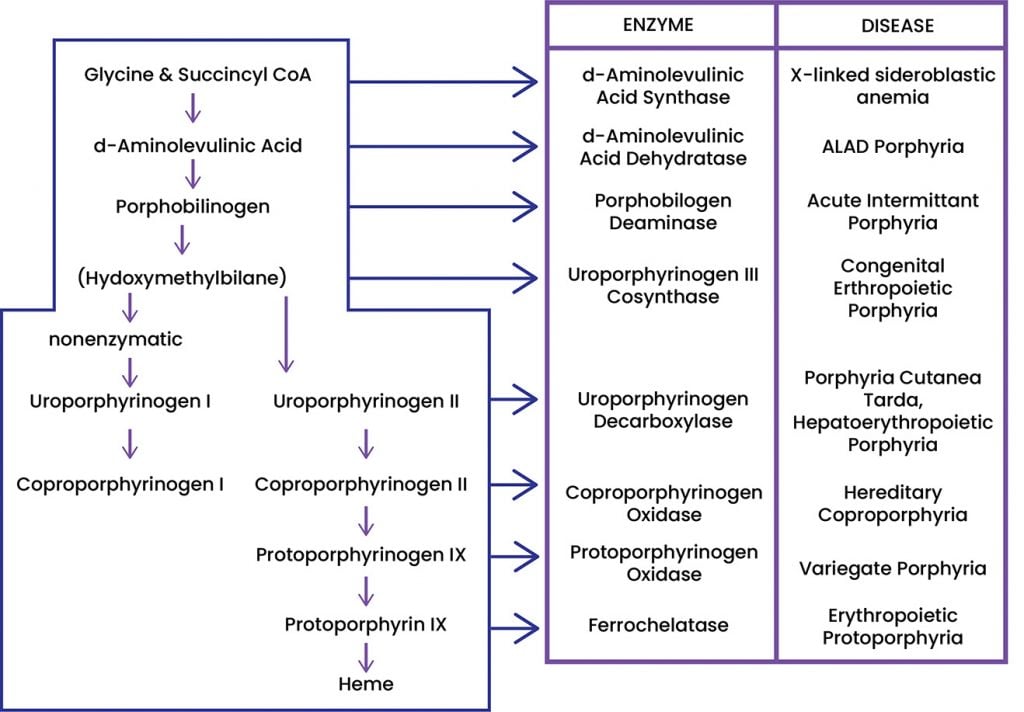

The porphyrias are a group of rare genetic metabolic diseases that are often misunderstood and rarely diagnosed. They are characterised by changes to the heme biosynthesis pathway. The different subtypes of porphyria are often confused by medical professionals and patients alike. There are eight types of porphyria, and they are broken down into acute and cutaneous subcategories.

Figure 1. Heme Biosynthesis Pathway.

The Acute Hepatic Porphyrias (AHP); Acute Intermittent Porphyria, Variegate Porphyria, and Hereditary Coproporphyria are most typically associated with abdominal pain and other symptom clusters that patients might report to a GP, gastroenterologist or O&G. This article will be focusing on the experiences of people who have been diagnosed with AHP rather than Cutaneous Porphyria.

The acute porphyrias present as acute attacks that are triggered by a variety of environmental and pathological factors. Symptoms tend to be worse in women than men and attacks can be life-threatening if not promptly identified and treated. In women, attacks may be associated with the luteal phase of menstruation. The word acute refers to the presentation of this type of porphyria which comes on in acute attacks, typically lasting days to weeks; however, some patients can develop chronic pain postulated to be related to nerve damage from repeated acute attacks.

I represent the Australian Porphyria Association; I have been the President of the Association since 2015. The Association is in the process of lobbying for access to GIVLAARI® (givosiran), Normosang® (human hemin) and SCENESSE® (afamelanotide). Increased access to treatments has been a key objective for the association for a number of years. Doctors have been key in this process, running clinical trials and partnering with consumer groups to improve patient health outcomes. During my time at the association, I have heard the stories of many men and women who have AHP. It is always quite interesting to hear their stories, they often sound like they are reading from the same script. For this article I will focus on the stories of the women that contact us.

Usually, people experiencing AHP for the first time will present between ages 18 and 35. People with AHP typically experience considerable non-localised abdominal pain, nausea, neurological changes, light sensitivity, and reddish-brown urine (that contains no blood). The most typical time to have an onset of AHP is after puberty, trauma, or pregnancy.

