As a clinician, medical educator and avid user of social media and online resources, I have previously published a piece called Hippocrates would be on Twitter1 and so was asked to write this piece article. My opinion, supported by growing evidence, is that Dr Google is used by almost all our patients, students and peers in some way, often enhancing doctor-patient interactions. Thus, it is not about overcoming Dr Google but accepting it exists and indeed harnessing it for good. I’d also argue it is about thinking ahead to what might come after Dr Google, such as applications of artificial intelligence, so the medical and healthcare professions can have a greater influence from inception.

It is standard to be taught best practice with regards to traditional science communication at medical school, including critical appraisal of scientific literature. I think we’d all agree this is a vital and lifelong skill we need as clinicians, scientists and educators to provide the best evidenced-based care for our patients, forward scientific knowledge in our field of women’s health and educate future generations of those providing O&G care.

As with traditional information sources, like scientific papers, we have a responsibility to

- understand how and why online medical searches are done,

- educate our trainees, students and patients on how to identify online information and misinformation and

- use Dr Google with our patients, trainees and students in a responsible way, and ideally

- co-design and review information with patients, trainees and peers.

Hopefully this article provides some evidence, food for thought and practical tips.

Democratisation of information

The world wide web, or internet, came into being not that long ago, in the 1990s, forever changing accessibility to information and each other. This was information that was previously only held in encyclopedias, libraries or by experts like us. As access to the internet has become more prevalent, so too has access to information – making it accessible virtually instantaneously – to almost anyone, anywhere. The impact on access to health information for those living in rural, regional and remote Australia cannot be underestimated.

In 1996, just 1.6% of Australians had access to the internet at home; by 2015, this had increased to 86%.2 As of 2022, nearly all Australian adults (99%) have access to the internet. 91% of Australian adults have a home internet connection, and three-quarters of these have an NBN connection.3 This is in addition to the many smart phone and tablet devices used to download data. In the first half of 2021, almost all (98%) older Australians aged 55+ used the internet, up from 76% in 2019, prior to COVID-19 lockdowns.4

Dr Google

Google was founded in 1998, a year before I graduated from medical school. The use of ‘Dr Google’ and the internet for health information wasn’t included in my medical school curriculum. At the time, as in previous generations, it was conceivable that doctors could learn and know everything and be the one source of truth for our patients.

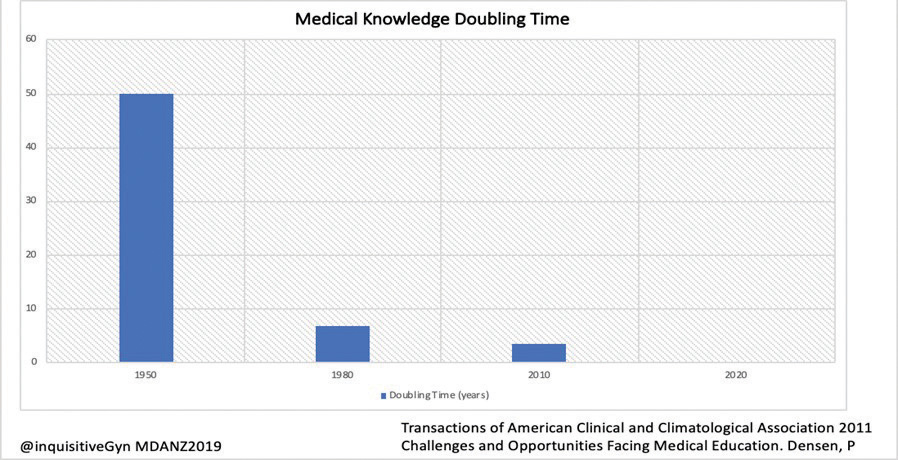

In 1950, medical knowledge had an estimated doubling time of 50 years. In 2000, when I was an intern, that figure was closer to 10 years.There has been an ongoing exponential increase in knowledge, and prior to COVID-19 the projected doubling time in 2020 was just 73 days.5 That figure has almost definitely shortened with the avalanche of information we have all experienced since the pandemic began, with WHO calling it an ‘infodemic’.6 This has made it impossible to learn and know everything without a Google or other search!

