Ensuring a positive experience and providing respectful woman-centred care is a fundamental expectation of maternity services in Australia, New Zealand and globally. The pathway to getting to this goal may differ for each woman, so maternity services need to be adaptable and supportive of the woman’s context.

During the COVID-19 lockdown many countries reported increased interest from women about homebirth and/or freebirth. Freebirth refers to a woman’s intention to give birth at home without the assistance of a health professional. The increased interest in giving birth in out-of-hospital settings was for several reasons:

- Hospitals were considered a locus of infection

- Hospital policies significantly restricted or inhibited visitors or support people

- Women wanted more support people with them when giving birth

Some women considered freebirth because of the unavailability of health professional support for a homebirth. In a recently published paper exploring women’s motivation for freebirth (undertaken prior to COVID-19) women identified a desire for autonomy, a previous negative hospital experience and concerns about interruptions and unnecessary interventions during labour and birth as reasons to consider freebirth.1 However, the desire for autonomy and a positive birth experience is not limited to women choosing out-of-hospital birth settings. Women come from diverse backgrounds and have different needs, expectations and challenges but all want the same thing from maternity care – a healthy baby and a positive childbirth experience.

In maternity hospital settings where a woman may meet a number of different health providers, often for the first time when in labour, how do we ensure that her expectations are met and she has a positive experience?

Organisation of maternity care

Adaptable woman-centred care requires the provision of information and informed decision making in all areas of maternity care. Each woman should be able to choose her care provider, the place of birth and the care that best suits her needs and expectations. In New Zealand, women can choose a midwife, obstetrician or general practitioner to provide her care as her Lead Maternity Carer (LMC), with the majority choosing a midwife (94.1%) and receiving continuity of care through pregnancy, labour and birth and up to six weeks following the birth.2 Continuity of care benefits women and babies3 and the midwives providing that care.4 Women who have medical, obstetric or neonatal concerns are referred to the secondary maternity team within the hospital but will often also have a midwife LMC, who works collaboratively with the team. The LMC midwife provides elements of the woman’s care in the community and often intrapartum care in the hospital.

Maternity care provider

Finding the right midwife for the woman is important for both the woman and the midwife. The College of Midwives provides a website that supports women to find a midwife nationally (www.findyourmidwife.co.nz) in her town/city/area. The website identifies the midwives who are available at the time of the woman’s due date, their philosophy of care, their practice colleagues, and the maternity units they access when providing care (includes homebirth, primary units and secondary/tertiary maternity hospitals within the region).

Options for place of birth

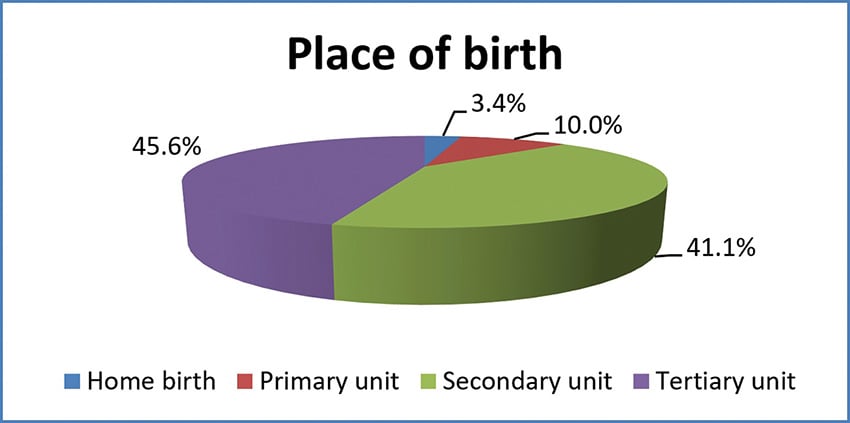

New Zealand women have options of homebirth, midwifery-led unit birth, secondary/tertiary maternity unit birth (Figure 1). In addition, there are formal structures for referral and shared care for those women who need obstetric, physician, anaesthetic or neonatal expertise.

Figure 1. Place of labour and birth in New Zealand in 2017.

Referral for obstetric consultation

The Guidelines for Consultation with Obstetric and Related Medical Services (Referral Guidelines) are used as the basis to support referrals and support consistency of consultation, transfer and co-ordination of care across providers.5 Skinner6 found that 35% of women were referred to obstetric services for a variety of reasons but that following referral, most midwives continued to provide midwifery care in collaboration with specialist services.

Information sharing and informed choice

During pregnancy, the midwife provides education, information, health promotion, health assessment, screening and care planning. She gets to know the woman and starts to build a partnership based on mutual trust, respect and understanding.

Working with the woman, the midwife develops a birth plan that sets out her individual needs and expectations for labour and birth. Informing women and supporting an informed decision is a consumer right within New Zealand and is reflected in the systems and organisation of maternity care.7 Birth plans are adaptable and midwives will discuss the potential for additional or different care dependent on the context and the woman’s labour and birth process.

