Management of an obstetric emergency is the routine responsibility of everyone involved in maternity care, from junior doctors to specialist obstetricians, midwives and anaesthetists. All staff involved in care of birthing women should be educated in emergency management and, given the incidence of many obstetric emergencies, periodic training and drills should also be undertaken.1

The fundamentals of early recognition and management can be applied to any obstetric emergency, remembering first to stay calm and call for help. Systematic assessment of danger, airway, breathing, circulation (and haemorrhage control), disability and immediate correction at each step is key. The fetus may be vulnerable to maternal hypotension and hypoxia, requiring attention to both patients. Assessing for danger to the patient and staff is easy to overlook, but at the forefront of our minds amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, alerting us to consider personal protective equipment prior to entering the emergent situation.

The role of the team leader during an obstetric emergency is multi-dimensional, requiring strong communication, decision making and management skills. This clinician could be from any discipline or seniority level. Observing a team leader effectively manage an obstetric emergency is empowering and inspiring. Calm and clear in their direction, they bring a sense of control to the situation with a confident presence tangible to colleagues and patients. With this situational awareness, they simultaneously assess the patient, escalate care and provide treatment or delegate tasks while communicating with the woman and her support person. They must guard against ‘tunnel vision’ or task fixation, and have rapport with the clinical team, the birthing woman and her support person, allowing concerns or ideas to be aired, further contributing to an overall coordinating or ‘helicopter view’ and optimising outcomes.2

Being the only clinician in the hospital to provide first responder management is an everyday reality for our widely dispersed rural and regional healthcare workers. With obstetricians, anaesthetists and theatre teams remotely on call, the threshold to identify an emergency or call for help may need to be lower to consider local resources – sometimes, this can require creativity and role-shifting! In city hospitals, those we call to help may be unavailable and sometimes it can feel just as lonely.

In a complete review of obstetric emergencies, it would be prudent to consider management of internal podalic version and breech extraction, obstetric haemorrhage, neonatal resuscitation, maternal collapse and perimortem caesarean section, amniotic fluid embolism, management of the obstetric trauma patient, eclampsia and epidural or spinal anaesthetic complications. Many of these topics deserve their own focused attention, so we focus here on ‘snack-sized’ refreshers of less common, specifically obstetric, emergencies with a procedural element.

Shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia is often an unpredictable and unpreventable obstetric emergency with an incidence of between 0.58% and 0.70%.3 The anterior shoulder becomes impacted behind the symphysis pubis during vaginal birth, delaying delivery of the body after the head is born and requiring additional manoeuvres beyond routine axial traction.4 Warning signs may include slow progress and crowning or ‘turtling’ of the head. Neonatal consequences can include Erb’s Palsy, fractures and hypoxic injury, with fetal pH falling by between 0.0115 and 0.046 per minute after delivery of the head. Maternal morbidity is often related to PPH and perineal trauma.

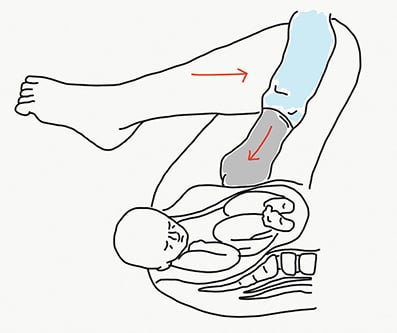

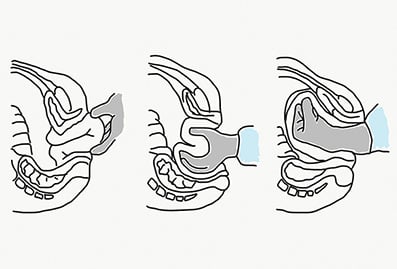

Figure 1. Rubin I manoeuvre.

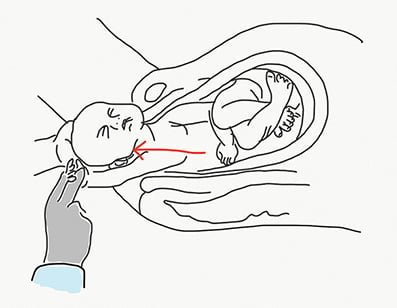

Figure 2. Delivery of posterior arm.

