It is well documented that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter, respectfully, First Nations) people bear an excessive burden of disease, disability and mortality across the lifespan. This starts in the early years and, despite national initiatives such as ‘Closing the Gap’, for the past 12 years (since targets were set in 2008) there has been little or no improvement in key maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) indicators when comparing First Nations mothers and babies to other Australian women.1 Maternal death remains 3–5 times higher,2 perinatal deaths 1.7 times higher with preterm birth almost double; and unchanged in 12 years.3 Preterm birth is the largest contributor to child mortality4 and is associated with significant childhood disability5 and chronic diseases in adulthood.6

Although many First Nations families live in urban areas, a little-known fact is that approximately 71% of First Nations birthing mothers live in rural, remote and regional areas, compared to only 27% of non-Indigenous women. Our maternity services do not reach into many of these areas and we see the inverse care law in action – where those who have the highest burden of disadvantage have the poorest access to services.

In the last few months, we have seen the Australian healthcare system adjust and seek innovations to respond to the novel coronavirus by implementing significant changes (such as transition to telehealth) in record time. We could do the same to improve health for First Nations women, babies and families, by taking urgent practical action to support improved access to care. Birthing on Country services provide trialled and tested solutions to fast track significant service redesign in partnership with First Nations communities for maximum health gains.7 This service model resulted in a 50% reduction in preterm birth in South East Queensland. Birthing on Country services are recommended in the national Strategic Directions for Australian Maternity Services8 and the National guidance for implementing Birthing on Country Services has been endorsed by state and Commonwealth governments.9 Australia’s response to this pandemic has proved that we are capable of rapid strategic action to safeguard our health: it’s time we extend this action to First Nations families to achieve health equity in maternal and infant health.

Birthing on Country services: best start to life

First Nations women across Australia have led the drive to have Birthing on Country for decades. The aspirations and urgency of Birthing on Country becoming a reality is best captured in the following:

‘[Birthing on Country should] be understood as a metaphor . . . for the best start in life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies and their families because it provides an integrated, holistic and culturally appropriate model of care; ‘not only bio-physical outcomes . . . it’s much, much broader than just the labour and delivery . . . . (it) deals with socio-cultural and spiritual risk that is not dealt with in the current systems.

Birthing is the most powerful thing that happens to a mother and child . . . our generation needs to know the route and identity of where they came from; to ensure pride, passion, dignity and leadership to carry us through to the future; [Birthing on Country] connects Indigenous Australians to the land.’ Djapirri Mununggirriti at the National Birthing on Country Workshop 2012.10

Birthing on Country services consist of significant service redesign, increased First Nations control of service planning and delivery, increased employment of First Nations people, and continuity of midwifery carer delivered within an integrated system linking primary and tertiary services. The key elements of the Birthing on Country services are described in Box 1.

- First Nations governance of the service.

- Improved integration between tertiary and Aboriginal community-controlled sector.

- Continuity of midwifery carer 24/7 during pregnancy, birth and up to six weeks postnatal.

- Strategy for increasing and capacity building the First Nations workforce: Family Support Workers, student midwifery cadets, new graduate midwifery positions, transport workers, senior management, administration, social worker, psychologist, practice nurse and program manager.

- Cultural and clinical supervision for frontline staff.

- Community-based hub with access to resident or outreach specialised paediatric and women’s health services and social and emotional wellbeing team.

- Cultural strengthening and revival programs: culture and connection days, arts program.

- Intensive support for women and families: strong focus on family preservation (keeping families together) and restoration (returning children to parents).

- First Nations Controlled Birth Centres (i.e. choice of birthplace).