Working as a team to support woman-centred care

Woman-centred maternity care requires that maternity health professionals work together to put the woman at the centre of maternity care and ensure that her needs are met in a connected, cohesive and responsive way. In New Zealand, integrated care refers to the primary-secondary interface which requires referrals from primary care (community midwives) to secondary care (obstetric team) and back again following birth.

Woman-centred care in action

I met Jennifer when she was eight weeks pregnant with her third baby. We discussed her previous two births, both had been induced – for different reasons – her first baby had been an assisted birth and the second a normal birth. She didn’t want to be induced again and was hoping for a spontaneous labour this time. Her pregnancy progressed and at almost 42 weeks, she had no signs of labour but was adamant that she did not want to be induced again. We discussed the increased risk of stillbirth if pregnancy passed 42 weeks and explored her reasons for not wanting to be induced. She explained that with her two previous inductions, her body had responded rapidly to the syntocinon and she had started to feel out of control. She felt that the contractions went from zero to ‘full on’ in a very short time. She asked if it was possible to stop or slow the syntocinon once the induction was commenced. We agreed to discuss this idea with an obstetrician. Following a referral and admission to the birthing suite, we met the on-call obstetrician and, with Jennifer’s agreement, I explained her concerns and potential solution. Together we explored the potential benefits and risks – and agreed that we would stop the syntocinon once the labour was established, with the proviso that we would need to start it again if labour stalled.

We commenced the induction and Jennifer started to contract frequently, at which point we stopped the syntocinon. She continued to labour and within hours had given birth to a healthy baby. I debriefed with Jennifer a few days later, with careful questions about how she felt about having an induction. She told me she was very happy with her experience and decision to go ahead with the induction, that she had been listened to and her birth plan had been honoured. Overall it had been a positive experience.

Interprofessional relationships

Providing an integrated response can be difficult to achieve when there are different health professionals with different expertise, expectations and philosophies working together. One qualitative exploratory study set in four rural communities in Canada8 found that barriers to integrated and collaborative care were often related to the organisation of care and interprofessional tensions between health professionals. These included negative perceptions of midwifery and homebirth and confusion about roles and responsibilities.

The core principles that support the building of professional relationships are collaboration, communication, co-operation and the building of trust and respect.

Collaboration

Collaboration can be defined as the ‘process of two or more people working together to achieve a goal’. RANZCOG9 identify that collaboration is important to support improved outcomes for women and their babies and maternity services should actively promote participation of different health disciplines so that the individual woman’s needs are met. The NZ Referral Guidelines set out the guiding principles for health professionals to ensure clarity and consistency and improve collaboration.

Communication

Effective communication is vital to ensure the exchange of context-appropriate information from one health professional to another. Most LMC midwives in New Zealand will continue to provide care during labour and birth – although some will hand over care to hospital midwives. Good communication is not always intuitive and there are a number of tools that support effective communication. One commonly used in hospitals is the ISBAR – introduction, situation, background, assessment and response. Including the woman and her care plans and expectations during the referral is important to ensuring fully informed decision making.

Co-operation and teamwork

Working together to ensure that the woman’s needs are met is paramount in any collaboration. In maternity it requires midwives and obstetricians to work together as a team to ensure that the woman’s needs are met whilst supporting a safe birth for her and her baby. Team members may include the obstetrician, hospital and community midwife, anaesthetist and paediatrician. Each team member brings their own expertise along with a shared goal and common understanding. Principles involve mutual respect and trust for each professional’s perspective and outlook.

Conclusion

Integrated care works best when there are clear guidelines and referral structures and positive and supportive interprofessional relationships. In New Zealand, community midwives provide continuity of maternity care (getting to know the woman and her maternity history), and the maternity system is organised to support referral and transfer of care (when needed) along with an integrated response and respectful care from the hospital team.

References

- Jackson MK, Schmied V, Dahlen HG. Birthing outside the system: the motivation behind the choice to freebirth or have a homebirth with risk factors in Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):254.

- Ministry of Health. Report on Maternity 2017. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2019.

- Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, et al. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD004667.

- Dixon L, Guilliland K, Pallant J, et al. The emotional wellbeing of New Zealand midwives: Comparing responses for midwives in caseloading and shift work settings. New Zealand College of Midwives Journal. 2017;53:5-14.

- Ministry of Health. Guidelines for Consultation with Obstetric and Related Medical Services (Referral Guidelines). Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2012.

- Skinner J. Being with women at risk: the referral and consultatin practices and attitudes of New Zealand midwives. New Zealand College of Midwives Journal. 2011;45:17-20.

- Health and Disability Commissioner. Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights. 1996. Available from: www.hdc.org.nz/your-rights/the-code-and-your-rights

- Munro S, Kornelsen J, Grzybowski S. Models of maternity care in rural environments: barriers and attributes of interprofessional collaboration with midwives. Midwifery. 2013;29(6):646-52.

- RANZCOG. Maternity Care in Australia. Australia: RANZCOG; 2017.

Leave a Reply