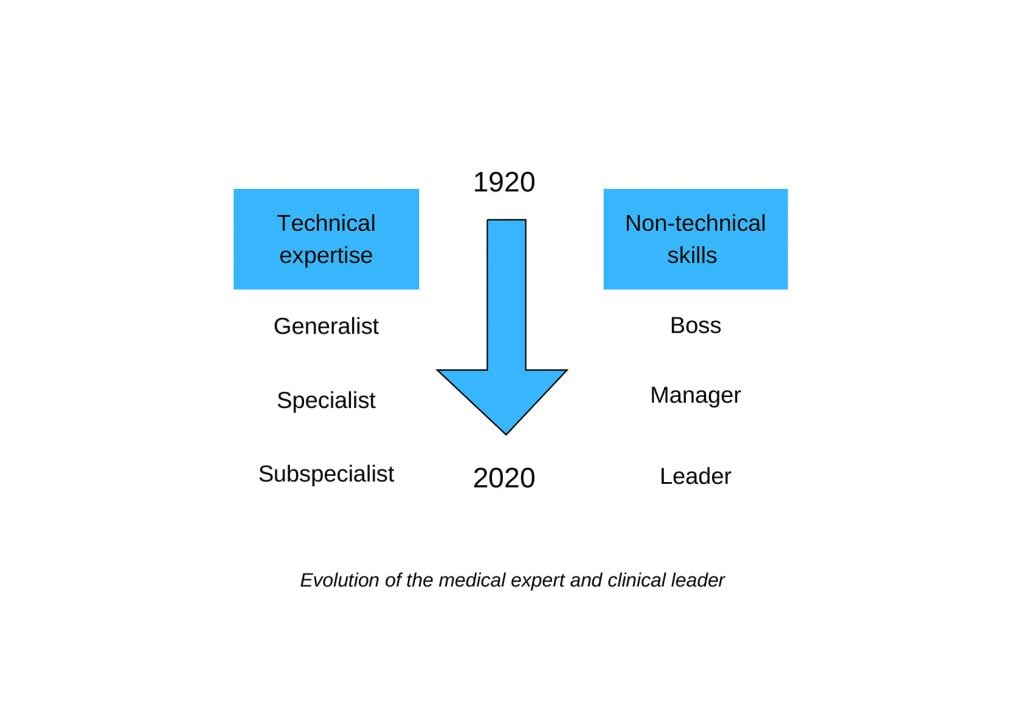

The past 100 years of medicine have seen an evolution of the practice, in both medical expertise and non-technical expectations of the doctor’s role (Figure 1). Although drivers, content, and methods have changed, learning and teaching within the craft have remained a constant requirement.

Figure 1. Evolution of the medical expert and clinical leader.

The changing role of medical practice

The foundation of medical colleges in Australia between 1920–1950 led to the dominance of teaching hospitals and the rise of subspecialties by 1975.1 Alongside these changes, senior doctors were engaged as clinical leads, medical managers and medical leaders. This terminology reflects not simply a change of title but a shift in role as the complexity of healthcare and health systems has evolved.

The preceding three centuries were dominated by a model of understanding based upon superficial, linear, hierarchical relationships. Complexity science and healthcare as a complex adaptive system inform a modern interpretation of our work, primarily driven by rapidly changing technology and information.

Where traditional systems thrived on stabilisation, control, rigidity and knowledge-as-power, complexity demands attention to connections, relationships and styles of practice and leadership outlined in Table 1. In this environment, lifelong learning has undergone a similar transformation of context, content and how we maintain skills across these broad domains of practice.2