Birthing on Country services have a profound impact on outcomes

The Birthing on Country service in Brisbane (Meanjin), on the traditional lands of the Turbal and Jagera Nations, reported maternal and infant outcomes that have not been witnessed in Australia for the past decade.1 The service is called Birthing in Our Community. The improvements are across numerous categories including First Nations workforce, integrated and wrap-around services that are women and baby centred, early community engagement and clinical outcomes (Box 2). They resulted from a partnership between two Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health Organisations and a tertiary hospital: the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service Brisbane and the Mater Mothers’ Hospital. The partners worked together to redesign and deliver services from 2012.11

| Box 2. Birthing in Our Community outcomes | |

Increases in:

|

Reduction in:

|

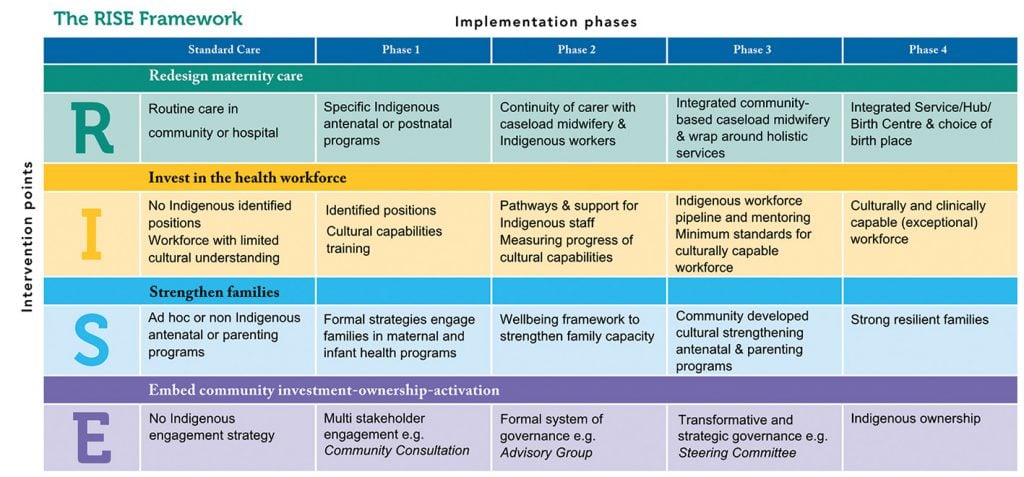

The RISE Framework for implementing Birthing on Country

Birthing on Country is a complex intervention that incorporates a redesigned maternal and infant health service for greater quality and safety. It operates within a First Nations governance framework and addresses the determinants of living by rapidly increasing the First Nations workforce and providing comprehensive integrated services to support family’s capacities and opportunities.

The RISE Framework is informed by First Nations relationality (interconnectedness) of people, animals, plants, place, time and ceremony. The intersections and synergy that bring First Nations knowledge to the forefront is critical in understanding First Nations aspirations for maternal and infant services and, importantly, how to inform the design of clinically and culturally safe services.12

The RISE Framework for implementation includes:

- Redesign the health system and services

- Invest in the maternal and infant health workforce to grow the First Nations workforce and ensure the non-Indigneous workforce is culturally safe

- Strengthen family capacity

- Embed community engagement, governance and control over health and research services

The RISE Framework has been informed by learnings from over a decade of research on maternity case studies for First Nations women, babies and families.

The RISE Framework can be locally adapted to the diverse needs of each First Nation community, while also assessing and utilising the available resources such as the workforce, infrastructure etc. However, there are key areas that if implemented immediately could make a profound difference in maternal and infant outcomes for First Nation mothers, babies and families; these are:

- Additional funding to Aboriginal Community Controlled Health organisations to employ midwives to work in continuity of care services and embed and monitor cultural safety

- Immediately implement the recommendations in the Report of the Review of Medicare for Midwives13 to enable Aboriginal Community Controlled Health organisations to utilise Medicare funding for midwifery services – recommendations were supported by the whole panel included doctors / obstetricians.

Figure 1. RISE framework of First Nations maternity care

COVID-19 provides an example of how things can change rapidly when politicians, health services and the wider community are motivated to unite against a common threat. Concurrently, there has been an international groundswell to support the Black Lives Matter movement. We have demonstrated dramatic improvements in ‘black’ birthing outcomes. With widespread medical, obstetric and government support, we could all get behind the Birthing on Country movement and show that black babies’ lives mater too.