Much has been said about ‘Dr Google’ in the medical and health literature in the past twenty or so years. Doctors tend to respond to online searches by their patients in one of three ways:

- by reacting defensively and asserting their expert opinion;

- by collaborating with the patient to analyse the information ; and

- by guiding the patient to reliable health information websites.7 8

Whilst there is valid concern of the veracity of information patients may find, there is a growing body of evidence that patients seeking online information improve their knowledge and self-advocacy.8 Of note, women are more likely than men to seek health information online.9 Evidence has shown that more patients are searching the internet prior to consultations for answers to symptoms and to prepare for a consultation.10 11 12 Reassuringly, several Australian and international studies have demonstrated that internet searches do not undermine the doctor-patient relationship, and well-informed patients contribute positively to interactions.13

The Australian Women and Digital Health Project is one of the most recent studies conducted in Australian women, published in 2018. The study demonstrated that women are highly engaged with online health information regardless of their age or education level.14 The Australian Women and Digital Health Project found that ‘participants were engaging actively, creatively and critically with online information, using it in a number of different ways to complement rather than supplement medical advice’.15

With regards to the ‘defensive reaction’ there are memes and mugs stating ‘don’t confuse your Google search with my medical degree’ yet most – dare I say all – doctors have used Google to search for information. We need to be able to set aside our own ego and bias and work with patients to ensure they have best knowledge and the tools to critically analyse them. There is a more recent meme equating to ‘don’t confuse your one-hour lecture with my lived experience’. Whilst specialist training is well beyond a one-hour lecture, I hope the point is clear. For best patient care, we need to work together with our expertise and the patient’s lived experience.

Scepticism about Dr Google is understandable given concerns about lack of regulation of information on the internet and lack of context for how a patient has consumed that information. Whilst internet searching can lead to conflict if the patient values internet- derived information above that of the doctor, causing them to ignore their advice 16 17 evidence shows this occurs rarely. Evidence from those searching before attending ED or a GP consultation has shown a positive impact on the doctor-patient relationship, particularly for those with greater e-health literacy, and was unlikely to cause patients to doubt the diagnosis by a practitioner or to affect adherence to treatment.18 19 20

Healthy scepticism should always exist, including of traditional scientific information, but defensive reactions can harm a patient-doctor interaction. We can, and must, move past this and work with patients to view and analyse this information together – by directly asking our patients what they already know, where they have learned this information and trusting they understand that not everything on the internet is fact or complete. Evidence and common sense dictates that most people do know this.

Health literacy can be defined as ‘the ability of an individual to obtain and translate knowledge and information to maintain and improve health in a way that is appropriate to individual and system contexts’.21 Digital literacy is described as ‘the ability to identify and use technology confidently, creatively and critically to meet the demands and challenges of living, learning and working in a digital society’.22 Digital and health literacy are key factors in understanding information and how to use it, as well as reducing the spread of misinformation.23

Misinformation

Along with ‘Dr Google’, terms like misinformation and disinformation have become widely used and understood. Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information presented as fact, either intentionally or unintentionally. Disinformation is more sinister and is a subset of misinformation, that which is deliberately deceptive.24 It’s the misinformation and disinformation that probably most result in frustration and a defensive reaction. It’s also essential we know if patients have encountered misinformation and disinformation to correct and counter it. Equally, misinformation and disinformation are not new. They have existed for centuries in the form of word of mouth, family advice and from mainstream media. Online sources and Dr Google have merely amplified access and proliferation.

A solution – ask, have you searched online? What did you find?

An alternative to a defensive reaction is to teach ourselves and our patients how to critically appraise online information and encourage critical thinking with regards to all information sources, whether online, from friends and family or from scientific literature. Embracing this stance can improve health and digital literacy for us all – which can only be a good thing. I would encourage us all to acknowledge Dr Google with patients and discuss their online searches with them as well as direct them to information.

Democratisation, diversity and inclusion

Using ‘Dr Google’ with patients democratises information and assists us including all patients. By embracing ‘Dr Google’, we can harness it for good by using its many features including Google Translate. Sites for cultural, demographic and language groups, including First Nations, LGBTQI+ groups, as well as information from other countries can all be accessed. Thus, Google can improve access to information created for and by those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Whilst Google Translate is imperfect and does not have all languages, it is another accessible online tool that can be used and hopefully will improve in future. In this way we can ensure information is inclusive for our patients’ many diverse needs and truly equitable.

