This O&G Magazine feature sees Dr Nisha Khot in conversation with RANZCOG members in a broad range of leadership positions. We hope you find this an interesting and inspiring read. Join the conversation on Twitter #CelebratingLeadership @RANZCOG @Nishaobgyn

Prof Ruth Stewart

DRANZCOG Adv

In this issue of O&G Magazine, I speak to Prof Ruth Stewart, Australia’s second National Rural Health Commissioner. She has been called Australia’s ‘First Lady’ of rural health. She is also a Diplomate of RANZCOG and worked as a GP obstetrician (GPO) in Camperdown in south-west Victoria for 22 years. Her PhD research examined the lessons learnt from a Managed Clinical Network of rural maternity services in south-west Victoria. Her experience of rural healthcare is not just professional; she herself was born prematurely in a bush nursing hospital in Victoria and, in turn, had three of her four children in a small rural hospital.

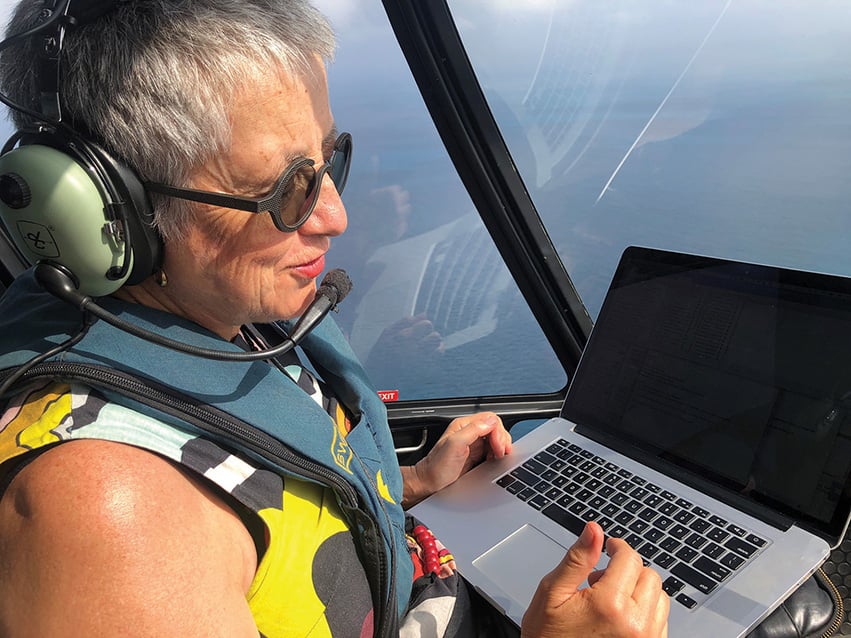

Prof Ruth Stewart in a chopper over Thursday Island.

Prof Stewart lives on Thursday Island in the Torres Strait. She had held many leadership positions including Director of Rural Clinical Training at James Cook University, Director of Medical Training with Queensland Rural Generalist Program (2014–16), and President of the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM) (2016–18). She has been a board member of the Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service, Rural Doctors Association of Australia, ACRRM and the Tropical Australian Academic Health Centre.

Incidentally, did you know that RANZCOG has approximately 1.5 times as many Diplomate members as Fellows? Our GPO colleagues far outnumber us specialists within the College. In recognition of their valuable contribution, Diplomates now have representation on the College Board. The College actively supports GPOs by providing refresher courses as well as co-ordinating the Advanced Diploma in obstetrics and gynaecology.

Why is it so important to keep rural maternity services open? If you missed it, I highly recommend this video entitled ‘Beating Hearts of Australia’ produced by RANZCOG that highlights how rural maternity services provide the beating heart of any community.

What does a typical day for Australia’s Rural Health Commissioner look like?

