The idea of uterine transplantation has been around since the 1960s. Animal studies conducted in Sweden, UK and the USA demonstrated it was possible to transplant the uterus resulting in successful pregnancies in multiple animal models.

The first uterine transplant was performed in Saudi Arabia in 20001 and the first live birth following uterine transplantation took place in Sweden in 2014.

Since then, many more transplants have been performed around the world with the details of 45 reported in 2019.1 By late 2020, more than 70 uterine transplants had taken place with 23 live births, mostly from live donors. There has been evolution of the surgical technique using same arterial input but use of ovarian veins for drainage and reduction in operating time.

Uterine transplantation is for uterine factor infertility, which is defined as the lack of a functional uterus. This can be congenital or acquired. The vast majority of cases performed were for women with Mayer-Rokitanski-Kuster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH). MRKH occurs secondary to the incomplete development of the Müllarian duct. In type 1, the upper vaginal and uterus are under developed and in type 2 other organs such as fallopian tubes, kidneys and spine are also affected. The only options for women with MRKH to reproduce have been surrogacy or adoption. In many countries throughout the world, surrogacy is illegal and therefore not an option for women. The most common acquired indication in the women undergoing transplantation is hysterectomy for reasons such as cancer and haemorrhage and indications have included Asherman’s syndrome.

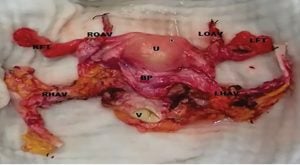

Figure 1. Photograph of surgical specimen prior

to transplantation, courtesy of S Saso, Imperial College, London.

There are ethical, medical and resource issues to consider with regards to uterine transplantation. Most organ transplants are life preserving procedures and the most experience and information is with renal transplantation. Uterine transplantation is life enhancing rather than life preserving, giving women who otherwise would not be able to have children the option of childbirth. Obstetricians have seen many successful pregnancies following renal transplantation of women taking immunosuppressive medication. Immunosuppressive medication such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine have been used in pregnancy for some time and are also used to prevent rejection of the uterine transplant.

Donation has taken place after brainstem death and the first live birth following this was in Brazil in 2017. There are advantages of live donation in reducing risk of ischaemic injury; however, the risks to donor are an important consideration. Risks to the donor and recipient need to be assessed and minimised. As this is a relatively new procedure, the risks and complications have been outlined in case series and include graft failure due to thrombosis, graft rejection, ureteric injury, vesicovaginal fistula and vaginal cuff dehiscence as well as pulmonary embolism secondary to long operating time. Pregnancy complications include preterm birth and low birth weight. Units performing transplants have established guidelines for assessment of both donors and recipients and have developed exclusion criteria. Delivery is by caesarean section and subsequent hysterectomy is performed so that immunosuppressive therapy can be discontinued.

Support for this procedure is variable amongst practitioners and the wider community. Ethical considerations are important with the need for appropriate counselling and support. The surgery is complex and requires a multidisciplinary team. Women seeking pregnancy are a vulnerable group and may underestimate their risks. Surgical techniques have improved, and operating times halved since the early cases. Women who do not have access to adoption or surrogacy may seek this option if it is available.

Further reading

- Fageeh W, Raffa H, Jabbad H, Marzouki A. Transplantation of the human uterus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;76(3):245-51.

- BP jones, S Saso, et al. Human uterine transplantation: a review of outcomes of the first 45 cases. BJOG. 2019;126(11):1310-9

- Ricci S, Bennett C. Uterine Transplantation: evolving data and clinical importance. J Minim Invasive Gynaecol. 2020;S1553-4650(20)31188-2.

- Brannstrom M, Johannesson L, et al. Livebirth after Uterus transplantation. Lancet. 2015;385:607-16.

- Brännström M, Wranning CA, Altchek A. Experimental uterus transplantation. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(3):329-45.

Leave a Reply