The story of women with AHP is common. The first thing patients tell me is that they saw their GP for their unexplained abdominal pain and other seemingly random symptoms. Their GP will usually refer them to a gynaecologist who will then often perform an explorative laparoscopy to look for endometriosis. If nothing is found, it is common for them to have their appendix and/or gallbladder removed. Unfortunately, during this surgical exploration process, they typically become more unwell despite having no specific findings on usual tests, further confusing the clinical picture. This can be due to the use of contraindicated medications or fasting from surgery. Once usual surgical and diagnostic imaging options have been explored and nothing has been found, they are discharged without a diagnosis or management plan. Those that are persistent will then go back to their GP who then refer them onto a psychiatrist for assessment. This can be incredibly distressing for the patients who are then told that the symptoms they are experiencing are ‘all in their head’, but treatable peripheral drivers have not been excluded. Patients are typically misdiagnosed with an array of conditions before the correct diagnosis is established.

Dr Gayle Ross, the head clinician at the Royal Melbourne Hospital Porphyria Clinic recently came across a new case of hereditary coproporphyria (HCP). A 28-year-old woman presented to the porphyria clinic at Royal Melbourne hospital with a 4-year history of recurrent episodes of generalised, severe abdominal pain. It flared premenstrually and was associated with nausea and vomiting. She had a rash on her face consisting of sores with scabs. She had been extensively investigated for both gastrointestinal and gynaecological causes of abdominal pain and was being considered for a total colectomy. Porphyrin studies were ordered and were consistent with HCP. Given her ongoing episodes that caused incapacitation premenstrually, she was treated with prophylactic haem arginate, monthly via a portacath for several years, with suboptimal control. She had recurrent symptoms that included poor coordination and falls. She became more complicated when she attempted IVF conception with resulting flares due to the hormones, and this was ultimately unsuccessful. Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) Analogues were not tolerated. At the age of 44, she underwent a hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy to induce menopause in order to stop her episodes of abdominal pain. She is now on low-dose hormone replacement therapy and her porphyria symptoms have almost completely resolved. She is being managed for osteoporosis.

Without the correct diagnostic testing, this can be the end of the journey to diagnosis for patients. Many women can have a delay of up to ten years until the correct diagnosis is confirmed. Those who are lucky enough to have a doctor who is knowledgeable about porphyria have a shorter diagnosis period and can avoid many years of permanent physical damage and emotional distress.

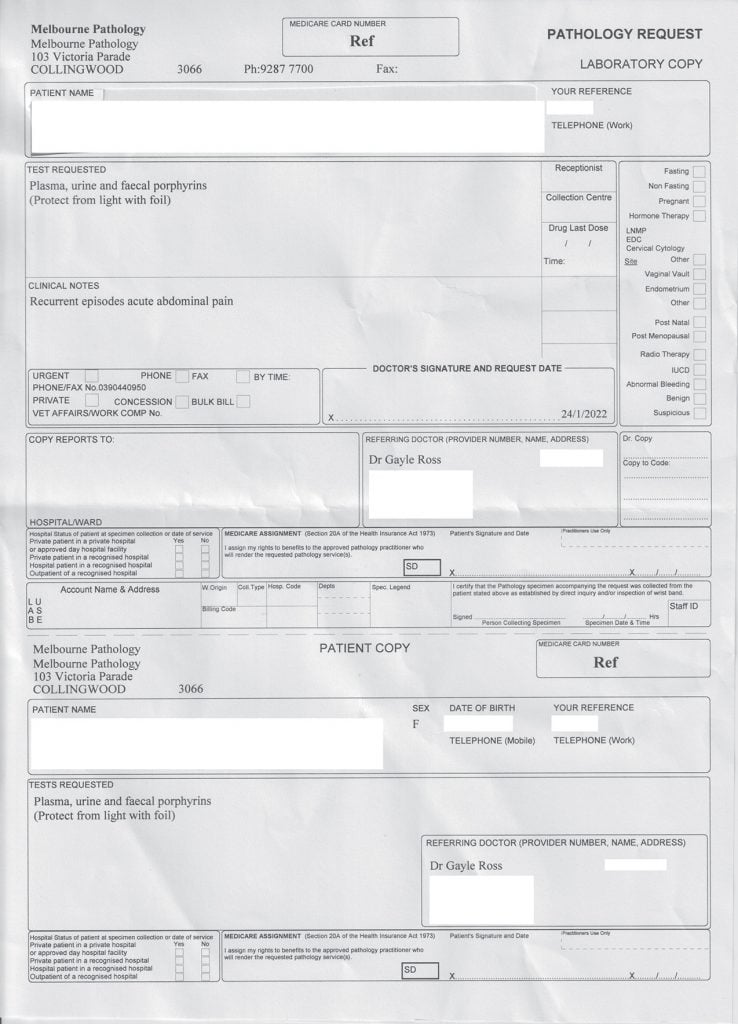

The good news is that testing for porphyria is straightforward and inexpensive. The testing for porphyria involves a simple blood, urine, and faecal test: write on the pathology request ‘porphyrin studies, porphyrin screen’. See the below pathology form for an example.