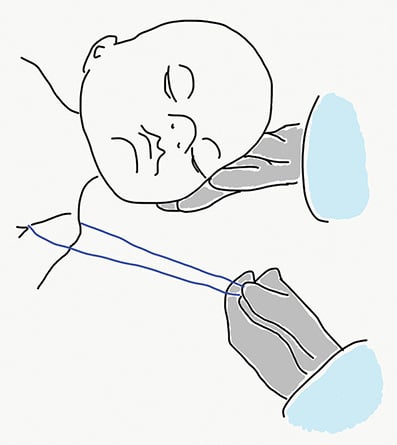

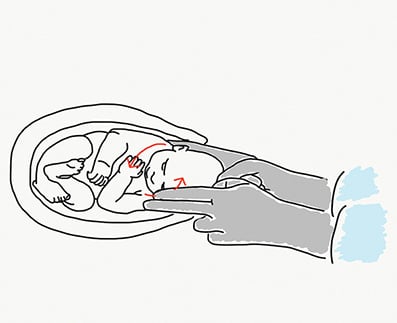

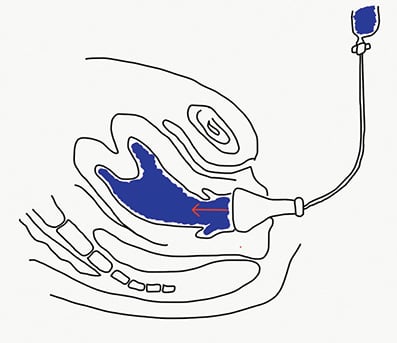

The most crucial steps in management of shoulder dystocia are stating the diagnosis to the room, directing the call for help and commencement of initial management, which is to improve favourability of pelvic diameters in relation to bisacromial diameters. Gaskin (‘all fours’) or McRobert’s manoeuvre (‘knees to nipples’ position) may resolve up to 90% of shoulder dystocia7 and the former can allow delivery of the posterior shoulder. Subsequent suprapubic pressure with continuous pressure or slight rocking motion may allow the anterior shoulder to dislodge from under the pubic symphysis (Rubin I) (Figure 1). Delivery of the posterior arm by flexing the elbow and gently pulling the arm from the vagina allows the anterior shoulder to be delivered, and is recommended as a first-line internal manoeuvre (Figure 2).8 Posterior axillary sling traction with an infant feeding tube has been described to ‘hook’ the posterior shoulder and deliver this first (Figure 3). Rotating the anterior and/or posterior shoulders using Wood’s corkscrew manoeuvre, which may be added to Rubin II manoeuvre, or the reverse Wood’s screw manoeuvre (Figure 4) can effect delivery. Rescue manoeuvres, such as the Zavanelli manoeuvre (pushing the fetal head up to deliver by caesarean) or purposeful cleidotomy or symphysiotomy, may be considered as last resort.

Figure 3. Posterior axillary sling traction.

Figure 4. Wood’s screw maneouvre.

Many clinicians will use mnemonic devices, such as HELPERR9 or similar, to ensure they maintain a systematic approach – the goal being timely relief of obstruction with the least morbidity to mother and child. This can require some quick thinking and may be done in any order. It should be remembered that an episiotomy helps only to allow access but will not relieve what is a bony obstruction. Following a shoulder dystocia, PPH should be anticipated along with the requirement for neonatal resuscitation, careful perineal and PR examination and after care.

Cord prolapse

Cord prolapse occurs when the umbilical cord descends with or before the presenting part of the fetus, with an incidence of 0.1–0.6%,10 and necessitates immediate birth. The outcome of undetected or mismanaged cord prolapse can be dire, with fetal hypoxia occurring secondary to cord occlusion. Cord prolapse should be suspected when there is abnormal (especially sudden) fetal heart rate pattern with ruptured membranes: in particular, soon after spontaneous or artificial rupture of membranes.

Cord pressure should be relieved by elevating the presenting part while preparations are made for an emergency caesarean section (or assisted vaginal birth if birth is imminent). While this is done, the woman should be positioned in a deep knees-to-chest position on all fours with their bottom in the air, or on their left side, with their head lower than the pelvis.

In many rural settings, a delay in transfer to theatre for caesarean section should be expected and planned for. In any setting, a cord prolapse box or trolley can be equipped with an indwelling urinary catheter, saline bag and giving set, ready to instil 500ml into the maternal bladder to lift the presenting part off the cord. A full bladder may allow a spinal anaesthetic to be used instead of a general anaesthetic, if fetal heart rate permits, improving safety for the mother.

Uterine inversion

Uterine inversion is a rare obstetric emergency where the fundus turns into the uterine cavity with potential profound ensuing neurogenic and hypovolaemic shock. The most well-established cause of uterine inversion is early or excessive traction being applied to the umbilical cord before separation of the placenta. Other risk factors include uterine atony, fundal implantation of an adherent placenta, manual removal of placenta, precipitate labour, short umbilical cord, placenta praevia and connective tissue disorders.11

Early detection is imperative to enable immediate manual replacement and resuscitation, with planning to manually remove the placenta only when in a safe environment, where placental adhesive disorder and obstetric haemorrhage can be managed. If cervical shock is evident, atropine should be considered.

