The Solomon Islands is Australia’s close neighbour, only a 3.5-hour plane trip away from Brisbane. It is a beautiful country spread across an idyllic archipelago of over 990 islands with a rich history and strong culture. Despite its beauty, it faces significant geographical, socioeconomic and cultural barriers to achieving health equity. I was fortunate enough to spend six months in Honiara in 2018 as an Australian Volunteers International (AVI) volunteer as a Senior O&G registrar at the National Referral Hospital (NRH). NRH is the only tertiary referral hospital servicing a population of over 600 000. Unsurprisingly, the O&G department is the busiest in the hospital, seeing over 70% of the hospital’s admissions and up to 6000 deliveries a year. The department is led by Dr Leeanne Panisi, an inspirational leader and the only female O&G consultant in the country. Dr Panisi is supported by only three other consultants and limited junior medical and midwifery staff – a fraction of the human resources a tertiary hospital in Australia or New Zealand would have, and far less than what is needed.

The morning handover is where the events of the last 24 hours are summarised for the whole team – the total births, caesarean sections, maternal deaths, maternal morbidity, neonatal deaths and stillbirths. The stories and numbers are sobering, particularly when discussing stillbirths. Stillbirth is a significant global public health issue, with approximately 98% occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), like the Solomon Islands.1 2 3 Each of these lives lost results in a huge emotional burden for these women, families, and communities. For Dr Panisi and her team, these stories are all too familiar. Like many of its counterparts in the Asia-Pacific, the Solomon Islands has poor perinatal outcomes, with a recent study showing a high rate of preventable maternal mortality4 and an estimated stillbirth rate of 17.6 per 1000 births in 2015 from World Health Organization (WHO) data. Whilst most stillbirths occurring in LMICs are preventable, progress in reducing these numbers has been poor and under-prioritised compared to other perinatal outcomes5 6 and there has been no previous targeted research investigating preventable causes of stillbirths in the Solomon Islands.