Table 1. Leadership traits in different systems.3

| Healthcare professionals in | |

|---|---|

| Traditional systems: | Complex adaptive systems: |

| Are controlling, mechanistic | Are open, responsive, catalytic |

| Repeat the past | Offer alternatives |

| Are ‘in charge’ | Are collaborative |

| Are autonomous | Are connected |

| Are self-preserving | Are adaptable |

| Resist change, bury contradictions | Acknowledge paradoxes |

| Are disengaged, nothing changes | Are engaged, continuously emerging |

| Value position and structure | Value persons |

| Hold formal position | Are shifting as processes unfold |

| Set rules | Prune rules |

| Make decisions | Help others |

| Are knowers | Are listeners |

Healthcare regulation as a driver for lifelong learning

With an increasing demand for accountability and transparency, there is pressure by the public on legislators to safeguard high-quality care and patient safety, and to ensure that all doctors are competent. Certification of specialists and specialty practice varies worldwide, so colleges need to assess internationally qualified specialists as suitable for unsupervised practice in Australia. Once specialist qualification is achieved, there are a range of methods for recertification. The RANZCOG Continuing Professional Development (CPD) program requires 50 hours per year across the three domains of educational activities, outcome measurement and performance review. UK recertification is carried out five-yearly and includes collation of a portfolio like RANZCOG, with additional evidence of significant clinical events and feedback and review of complaints and compliments from patients and colleagues. Recertification in the UK also requires annual appraisals by employers. There has been a call for international evidence-based consensus for CPD and lifelong learning frameworks.4

Lifelong learning approaches

Lifelong learning is described as ‘the development of human potential through a continuously supportive process which stimulates and empowers individuals to acquire the knowledge, values and skills and understanding they will require throughout their lifetimes and apply them with confidence, creativity and enjoyment in all roles, circumstances and environments.’5 This somewhat wordy definition emphasises the importance of metacognitive and meta-learning skills (thinking about how we think and learn) across situations in which we work. A fundamental aptitude is self-awareness of our limitations of thinking and the ability to adopt different mental models for a changing and unpredictable environment. Cognitive neuroscience has taught us much in recent years about learning more effectively.

Undergraduate education methods are well studied; however, little is known about active engagement in lifelong learning within contexts other than those dedicated to learning. This is important because a significant component happens within the clinical space and situations not intrinsically suited for active learning.

Self-regulated learning (SRL) describes the process of goal setting, planning, monitoring, metacognition, attention, learning strategies, persistence, time management, motivation, emotional control and effort. This often occurs as part of a structured training program in postgraduate medicine, such as one for college Fellowship. There has been a shift, and recent studies indicate that trainees engage in self-regulated learning before, during and after patient encounters, use feedback on performance for self-reflection and to guide learning.6 This may suggest that efforts to make undergraduate medical education more active, learner-centred and self-regulated have also affected postgraduate development.

Social relationships, workplace-based learning, feedback and self-reflection on real issues encountered in a doctor’s life whilst practising medicine are essential for acquiring and improving competencies.7 Reflective practice aids professional development, reduces diagnostic errors8 and can help process emotions, improve mood, prevent burnout and improve patient care.9

Incremental learning is well established and known to us: we learn facts and technical skills and align habits with established norms and expert opinions. Transformative learning is how we internalise and interpret our own experiences to date. The transformation is a more profound developmental shift, where situations and dilemmas challenge our underlying assumptions and beliefs about the world. Transformative learning changes perspectives and relationships, laying the foundation for personal growth and innovation. It requires curiosity, attention, and courage. Adult learners embrace transformation if they feel the goals are worth attaining and they have control over the learning process.10 Table 2 outlines what to expect from transformative and incremental learning.

Table 2. Incremental versus transformative learning: what to expect.11

| Incremental learning | Transformative learning | |

| Personal value | Knowledge and skills | Purpose and presence |

| Organisational value | Alignment and preparation | Innovation and empowerment |

| Space for learning | Boot camp | Playground |

| Source of learning | Experts (models) | Experience (moments) |

| Work required | Deliberate practice | Reflective engagement |

| Marker of progress | Approaching ideals (closing the gap) | Redefining ideals (making room) |

| Aim of process | New action (a better way) | New meaning (a better why) |

| Role of supporters | Focusing practice | Inviting interpretation |

| Effect on power structure and culture | Affirmation | Subversion |

How can we inspire transformational learning in the workplace? Here are a few examples:

- An Indigenous patient discharges against medical advice. The supervising consultant asks their resident medical officer (RMO) to spend time with the ward social worker and Indigenous liaison officer to understand more about this patient’s situation. They work with the patient to find a compromise to ensure ongoing care is provided within the individual’s context of holistic health. The RMO is encouraged to discuss their learnings at handover the following day.

- A consultant has a relationship with a national patient organisation and involves their training registrar. During the year, the registrar orientates a patient advocate into a hospital working group, authors an article for patients about how to navigate the healthcare system and helps develop an online patient information resource.

- A team-building exercise is planned between midwives and obstetricians. They debate ‘Caesarean section on demand should be freely available in public hospitals.’ The midwives must present the affirmative argument and the obstetricians the negative.