There isn’t really any typical day. I am travelling a lot so what I do depends really on where I am. I like to start my day with a bike ride wherever I am and even though I am travelling, I try to travel with a bike, usually a mountain bike, so I can go for a ride every day. The first thing I do after my ride is to connect with my team – my EA to discuss the agenda for the day, to check I have all the information and documents I need for the meetings scheduled for the day. After that, I connect with one or more of my senior advisors to talk through the schedule for the day. I have a team of five advisors, including two senior advisors and a principal advisor who manages external relationships. My day is usually very structured with meetings, most often these days they are video-conferenced, but with a gradual return to travel in Australia, I am now beginning to have face-to-face meetings. I have just had a week where I travelled around western NSW visiting five rural communities where the government is funding innovative models of care. I spent the following week in Canberra meeting with politicians and key stakeholder groups and the Department of Health. My job is all about connections and communication and being the connector between community groups, peak bodies, key stakeholders and feeding their concerns and views to the Ministers for Heath and the Department of Health.

What made you choose the rural pathway?

I always wanted to be a rural doctor; I went into medicine with this intention without understanding it to be unusual at the time. I grew up in a country town and I wanted to be like the doctors I knew during my early years. They were very much of the model that we would now call rural generalists. I didn’t particularly enjoy my medical course and, from time to time, I would think of all the other things I would rather be doing. Every time I said this, my mother would say to me, ‘Look, before you decide on leaving the course, how about you just spend a day or two with our local doctors. If you still think medicine is not what you want to do then you can drop out.’ Each time I would do this, it made me realise that this was really what I wanted to do. My problem was that the work of rural doctors was pretty much invisible at the University of Melbourne where I was doing my medical degree and I worked out pretty quickly that if I wanted to be a rural doctor, I didn’t need to impress anyone at the university because they didn’t actually care about that kind of work. I think things have changed significantly now or at least I hope they have. I hope that aspiring rural doctors feel valued during their undergraduate years these days. But this certainly was not the case in the early 80s.

What advice would you give to medical students or junior doctors who may be considering a rural pathway but are unsure partly because they have experienced the attitude you describe toward rural medicine?

I think if you want to make a real difference to the health of Australians then the opportunities to make a tangible difference are in rural and remote medicine and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. These groups have the least access to healthcare and the worst health outcomes. Sometimes people think that there isn’t a fulfilling career path in rural medicine, but my career demonstrates that there are lots of different things you can do in rural medicine. I have had a very active life as a clinician providing obstetric care. I have then moved to academia, done a PhD, been involved in medical politics and policy development and now in my current role, I spearhead future planning for rural healthcare development. I have had a very full life as a rural doctor and I have never gone to bed wondering if what I am doing makes a difference. I know it makes a difference.

Following on from this, how does a rural GPO find a pathway to academia and medical politics?

In the early 2000s, I had started to do a master’s degree with a research project and I was on the board of ACRRM. I was really interested in exploring what was required to train rural doctors of the future. Being on the Board, I learned a lot about the principles and theories of medical education. A rural medical school (Deakin University) was starting up in south-west Victoria. At the time, I was a GPO in Camperdown and I looked at the faculty and thought that there really wasn’t anyone on the faculty with knowledge or experience in rural medicine. So, I applied for one of the jobs and astounded myself more than anyone else by becoming the Associate Professor of General Practice/ Rural Medicine establishing the rural program for Deakin University. Along the way, I completed my PhD. In 2012, I moved to North Queensland to become the Director of Rural Clinical Training at James Cook University where I oversaw the doubling of rural clinical placements for the medical school. I continued to be on the Board of ACRRM and went on to become President. The pathways exist, one just has to find them. And where they don’t exist, one has to make them and hope that others will follow.

How does Thursday Island fit into all of this?

My husband and I moved to North Queensland when I started at James Cook University and I said to my husband that he could choose where we lived just so long as it was in the JCU patch, and he chose Mareba, which is a town up on the Tablelands from Cairns. He started off as Senior Medical Officer in Mareba. He had a lot of governance and management experience from his previous roles in Victoria. He went on very quickly to take on leadership roles within the Cairns and Hinterland Rural Health Service. The position of Director of Medical Services at Torres Strait Health Service came up and I encouraged him to apply for that role because he is a change agent and I could see that he would be the person who would be able to lead the changes required in the service. He took up the position and that is when we moved to Thursday Island. He subsequently became the Executive Director of Medical Services for Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service. Initially when we moved up there, we were both doing some clinical work but as our other roles became more senior, we both stopped our clinical work. So home is on Thursday Island, which is one of the smaller Torres Strait islands. Getting there involves flying from Cairns to Horn Island followed by a ferry to Thursday Island. You can also drive up Cape York but that is a much longer, arduous four-wheel-drive trip. I wouldn’t recommend it more than once.