Figure 2. Example pathology form.

All samples need to be protected from light by covering the specimen jar/tube with aluminium foil and can be collected at any hospital or pathology clinic. Porphyria can only be confirmed by positive biochemical testing, not by symptoms alone. The Medical Advisory Board of the Australian Porphyria Association recommends that all types of porphyria should be tested for in the screening test but recommend that any family history and symptoms are recorded on the pathology form. There is currently a lack of testing for AHP with only approximately 400 pathology tests for undiagnosed patients requested in Victoria annually. Given the very minimal cost, it is hard to imagine why someone might have expensive repeated CT imaging, recurrent emergency presentations and not a once-off inexpensive test.

If AHP was regularly tested for in people presenting to their GP or gynaecologist with persistent, unexplained abdominal pain, we would see the numbers of patients diagnosed increase. Experts in Australia have long expressed how underdiagnosed AHP is. It is estimated that there are over 500 patients that are currently undiagnosed in Australia and New Zealand.

Porphyria is underdiagnosed, and while there are some major centres that have clinics, we need more research into the disease. One of the questions that have perplexed doctors is the prevalence of HCP as the dominant subtype of AHP in Australia and New Zealand.

Porphyria patients can often struggle with being heard and listened to by medical professionals. Many patients tell me that they were labelled as ‘drug seekers’ or ‘attention seekers’ during and/or after their diagnosis. This could partly be due to the confusing and complicated way that they might present. They also may not have many changes to their pathology until the attack progresses to a life-threatening stage. In addition, AHP can affect people neurologically which might change their typical behaviour and they could be experiencing anxiety and brain fog due to the acute attack. Understanding and awareness of the disease are key drivers to help improve the care that these women receive. It is very important to listen to the patients and to be aware that they have probably had some negative and distressing experiences with health professionals before they walked into your room. Women will tell me how excited they were when either their GP or specialist understood their disease and were relieved they didn’t feel the need to explain it to them.

In O&G, consider porphyria in your patient who has unexplained abdominal pain, and perhaps multiple sensitivities to medicines or intolerance of the pill and other hormones. Know there are specific treatments available but that most of our knowledge comes from case series from specialised units. Depending on the genetics, women may choose IVF and PGD prior to pregnancy and consider contacting us to source the genetic counsellor and doctor with most experience in your area. Testing, listening and knowledge is key for the better treatment of women with AHP. If you were considering research in this area, there are many investigated areas that you could conduct research in. Some of these topics are:

- What proportion of women presenting to emergency departments have porphyria?

- What is the incidence of porphyria in patients with undiagnosed abdominal pain?

- How should a woman with AHP requiring contraception be counselled?

- Pregnancy outcomes in patients with AHP. How many have porphyria flares? Any implications for delivery?

- Can patients accurately tell whether their abdominal pain is porphyria versus alternative gynaecological diagnoses?

For more information, please go to the Australian Porphyria Association’s website or to watch the new educational video series that has been developed by leading Australian and New Zealand specialists and scientists in the field, see the Australian Porphyria Associations Facebook page.

Special thanks to Dr Marilla Druitt for assistance with this article.

Our feature articles represent the views of our authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), who publish O&G Magazine. While we make every effort to ensure that the information we share is accurate, we welcome any comments, suggestions or correction of errors in our comments section below, or by emailing the editor at [email protected].

References

- American Porphyria Foundation, 2020. Available from: https://porphyriafoundation.org/apf/assets/Image/patients/testing/enzymechart

- Klose RT. Porphyria. Magill’s Medical Guide (Online Edition), 2019. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=ers&AN=86194445&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Sohail QZ, Khamisa K. Acute porphyria presenting as abdominal pain in pregnancy. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2021;193(12):E419–E422. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202384.

- Edel Y, et al. The clinical importance of early acute hepatic porphyria diagnosis: a national cohort. Internal and Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine. 2021;16(1):133–9. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02359-3.

Leave a Reply