From the original technological invention of the forceps by the Chamberlen brothers in the 17th century,1 there has been continual development in obstetrics and gynaecology technology.

Technology we take for granted can allow more to be done for less cost, more to be done with less harm and more to be done than can be imagined. Technology is big business, in 2019, the global medical devices market reached a value of nearly $457 billion US dollars.2

This year marks 50 years of email. Although many of us curse our inboxes at times, email allows collaboration and real-time discussion, resulting in swift developments while saving trees.

Telehealth is clearly improving access and equity for rurally isolated families, to be able to access tertiary level advice in their own homes, but also reducing the cost from a half-day loss of productivity for a single medical appointment.

But with only 88% of Australia with mobile phone or internet access,3 4 we need to be mindful of this equity gap, and that those already disadvantaged, are not made more so.

Dr Michael Wynn-Williams operating in 2015.

Patient benefits

Women now have immediate access to up-to-date information about their health via the internet. They are able to connect with support groups and peer counselling via social media. There are apps for self-management and apps for new interventions, there is even an app to connect to a pelvic floor trainer, thefemfit.com.

Wearable devices are everywhere, telling you, and your provider, your physiology state every minute of the day. The ubiquity of wearables (and their data) are expected to aid the likes of Apple, Google et al in further enhancing their digital profile of you, your kids and probably your household cat. The ongoing land grab for peoples ‘big data’ has been in full swing for several years and only recently have governments sought some regulation and controls with debatable results. The rabbit hole we all may be heading into with this is less clear with the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI).

AI is currently seen in medicine with visual recognition in reading pathology and radiology films, performing advanced triage tasks and data prediction models. Where AI may lead us down from here asks several questions of how we manage healthcare and what we value: equity over efficiency? Safety over innovation? Disparities over invention? None of these answers are clear at this stage, but there is significant thought currently taking place around the world and how best to step into this new brave world. As obstetricians, there is a high degree of scrutiny of our work given the high stakes environment. Who should be accountable (or liable) when an AI system is involved in patient care? It is a question that is currently in its fetal stage of development.

Continued education benefits

No longer do we need to subscribe and wait for our quarterly journals to arrive. We can now set up a program like Read by QxMD, which will identify and notify you of articles, from a variety of journals, personalised to you. We can soon expect that AI will be an important tool in scouring medical journals to assist busy clinicians with acquiring new knowledge, new information and new opinions. Twitter is currently a wonderful tool where the convergence of humans and technology algorithms meet in both enlightening and disastrous ways, #Medtwitter. And for all of us time-poor, we can utilise commuting time by listening to medical podcasts that may keep us up to date, and review the latest published work while we sit back and take it in.

Training benefits

Where once we would gather around an operating table to catch a glimpse of the professor operating, we can now access repositories of surgical video sites from favourite local surgeons or international sites like WebSurg, entirely for free. These videos mean you can see exactly what they see with real-time commentary, pause and replay as necessary. Accompanied by laparoscopic trainers, both low and high fidelity, trainees and up-skilling consultants can learn within the safety of simulation.

