health and contribute to collective action to improve the health of their community.

Patient-centred care and shared decision making are two principles that underpin our healthcare system. Health literacy is directly correlated with a client’s autonomy and empowerment. We cannot assume that all individuals have a satisfactory health literacy to achieve this. It is our responsibility as healthcare providers to enable an environment that recognises individuals with low levels of health literacy and empower them to participate in decisions about their healthcare. Adopting the universal precautions for health literacy will increase compliance, improve outcomes and the overall healthcare of individuals, communities and the wider population.

References

- Ratzan S, Parker R. Health literacy. National Library of Medicine, Current bibliographies in Medicine Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2000.

- Nutbeam D, Muscat DM. Health Promotion Glossary 2021. Health Promotion International. 2021;36(6):1578-98.

- Monkman H, Kushniruk AW, Barnett J, et al. Are Health Literacy and eHealth Literacy the Same or Different? Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;245:178-82.

- Australian Government. Style Manual, Literacy and Access. 2021. Available from: stylemanual.gov.au/accessible-and-inclusive-content/literacy-and-access.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: Health literacy 2019. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/national-health-survey-health-literacy/latest-release.

- Peerson A, Saunders M. Health literacy revisited: what do we mean and why does it matter? Health Promot Int. 2009;24(3):285-96.

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155(2):97-107.

- Kickbusch I, Pelikan J, Apfel F, Tsouros A. Health Literacy: the Solid Facts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Marmot M, Allen JJ. Social Determinants of Health Equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(S4):S517-S9.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: Health literacy 2019. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/national-health-survey-health-literacy/latest-release.

- Beauchamp A, Buchbinder R, Dodson S, al. Distribution of health literacy strengths and weaknesses across socio-demographic groups: a cross-sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):678.

- Rheault H, Coyer F, Jones L, Bonner A. Health literacy in Indigenous people with chronic disease living in remote Australia. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):523.

- Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, Cultural and Indigenous Research Centre Australia. Consumer health information needs and preferences: perspectives of culturally and linguistically diverse and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Sydney; 2017.

- Beauchamp A, Buchbinder R, Dodson S, al. Distribution of health literacy strengths and weaknesses across socio-demographic groups: a cross-sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):678.

- Korda RJ, Banks E, Clements MS, Young AF. Is inequity undermining Australia’s ‘universal’ health care system? Socio-economic inequalities in the use of specialist medical and non-medical ambulatory health care. Australian And New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2009;33(5):458-65.

- Vongxay V, Albers F, Thongmixay S, et al. Sexual and reproductive health literacy of school adolescents in Lao PDR. PloS one. 2019;14(1):e0209675.

- World Health Organization. Sexual and reproductive health literacy and the SDGs: World Health Organization; 2021. Available from: www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/9gchp/sexual-reproductive-health-literacy/en/.

- World Health Organization. Sexual and reproductive health literacy and the SDGs: World Health Organization; 2021. Available from: www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/9gchp/sexual-reproductive-health-literacy/en/.

- Floyd A, Sakellariou D. Healthcare access for refugee women with limited literacy: layers of disadvantage. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2017;16(1):1-10.

- Shieh C, Halstead JA. Understanding the Impact of Health Literacy on Women’s Health. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2009;38(5):601-12.

- Kilfoyle KA, Vitko M, O’Conor R, Bailey SC. Health literacy and Women’s reproductive health: a systematic review. Journal of Women’s Health. 2016;25(12):1237-55.

- El-Ibiary SY, Youmans SL. Health literacy and contraception: a readability evaluation of contraceptive instructions for condoms, spermicides and emergency contraception in the USA. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2007;12(1):58-62.

- Zapata LB, Steenland MW, Brahmi D, et al. Patient understanding of oral contraceptive pill instructions related to missed pills: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87(5):674-84.

- Parikh NS, Parker RM, Nurss JR, et al. Shame and health literacy: the unspoken connection. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27(1):33-9.

- Byrne JV, Whitaker KL, Black GB. How doctors make themselves understood in primary care consultations: A mixed methods analysis of video data applying health literacy universal precautions. PloS one. 2021;16(9):e0257312.

- Voigt-Barbarowicz M, Brütt AL. The Agreement between Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Assessment of Patients’ Health Literacy-A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(7).

- Turner T, Cull WL, Bayldon B, et al. Pediatricians and health literacy: descriptive results from a national survey. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Suppl 3:S299-305.

- Voigt-Barbarowicz M, Brütt AL. The Agreement between Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Assessment of Patients’ Health Literacy-A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(7).

- Weiss BD. How to bridge the health literacy gap. Family practice management. 2014;21(1):14-8.

- Weiss BD. Health literacy and patient safety: Help patients understand. Manual for clinicians: American Medical Association Foundation; 2007.

- Batterham RW, Hawkins M, Collins PA, et al Health literacy: applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public Health. 2016;132:3-12.

- Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare. Health Literacy: a summary for clinicians 2015. Available from: www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/Health-literacy-a-summary-for-clinicians.pdf.

- Batterham RW, Hawkins M, Collins PA, et al Health literacy: applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public Health. 2016;132:3-12.

- O’Hara J, Hawkins M, Batterham R, et al Conceptualisation and development of the Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT). BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):199.

- Rooney MK, Santiago G, Perni S, et al. Readability of patient education materials from high-impact medical journals: a 20-year analysis. Journal of Patient Experience. 2021;8:2374373521998847.

- Freer Y, McIntosh N, Teunisse S, et al. More information, less understanding: a randomized study on consent issues in neonatal research. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):1301-5.

- Nutbeam D, Muscat DM. Health Promotion Glossary 2021. Health Promotion International. 2021;36(6):1578-98.

Leave a Reply