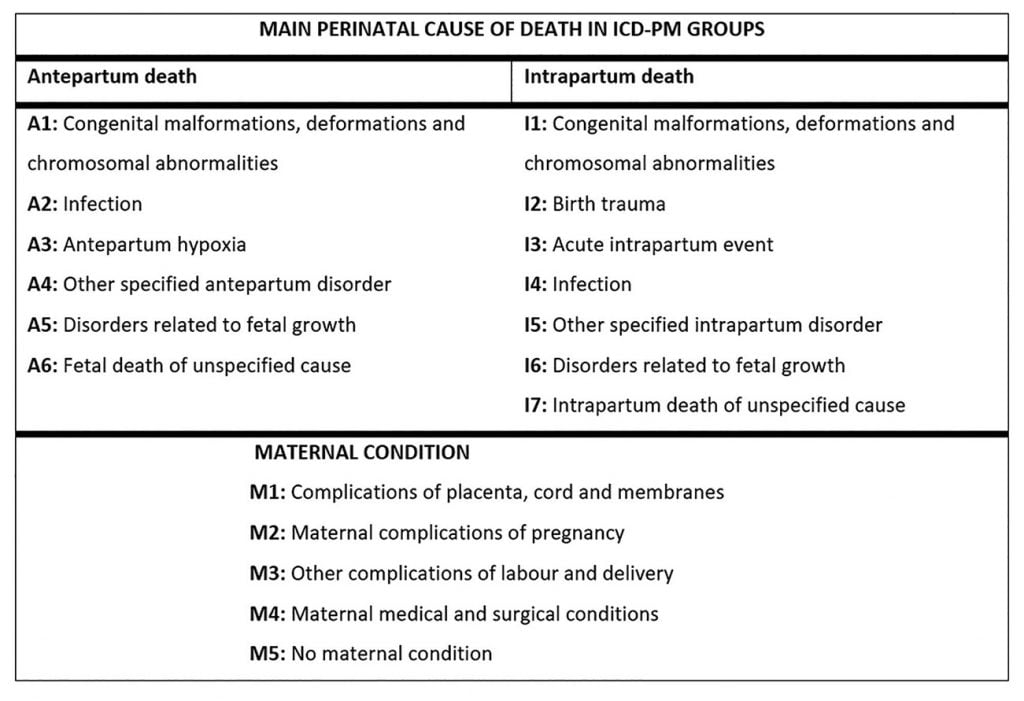

In many LMICs, the lack of diagnostics tools makes ascertaining timing and cause of death especially challenging.7 8 9 As a result, many countries do not have a national registration system for perinatal deaths, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region.10 11 12 While stillbirths are not nationally classified, monthly audits at NRH presented an opportunity to glimpse the state of stillbirth in the country. Thus, with the aim of identifying key opportunities for intervention, we conducted a retrospective review in 2019 investigating all stillbirths (those ≥20 weeks estimated gestation or >500g birth weight) occurring at NRH over two years (2017 and 2018). Using the WHO International Classification of Diseases applied it to the perinatal period (WHO ICD-PM) (Table 1), we identified timing of death, primary cause and linked each death with the main contributing maternal condition.13 14

Table 1. The ICD-PM stillbirth classification system.

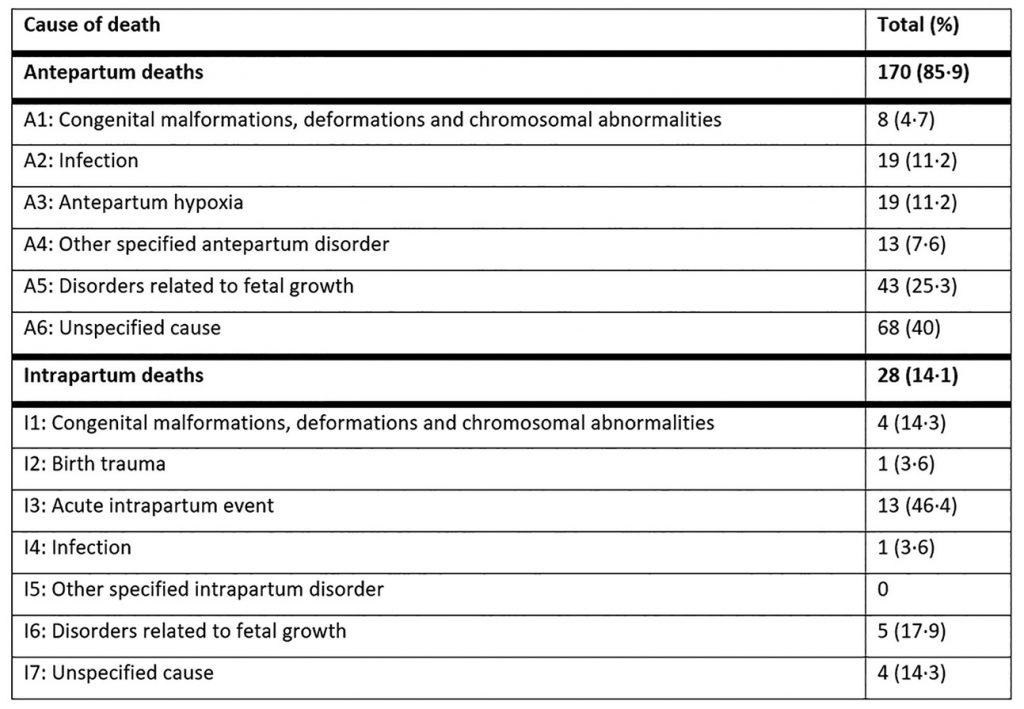

With 341 stillbirths and 11 056 births over two years, we uncovered a high institutional incidence of 30.8 per 1000 births.15 This is nearly double that of its closest neighbour, Papua New Guinea (15.9 per 1000 births, nation-wide) and a stark contrast to the stillbirth rates of Australia (6.8 per 1000 births) and New Zealand (8 per 1000 births).16 17 Whilst suspected cause of death was available for 198 stillbirths (Table 2), 58% of case files were missing, highlighting the difficulties with accurate data collection in LMICs. The majority of women were multiparous (62%). We deemed 72% to be preventable – those with an estimated gestation over 28 weeks, birthweight >1500g and no congenital abnormalities. There were five stillbirths associated with a maternal death. Most fetal deaths occurred antenatally (86%) and 80% occurred in the third trimester. Unsurprisingly, risk factors, such as low birthweight (<2500g) and preterm birth (<37 weeks estimated gestation) were common (59% and 62%, respectively). Hypertensive disorders and infection were present in almost half of antenatal stillbirths with 10 fetuses showing overt signs of congenital syphilis. Although we found almost 80% of mothers attended at least one antenatal visit, sadly, many simple interventions were completely lacking. Only a quarter of women who experienced a stillbirth received an early ultrasound, discussions of reduced fetal movements were not documented in half of all cases and haemoglobin levels were only recorded in 56%. Only 90 women (63%) were tested for syphilis and of those who tested positive, only 30% completed treatment. These findings suggest many crucial gaps in care. But they also provide hope that simple, cost-effective interventions may have the potential to significantly reduce stillbirths nationwide.