How do you balance your personal and professional life?

When I agreed to take on the role of National Rural Health Commissioner, my husband and I decided that we would prioritise spending time together. That meant that when the pandemic started, we decided that if travel was necessary, we would travel together so we wouldn’t get stuck, apart from each other with state border closures. Both of us share a love of cycling. We prioritise staying connected to family and friends who are now scattered across Australia.

What do you see as the challenges for rural maternity care in Australia?

The biggest challenge is keeping rural maternity services open. In the last 30 years, 70% of rural birthing services have closed. The decision is often economic, but this means that rural women have to bear the cost of travel to access maternity care. We know that rural communities tend to be economically deprived, and this additional burden of cost is unfair. The decision making has often not been woman-centred. Safety statistics are quoted as another reason for closing birthing services. In my research, I found over 40 clinical audits of safety of rural maternity services and only two of them suggested that rural maternity services are less safe than urban services. When we looked at these two studies, there was ample evidence that they are flawed. It is important that we dispel this misconception that rural birthing units are unsafe. The quality of rural services is good but what is lacking is support from the system to maintain and continually improve the care rural women receive in pregnancy and during childbirth. The problem is that reopening a closed service takes much more time, money and effort. We have had some success stories with reopening closed units, but these are few and far between.

What would you tell your younger self if you had the chance to go back in time?

I would tell myself that being different can be an advantage. I was that medical student who got into medicine with an advantage in literature and communication. It used to worry me that there were others who remembered all the details of chemical bonds and cycles that I had difficulty managing. But in fact, being just adequate in the pure sciences but an excellent communicator has made me a better doctor and a more effective health activist. When it comes down to it, being a doctor is standing in the gap between the patient and the science and translating the science into simple terms to help patients make choices that are right for them. And doing this requires an understanding of science but more than this, it requires language and communication skills.

Do you have advice for aspiring women leaders?

You can do it and you should. I observed very early on in a clinical teaching session when the tutor asked us to do something, the men in the group immediately put their hands up while the women didn’t. I thought to myself at the time, ‘I know who the competent clinicians in this group are. Why have the competent women not stepped forward?’

It is not that men don’t do a good job. It is that women want to be better than good before we will consider taking on a role. We need to recognise that sometimes you can do a job better if you are not perfect. And embrace learning on the job.

What does the future hold for you?

My current role is a political appointment and I feel a great sense of urgency to get things done. Things such as the national rural generalist program, increasing access for rural and remote communities to allied health services and reforms to primary care in Australia to improve access to healthcare for rural Australians. I didn’t graduate with the goal of leading rural healthcare. I graduated wanting to become a good rural doctor and I was one for many years. There were occasions when I would get frustrated and look around and think, ‘Why don’t they…? Why doesn’t someone…?’. Until I realised that there was no knight in shining armour coming to save rural health. It has got to be people like you and I who step up and take responsibility to be leaders. To be honest, this was a fairly challenging decision for me. I grew up under the strong influence of the tall poppy syndrome, so I had to overcome the sense of wanting to just fade into the background. It was in my early 40s that I thought that fading into the background doesn’t seem to work for me. Even when I was standing in the background, people were looking to me either thinking that I should lead or getting cross with me because they felt I was undermining their leadership when I had no intention of doing this. I had to accept that I was a leader and focus on how to do it well. Its not that I can do things better, but I try hard to listen and reflect and communicate well. This has made all the difference in the way I have approached all my leadership roles.

Are you optimistic about the future of remote and rural healthcare?

Yes, I am optimistic, and it is the medical students, interns and junior trainees that make me optimistic. There are many more students who are not just interested but passionate about rural healthcare. It is now our responsibility to set up the systems that facilitate their career pathway into generalist rural training pathways. When we give students the opportunity to study and train in rural communities, they enjoy their experience, they can see the purpose and the difference they can make. At the moment, the paths to rural and remote practice look a bit like a Snakes and Ladders board and we need to make a clear pathway instead. My aim is to help redesign the system to make the path clear and easy to access for anyone who wants to be a rural doctor.

You can follow Prof Ruth Stewart on Twitter @raatusruth.

Leave a Reply