Transformative learning more commonly comes from everyday activities, but the key is to recognise the opportunity as it presents, to slow down and make space for it.

Steps of transformative growth include four stages, described by Petriglieri.12

- Note the experience. How did it make you feel? What happened when you reacted differently, or your prior beliefs were challenged?

- Voice what happened. Discuss with others and see what their response is. What patterns do you notice? Reserve judgment and describe it, keeping your mind curious.

- Interpret the experience. Why did it go the way it did? Avoid usual thinking, eg. ‘because we’ve always done it that way’ or traditional relationships and structures. What novel interpretations could explain it? What are the implications for future situations: both similar and dissimilar? What did you learn?

- Own it. How does the experience fit with your prior personal beliefs? Now bring the past and the future into the conversation. What does it mean for the relationships involved and the team culture? How can you build confidence in new ways?

Online learning and social media

The role of e-learning for the lifelong learner has yet to be established, despite early adoption by the medical profession for CPD activities. Described benefits include the flexibility of self-paced learning, including case studies, ‘just-in-time’ knowledge and a systematic and logical approach from simple to complex information delivery. Challenges include self-discipline requirements from learners and an abundance of poor evidence-based education and training. E-learning is a time-, cost- and labour-intensive approach;13 however, the physical restrictions of the coronavirus pandemic have made it more common – if not more popular – than face-to-face conference events for CPD.

Doctors’ use of social media to supplement previously described learning approaches is well described, especially Twitter as a resource for dissemination, disruptive peer review and FOAMed – free open access medical education.14 The Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons reports using a Master’s Program closed Facebook group dedicated to sharing surgical video clips for peer review and feedback.15 The evidence for its use remains descriptive in nature.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that as the context of medical practice evolves further, our approaches to lifelong learning will adapt. Currently, expectations of the breadth of skills required for medical practice have outpaced evidence to inform the best resources and methods for lifelong learning. A priority for trainees and lifelong specialist practice is to continue to develop non-technical skills, including a deeper understanding of complexity science, metacognition, meta-learning and the importance of mental flexibility for personal and professional growth.

References

- Story ES. A brief history of the specialties from Federation to the present. Med J Aust. 2014;201(1): S26-S28

- Launer J. Complexity made simple. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94:611-2.

- Haupt J. Applying complexity science to health and healthcare. Plexus Institute. 2003. Available from: amee.org/getattachment/AMEE-Initiatives/ESME-Courses/AMEE-ESME-Online-Courses/Leadership-Online/ESME-LME-Resources/Applying-Complexity-Science-to-Health-and-Healthcare.pdf

- Aboulsoud S, Filipe HP. CPD and lifelong learning: a call for an evidence-based discussion. MedEdPublish. January 2019. Available from: doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000001.1

- Berkhout J, Helmich E, Teunissen P, et al. Context matters when striving to promote active and lifelong learning in medical education. Med Ed. 2018;52:34-4.

- Sagasser M, Kramer AWM, Fluit C, et al. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;2(4):931-49.

- Berkhout J, Helmich E, Teunissen P, et al. Context matters when striving to promote active and lifelong learning in medical education. Med Ed. 2018;52:34-4.

- Gostelow N, Gishen F. Enabling honest reflection: a review. Clini Teach. 2017;14(6):390-6.

- Veno M, Silk H, Savageau JA, et al. Evaluating one strategy for including reflection in medical education and practice. Fam Med. 2016;48(4):300-4.

- Rashid P. Surgical education and adult learning: Integrating theory into practice. F1000Res. 2017;6:143. doi:10.12688/f1000research.10870.1

- Petriglieri G. Learning for a living. MIT Sloan Management Review. 2019. Available from: sloanreview.mit.edu/article/learning-for-a-living.

- Petriglieri G. Learning for a living. MIT Sloan Management Review. 2019. Available from: sloanreview.mit.edu/article/learning-for-a-living.

- Regmi K, Jones L. A systematic review of the factors – enablers and barriers – affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC Medical Education. 2020;20:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02007-6

- Mandrola J, Futyma P. The role of social media in cardiology. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2020;30:32-5.

- Jones D, Stefanidis D, Korndorffer JR, et al. SAGES University MASTERS Program: a structured curriculum for deliberate, lifelong learning. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3061-71.

Leave a Reply