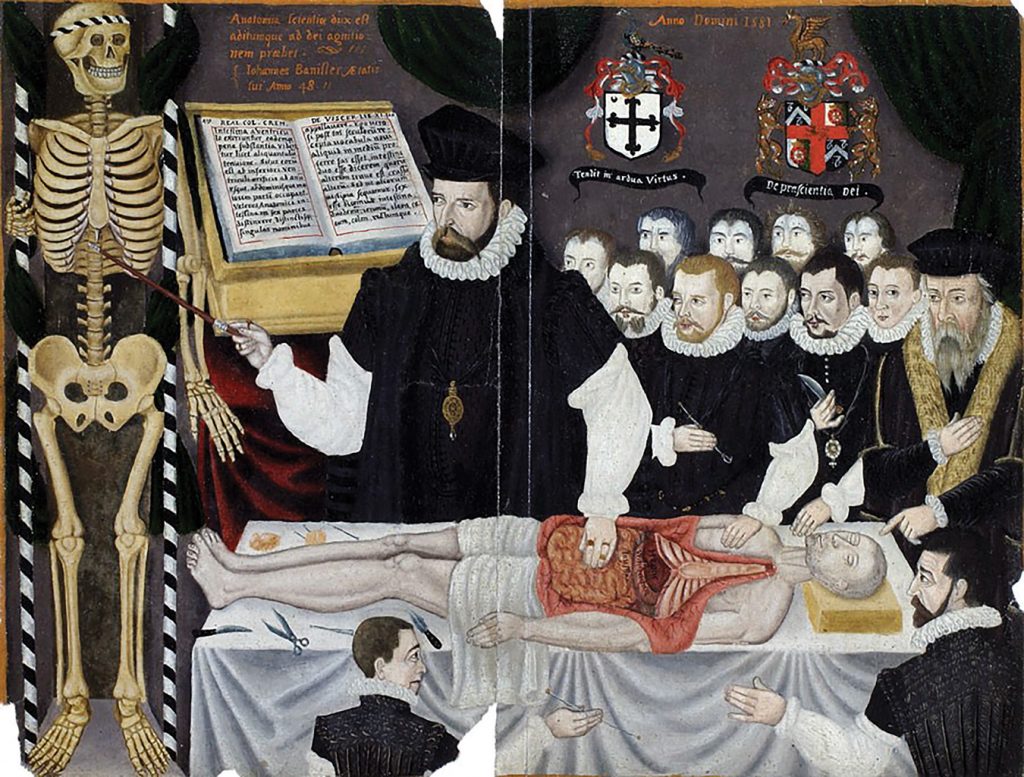

Master John Banister delivering an anatomical lecture.

Surgery made easier

We cannot forget that it was gynaecology that first developed laparoscopy, which has now progressed to single-port operative systems and the use of self-contained extraction systems meaning that 20cm specimens can be removed through a 3cm hole with knife morcellation or even a 12mm hole with a power morcellator.

Continuing improvements to equipment are producing better ergonomic devices. Surgical aides that we once dreamed of are available. For example, IGC fluorescence enhancement is improving lymph node dissection, and illuminating urethral catheters are a pelvic surgeon’s godsend.

I am always reminded whenever I watch our general surgery colleagues, that we don’t always utilise even the simple technologies at hand. Like the anti-fatigue mats to stand on, or putting on a headlamp. The surgeons also make better use of the external retractor systems when we struggle through our self-retainer.

Care made easier

Europe has licenced the use of continuous glucose monitoring and insulin pumps for gestational diabetes. These devices are so popular and convenient now, individuals are building and programming their own insulin regimens.

Once bulky $20k machines are reduced to an ultrasound probe that fits in your pocket and connects to your phone.

Platforms like Surgical Performance makes surgical logging and auditing effortless. It tracks your complications and benchmarks you against your fellow surgical community.

The artificial placenta,560 years in the making but currently limited to lambs, is headed towards eventual human participants. Also currently limited to the lamb intensive care unit are the locally developed monitoring devices assessing novel biomarkers of fetal distress that may one day obviate the need for current CTG and fetal scalp lactate monitoring.6

Community benefits

Some technology is translating from other industries, such as the pasteurisation of breast milk, which has led to the establishment of non-profit breast milk banks benefiting preterm babies across Australasia.

- Canterbury, NZ: www.cdhb.health.nz/health-services/human-milkbank

- Victoria: Mercy Health Breastmilk Bank

- Queensland: Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Milk Bank

- Queensland and northern New South Wales: Mothers Milk Bank Charity

- NSW: Royal Prince Alfred Hospital

- Western Australia: PREM Milk Bank

- South Australia and New South Wales: The Australian Red Cross Lifeblood’s Milk Bank

The future

This leaves us to think, what else is possible? I imagine a 4D ultrasound scan that wraps around the pregnant pelvis in labour. It is able to precisely determine the anatomical landmarks of the fetal skull and maternal pelvis. It can tell cervical dilation, head position, and station. And when predetermined criteria are met, a robotic arm with a vast array of responsive sensors, made of a material yet to be discovered, attaches itself exactly on the vertex, distributing force to eliminate any trauma. With AI receptive learning, the arm then pulls with the perfect amount of traction in the necessary directions to allow optimal delivery. No longer the need for the Chambelens secret, and thereby the role of delivery room obstetrician becomes obsolete.

References

- Dunn PM. The Chamberlen family (1560–1728) and obstetric forceps. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 1999;81:F232-F234.

- Burke H. Who are the top 10 medical device companies in the world? Proclinical Blogs, 2020. Available from: www.proclinical.com/blogs/2020-9/who-are-the-top-10-medical-device-companies-in-the-world

- Burke H. Who are the top 10 medical device companies in the world? Proclinical Blogs, 2020. Available from: www.proclinical.com/blogs/2020-9/who-are-the-top-10-medical-device-companies-in-the-world

- Deloitte. Mobile Consumer Survey: The Australian Cut. 2017. Available from: www2.deloitte.com/au/mobile-consumer-survey

- De Bie FR, Davey MG, Larson AC, et al. Artificial placenta and womb technology: Past, current, and future challenges towards clinical translation. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2021;41:145–58.

- RANZCOG Virtual ASM 2021 – Fiona Brownfoot, Fetal Monitoring in Complex Pregnancies.

Leave a Reply