Our obligation as educators/clinicians

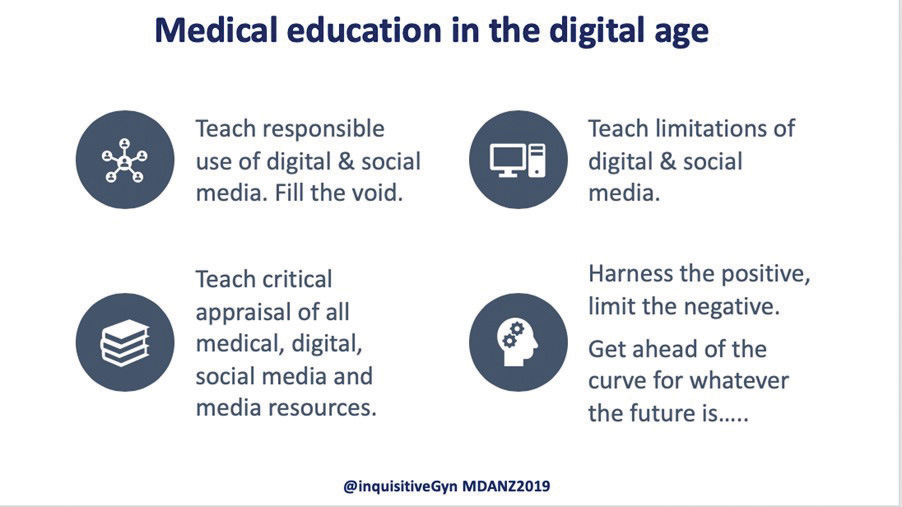

Despite this explosion in knowledge and increased use and accessibility of the internet, creation and use of online medical and health information, how to combat misinformation and disinformation is still not routinely taught in medical schools or training curricula. Given the evidence suggests we do not need to overcome ‘Dr Google’, but instead harness it for good, we need to know how to access and identify the best information and effectively counteract misinformation and disinformation with our students, trainees and patients.

As mentioned, few existing healthcare curricula or courses focus on online information and curation. There are programs in media training for science and health professionals and these often include online science communication and social media. Given misinformation is most proliferated on social media, the few existing courses and frameworks for critical appraisal of online information often apply across both these areas as if in a Venn diagram.

UNESCO Handbook for Journalism Education and Training

One standout existing free resource on information and disinformation is The Handbook for Journalism Education and Training created by UNESCO.25 Whilst it is specific to journalism, not healthcare, it is an excellent resource and arguably provides an excellent framework.

The curriculum, which has a pedagogical heuristic approach that encourages lived experience or case examples, could easily be adapted for healthcare and our specific context. The modules cover topics including information, disinformation, fact checking 101, digital technology and social media verification.26

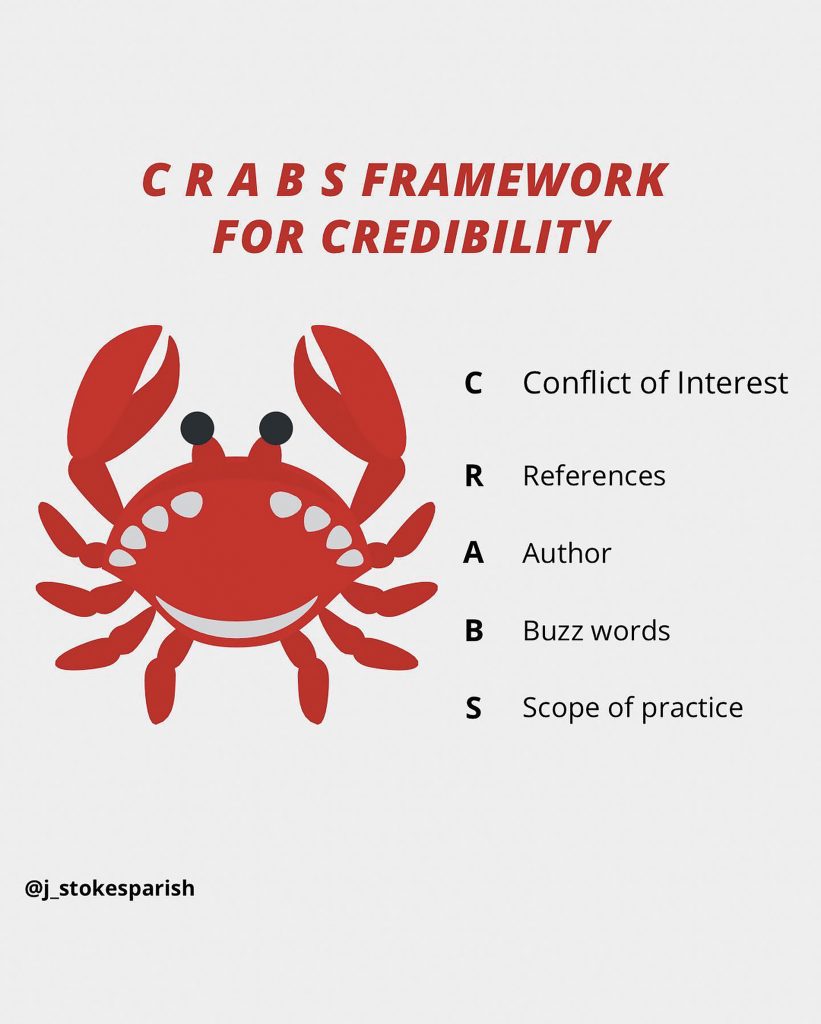

CRABS framework

A framework to equip the public to spot red flags in health information online using the mnemonic CRABS27 has been developed by Australian critical care nurse and academic, Dr Jessica Stokes-Parish. The framework aims to leverage evidence-based educational strategies for empowering the public to determine truth from fiction.