Policy makers and healthcare institutions can feel overwhelmed and be slow to act; however, the list below provides things that you can do to help the Birthing on Country movement:

- If you’re not sure how to respond, listen. If you’re not sure what to read, research. If you’re not sure what to do, donate. ‘Not sure’ becomes ‘not my problem’ it’s not enough to be ‘not sure’ when First Nations women and babies are dying prematurely, especially when we have the evidence that makes a difference.

- Reach out to your local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health Service – ask how can you work together, for example: increase the provision of outreach services, explore or support a partnership with the service you work in: let them lead. www.naccho.org.au

- Support the changes that are recommended in the review of Medicare for Midwives so that Aboriginal community-controlled health organisations can employ midwives to provide care for their families.

- Call out racism whenever you see it: silent bystanders allow this unacceptable behaviour to continue.14 Learn how to be a good accomplice to First Nations peoples.15

- Amplify First Nations voices whenever you have the chance. If you don’t have the chance in your everyday, create one, such as a panel discussion at your workplace ensuring proper renumeration for speakers. Remember to follow up on feedback and recommendations generated from these discussions in a timely manner.

- Ensure you and the staff at the hospital you work at have participated in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific cultural safety training, including content on history, colonisation, racism, white privilege, cultural beliefs and protocols; as recommended by Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency, Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives (CATSINaM), Australia Indigenous Doctors Association and Australian Medical Association.

- Ensure your organisation and staff are up to date in implementing recommendations from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework , the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Curriculum Framework, the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards user guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and your state and territories’ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific policies and implementation plans (eg. Queensland Health Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Capabilities Framework).

- Donate to Waminda South Coast Birthing on Country GoFundMe project.

References

- Australian Government. Closing the Gap Report 2020. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; 2020. Available from: https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/content/closing-gap-2020

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Maternal deaths in Australia 2016. Canberra: AIHW; 2018. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/558ae883-a888-406a-b48f-71f562db3918/aihw-per-99-printable-PDF-of-web-report.pdf.aspx

- Australian Government. Closing the Gap Report 2019. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; 2018. Available from: www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/reports/closing-the-gap-2019/index.html

- Australian Government. Closing the Gap Report 2019. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; 2018. Available from: www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/reports/closing-the-gap-2019/index.html

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Maternal deaths in Australia 2016. Canberra: AIHW; 2018. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/558ae883-a888-406a-b48f-71f562db3918/aihw-per-99-printable-PDF-of-web-report.pdf.aspx

- Australian Government. Closing the Gap Report 2019. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; 2018. Available from: www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/reports/closing-the-gap-2019/index.html

- Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, et al. Reducing preterm birth amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies: A prospective cohort study, Brisbane, Australia. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;12:43-51.

- COAG Health Council. Woman-centred care: Strategic directions for Australian maternity services. Canberra: COAG Health Council as represented by the Department of Health; 2019. Available from: www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2019/11/woman-centred-care-strategic-directions-for-australian-maternity-services.pdf

- Kildea S, Lockey R, Roberts J, Magick-Dennis F. Guiding Principles for Developing a Birthing on Country Service Model and Evaluation Framework, Phase 1. Brisbane: Mater Medical Research Unit and the University of Queensland on behalf of the Maternity Services Inter-Jurisdictional Committee for the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council; 2016.

- Kildea S, Magic-Dennis F, Stapleton H. Birthing on Country Workshop Report, Alice Springs, 4th July. Brisbane: Australian Catholic University and Mater Medical Researh Institute on behalf of the Maternity Services Inter-Jurisdictional Committee for the Australian Health Minister’s Advisory Council; 2013.

- Kildea S, Hickey S, Nelson C, et al. Birthing on Country (in Our Community): a case study of engaging stakeholders and developing a best-practice Indigenous maternity service in an urban setting. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(2):230-8.

- Taskforce MBSR. Report from the Participating Midwife Reference Group. Canberra Australian Government Department of Health and Aging; 2018.

- Taskforce MBSR. Report from the Participating Midwife Reference Group. Canberra Australian Government Department of Health and Aging; 2018.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Racism stops with me. Available from: https://itstopswithme.humanrights.gov.au.

- Indigenous Action Media. Accomplices not allies: An Indigenous perspective and provocation. Version 2; 2014.

Leave a Reply