Signs include loss of a palpable uterine fundus, an abnormal soft mass on vaginal examination, a uterine fundus visualised externally or any time there is shock disproportionate to haemorrhage.

Figure 5. Johnson’s manoeuvre.

Johnson’s manoeuvre (Figure 5) is first line – grasping the uteroplacental mass, inserting the hand and two-thirds of the forearm into the vagina and raising the fundus above the level of the umbilicus to relax the cervical ring, allowing the passage of fundus through the ring.12 A uterine relaxant can be given to aid manual replacement. If manual replacement fails, the vagina can be filled with warm sterile water (Figure 6) to distend the vagina and push the fundus upwards using hydrostatic pressure (O’Sullivan’s method). Surgical methods may be used, such as incising the cervical ring to allow manual replacement, or laparotomy to pull the uterus cephalad by grasping the round ligaments (Huntington and Haultain procedures).13 14

Figure 6. O’Sullivan’s method.

Document, discuss, debrief, develop

If staff numbers allow, it is ideal to allocate the role of scribe. This person has an important purpose in keeping track of medications given and time elapsed, and can sometimes act as liaison between the team, directly managing the emergency and support staff (e.g. haematologist, transfusion lab, or retrieval services), as well as allowing contemporaneous documentation.

A discussion about the clinical issues, actions taken, follow up and implications for the future with the woman and her supports at the time of the event is essential, and with most serious events this would be revisited the following day and in a few weeks’ time. This is important to aid understanding from the patient’s perspective and reassure, as an evolving emergency (even when well managed clinically) can appear rapid, confusing, and frightening for those directly experiencing it. Post-traumatic stress disorders are a potential consequence of birth trauma and debrief may reduce mental distress.15

Staff, too, may need added support after a critical incident and a formal process to review and discuss emotional responses and team function should be offered.16 Standardised morbidity and mortality review to capture critical events are needed to identify and support continual quality improvement and inter-professional learning. This is an opportunity to reflect on how best to collaborate as a multidisciplinary team, considering systemic, clinical and human factors as small cogs in the giant wheel of maternity healthcare.

References

- Singh A, Nandi L. Obstetric Emergencies: Role of Obstetric Drill for a Better Maternal Outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62(3):291-6.

- Kumar A, Sturrock S, Wallace E, et al. Evaluation of learning from Practical Obstetric Multi-Professional Training and its impact on patient outcomes in Australia using Kirkpatrick’s framework: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e017451.

- Winter C, Crofts J, Laxton C, et al (Eds) Sowter M, Weaver E, Beaves M. PROMPT PRactical Obstetric MultiProfessional Training Course Manual, Australian and New Zealand Edition. 2008.

- Rodis JF. Shoulder dystocia: Intrapartum diagnosis, management, and outcome. 2019. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/shoulder-dystocia-intrapartum-diagnosis-management-and-outcome

- Leung T, Stuart O, Sahota D, et al. Head-to-body delivery interval and risk of fetal acidosis and hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in shoulder dystocia: a retrospective review. BJOG. 2010;118(4):474-9.

- Wood C, Hing Ng K, Hounslow D, Benning H. Time – An Important Variable in Normal Delivery. BJOG. 1973;80(4):295-300.

- RCOG. Green-top Guideline No. 42. Shoulder Dystocia. 2012. Available from: www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg_42.pdf

- Winter C, Crofts J, Laxton C, et al (Eds) Sowter M, Weaver E, Beaves M. PROMPT PRactical Obstetric MultiProfessional Training Course Manual, Australian and New Zealand Edition. 2008.

- Politi S, D’Emidio L, Cignini P, et al. Shoulder dystocia: an Evidence-Based approach. J Prenat Med. 2010;4(3):35-42.

- RCOG. Green-top Guideline no. 50. Umbilical Cord Prolapse. 2014. Available from: www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-50-umbilicalcordprolapse-2014.pdf

- Bhalla R, Wuntakal R, Odejinmi F, Khan R. Acute inversion of the uterus. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2009;11(1):13-18.

- Johnson AB. A new concept in replacement of the inverted uterus and report of nine cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1949;57:557–62.

- Huntington JL, Irving FC, Kellogg FS, Mass B. Abdominal reposition in acute inversion of the puerperal uterus. Am J Obstet and Gynaecol. 1928;15:34-8.

- Haultain FWN. The treatment of chronic uterine inversion by abdominal hysterectomy, with a successful case. Br Med J. 1901;2:974.

- Axe S. Labour debriefing is crucial for good psychological care. Br J Midwifery. 2000;8:626-31.

- Blacklock E. Interventions Following a Critical Incident: Developing a Critical Incident Stress Management Team. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2012;26(1):2-8.

Leave a Reply