Table 2. Causes of antenatal and intrapartum stillbirth (ICD-PM classification) at the National Referral Hospital over a two-year period of 2017–2018 for all cases of stillbirth where cause was documented (n-198).

Importantly, progress is being made. The Solomon Islands Ministry of Health and the WHO have recently launched an updated national Antenatal Care Package, which emphasises interventions for many of these issues and provides a standard expected quality of care. It incorporates focused health worker education and resource provision, such as improved access to antenatal ultrasounds and point-of-care syphilis and haemoglobin testing. This initiative acknowledges the socioeconomic return of investing in stillbirths18 and is a fundamental step in reducing the burden of stillbirths in the Solomon Islands.

Without a national surveillance system for stillbirths, the true magnitude of perinatal deaths remains under-reported and under-investigated, as we have only included data from the hospital setting in this study. Our study was also limited by its retrospective nature and incomplete data. Alarmingly, the disruption of health systems as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic will potentially increase these losses, as has already been found in other regions.19 20 Furthermore, Honiara has suffered recent disruptions to service provision with civil unrest. Despite this, Dr Panisi and her team continue to work tirelessly and advocate for the women of the Solomon Islands. We remain hopeful that we may be able to uncover why stillbirths are occurring and what can be done to prevent them with ongoing research efforts. Only with accurate data can we hope to inform public health reforms and tackle this ongoing global issue.

Further reading

- De Silva M, Panisi L, Maepioh A, et al. Maternal mortality at the National Referral Hospital in Honiara, Solomon Islands over a five-year period. ANZJOG. 2020;60:183-7.

References

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4:e98-e108.

- Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016;387:587-603.

- McClure EM, Saleem S, Goudar SS, et al. Stillbirth rates in low-middle income countries 2010 – 2013: a population-based, multi-country study from the Global Network. Reprod Health. 2015;12 Suppl 2:S7.

- International Stillbirth Alliance Collaborative for Improving Classification of Perinatal D, Flenady V, Wojcieszek AM, et al. Classification of causes and associated conditions for stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;22:176-85.

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4:e98-e108.

- Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016;387:587-603.

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4:e98-e108.

- Patterson JK, Aziz A, Bauserman MS, et al. Challenges in classification and assignment of causes of stillbirths in low- and lower middle-income countries. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:308-14.

- International Stillbirth Alliance Collaborative for Improving Classification of Perinatal D, Flenady V, Wojcieszek AM, et al. Classification of causes and associated conditions for stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;22:176-85.

- Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016;387:587-603.

- Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Saleem S. Improving pregnancy outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2018;15:88.

- McClure EM, Garces A, Saleem S, et al. Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research: probable causes of stillbirth in low- and middle-income countries using a prospectively defined classification system. BJOG. 2018;125:131-8.

- International Stillbirth Alliance Collaborative for Improving Classification of Perinatal D, Flenady V, Wojcieszek AM, et al. Classification of causes and associated conditions for stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;22:176-85.

- Allanson ER, Vogel JP, Tuncalp, et al. Application of ICD-PM to preterm-related neonatal deaths in South Africa and United Kingdom. BJOG. 2016;123:2029-36.

- De Silva M, Panisi L, Manubuasa L, et al. Preventable Stillbirths in the Solomon Islands – a hidden tragedy. Commentary. The Lancet Regional Western Pacific. 2020;5.

- De Silva M, Panisi L, Manubuasa L, et al. Preventable Stillbirths in the Solomon Islands – a hidden tragedy. Commentary. The Lancet Regional Western Pacific. 2020;5.

- World Health Organization Statistic – Stillbirth (Western Pacific Region). Vol. 2020: World Health Oragnization, 2015.

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4:e98-e108.

- Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8:e901-e8.

- Ashish K, Gurung R, Kinney MV, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(10):e1273-81

Leave a Reply