C – Conflict of interest

R – References

A – Author

B – Buzz words

S – Scope of practice

The framework is intended to be applied as an initial guide and does not replace a full critical appraisal.28

Conclusion

Humans have not and cannot change our cognitive ability to learn more. We therefore need to maximise our ability to curate and access knowledge. Just as we use Google to obtain information, so do our patients, their families, our trainees and students. Yes, that means there is access to both information and misinformation. As with other skills taught during medical school and specialist training to critically appraise scientific and medical literature, we need to learn how to address misinformation and disinformation online for ourselves and with our patients. We need to learn how to harness the internet for good, and conduct research to understand its role in women’s health. We also need to embrace and teach e-health literacy, critical thinking and finally co-design information and training of these skills with our patients and each other.

References

- Szabo RA. Hippocrates would be on Twitter. MJA. 2020;213(11):506-7. e1.

- Hill MG, Sim M, Mills B. The quality of diagnosis and triage advice provided by free online symptom checkers and apps in Australia. MJA. 2020;212(11):514-9.

- Authority A-ACaM. Communications and media in Australia: How we use the internet. 2021.

- Authority A-ACaM. Communications and media in Australia: How we use the internet. 2021.

- Densen P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 2011;122:48.

- Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):676.

- Cocco AM, Zordan R, Taylor DM, et al. Dr Google in the ED: searching for online health information by adult emergency department patients. MJA. 2018;209(8):342-7.

- Tan SS-L, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(1):e5729.

- Baazeem M, Abenhaim H. Google and women’s health-related issues: what does the search engine data reveal? Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 2014;6(2).

- Cocco AM, Zordan R, Taylor DM, et al. Dr Google in the ED: searching for online health information by adult emergency department patients. MJA. 2018;209(8):342-7.

- Van Riel N, Auwerx K, Debbaut P, et al. The effect of Dr Google on doctor–patient encounters in primary care: a quantitative, observational, cross-sectional study. BJGP open. 2017;1(2).

- Maslen S, Lupton D. “You can explore it more online”: a qualitative study on Australian women’s use of online health and medical information. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):1-10.

- Cocco AM, Zordan R, Taylor DM, et al. Dr Google in the ED: searching for online health information by adult emergency department patients. MJA. 2018;209(8):342-7.

- Maslen S, Lupton D. “You can explore it more online”: a qualitative study on Australian women’s use of online health and medical information. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):1-10.

- Maslen S, Lupton D. “You can explore it more online”: a qualitative study on Australian women’s use of online health and medical information. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):1-10.

- Cocco AM, Zordan R, Taylor DM, et al. Dr Google in the ED: searching for online health information by adult emergency department patients. MJA. 2018;209(8):342-7.

- Tan SS-L, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(1):e5729.

- Cocco AM, Zordan R, Taylor DM, et al. Dr Google in the ED: searching for online health information by adult emergency department patients. MJA. 2018;209(8):342-7.

- Van Riel N, Auwerx K, Debbaut P, et al. The effect of Dr Google on doctor–patient encounters in primary care: a quantitative, observational, cross-sectional study. BJGP open. 2017;1(2).

- Wald HS, Dube CE, Anthony DC. Untangling the Web—The impact of Internet use on health care and the physician–patient relationship. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;68(3):218-24.

- Liu C, Wang D, Liu C, et al. What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Family Medicine and Community Health. 2020;8(2).

- Coldwell-Neilson J. Unlocking the code to digital literacy: Department of Education, Skills and Employment; 2020.

- Navigating Credibility of Online Information during COVID-19: Using mnemonics to equip the public to spot red flags in health information online. JMIR Preprints. 2022.

- Ireton C, Posetti J. Journalism, fake news & disinformation: handbook for journalism education and training: Unesco Publishing; 2018.

- Ireton C, Posetti J. Journalism, fake news & disinformation: handbook for journalism education and training: Unesco Publishing; 2018.

- Ireton C, Posetti J. Journalism, fake news & disinformation: handbook for journalism education and training: Unesco Publishing; 2018.

- Navigating Credibility of Online Information during COVID-19: Using mnemonics to equip the public to spot red flags in health information online. JMIR Preprints. 2022.

- Navigating Credibility of Online Information during COVID-19: Using mnemonics to equip the public to spot red flags in health information online. JMIR Preprints. 2022.

Leave a Reply