Case Description

A 38-year-old woman, G4P3, presented at 36+1 with intermittent upper abdominal pain and heartburn. She denied any vomiting, changes in bowel habit or recent abdominal trauma. She had recently completed a course of oral antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Her past obstetric history included two vaginal births followed by a caesarean section for placenta praevia. She was planning a vaginal birth in this pregnancy. She also had an elevated BMI of 40, chronic hypertension, previous renal stones and laparoscopic gastric sleeve since the birth of her youngest child.

On admission, she had normal vital signs and a soft abdomen. Cardiorespiratory examinations were not performed at the time. Her full blood count, liver function tests and urine dipstick were all normal. She was started on regular omeprazole and buscopan for presumed gastric reflux with initial improvement, therefore she self-discharged prior to imaging.

The following day she re-presented with a recurrence of severe pain, localising to the left flank. She had a renal tract ultrasound, which excluded obstructing renal stones. Despite now requiring IV morphine for her pain, she was haemodynamically stable and her abdomen remained soft. However, she was found to have absence of breath sounds in the left lung field on chest auscultation.

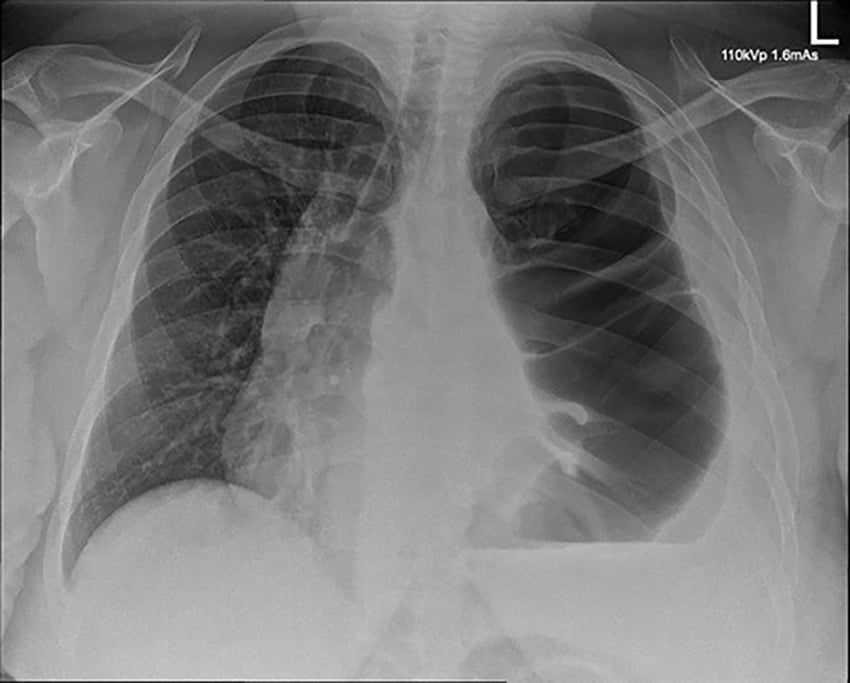

Repeat blood tests showed a CRP rise from 3 to 104. Chest X-ray (CXR) showed a bowel herniation into the left hemithorax with mediastinal shift to the right (Figure 1). CT chest and abdomen confirmed a complete collapse of the left lung due to the large, left posteromedial diaphragmatic hernia with intrathoracic transverse colon.

Given the severity of pain and increasing respiratory distress, the joint decision between obstetrics and general surgical teams was to proceed for combined caesarean section and subsequent reduction and assessment of the diaphragmatic hernia (DH). An uncomplicated caesarean section was performed under combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia via pfannestiel incision and baby was delivered in good condition.

Following closure of the uterotomy, the general surgeons identified a 2cm DH. They attempted to reduce the herniated bowel with gentle traction; however, this was limited secondary to patient discomfort. Therefore, the surgery was converted to general anaesthesia and additional midline vertical incision was made to reduce the herniated contents.

Following reduction, the transverse colon was noted to be distended with multiple serosal tears. Therefore, an extended right hemicolectomy was performed given the unhealthy appearing bowel concerning for ischemia.

Histological findings were consistent with early ischemic changes with areas of serositis and mural fibrosis. At the end of surgery, the anaesthetist placed a chest drain in the left chest as there was a breach in the parietal pleura causing hydropneumothorax.

The mother required extended hospital admission following her surgery. However, she made a good recovery with rapid improvement to her cardiorespiratory symptoms.

Figure 1. CXR demonstrating bowel loops with haustral folds herniating into the left hemithorax with marked mediastinal shift to the right.

Discussion

DH in pregnancy are rare, with less than 50 cases reported in literature between 1959 and 2016.1 Early diagnosis and management are critical to avoid life-threatening complications including respiratory failure and bowel obstruction.

The majority of DH are mostly congenital, affecting 1 in 3000 births.2 They are usually diagnosed antenatally and repaired in the neonatal period. Acquired DH result from increased intra-abdominal pressure, most commonly due to penetrating and blunt abdominal trauma which compromises diaphragmatic integrity and allows abdominal organs to enter the chest cavity. Diaphragmatic defects occur more frequently on the left than the right. This is attributable to the protection provided by the liver.

In this case report, we describe a rare case of acquired maternal diaphragmatic hernia manifesting late in pregnancy. The patient’s previous gastric sleeve operation was thought to prevent herniation of the stomach through the hernia. It is likely the hernia manifested on a basis of pre-existing anatomical weakness, exacerbated by increased intra-abdominal pressure in pregnancy.

Adults with DH can present with a variety of symptoms relating to abdominal viscera herniating into the pleural cavity. Symptoms can include chest pain, shortness of breath, heartburn, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and the inability to pass flatus or stool. These are often non-specific and are commonly reported complaints during pregnancy, making diagnosis challenging. Therefore, it is important to perform generalised review of systems in all those presenting with an unclear diagnosis. On physical examination, reduced breath sounds on the ipsilateral side is the most common finding for DH.3 Failure to respond to antacids, antispasmodics and dietary changes should also raise the suspicion of underlying bowel pathology.

Imaging modalities useful in evaluating DH include CXR, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT is considered the gold standard, as it can both localise the exact defect while also demonstrating the extent of herniated organs involved. CXR has a sensitivity of 70% as pleural effusion and pneumothorax often mimic the findings seen with DH.4 MRI may be appropriate when patients are haemodynamically stable and have relative contraindications to CT such as contrast allergies or pregnancy. In this case, a CT scan was performed given the worsening symptoms and cardiorespiratory involvement. It also allowed assessment of the bowel.

Surgical management of DH is advised as the diaphragm is in a constant state of movement during respiration. Therefore, a diaphragmatic defect rarely heals without intervention.5 Timing of surgery for pregnant women depends on the severity of symptoms and the gestational age. Symptomatic women with investigations demonstrating bowel compromise or cardiorespiratory involvement should proceed with emergent DH repair without consideration of gestational age. In asymptomatic women, elective surgery can be planned for the late first or second trimester. In third trimester, DH repair should take place simultaneously with caesarean section to avoid anaesthesia-related complications.6 Between 24–34 gestational weeks, it is possible to consider steroid treatment and nasogastric decompression until the patient can be transferred to a tertiary hospital and surgery can be planned.

With regards to the mode of delivery, we recommended caesarean section for our woman due to the increased risk of cardiorespiratory compromise during labour with known mediastinal shift and left lung collapse. Kurzel and Naunheim6 studied 17 case reports of women with DH in pregnancy, and they advised against vaginal delivery under any circumstance due to the risk of bowel strangulation when the woman is bearing down.

Conclusion

Diagnosing DH in pregnancy is challenging given the non-specific symptoms which mimic normal pregnancy, resulting in delays in treatment. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required when reviewing women with recurrent non-specific symptoms as DH is associated with high maternal and fetal mortality rates.

References

- YS Koca, I Barut, I Yildiz, et al. The cause of unexpected acute abdomen and intra-abdominal hemorrhage in 24-week pregnant woman: Bochdalek hernia. Case Rep Surg 2016;6591714.

- Chandrasekharan PK, Rawat M, Madappa R et al. Congenital Diaphragmatic hernia – a review. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017;3(6).

- Panda A, Kumar A, Gamanagatti S et al. Traumatic diaphragmatic injury: a review of CT signs and the difference between blunt and penetrating injury. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2014;20(2):121-8

- Gimovsky ML, Schifrin BS. Incarcerated foramen of Bochdalek hernia during pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1983;28:156-58.

- Katukuri GR, Madireddi J, Agarwal S et al. Delayed Diagnosis of Left-Sided Diaphragmatic Hernia in an Elderly Adult with no History of Trauma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(4):4-5.

- RB Kurzel, KS Naunheim, RA Schwartz. Repair of symptomatic diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:869-71.

Leave a Reply