Women are delaying childbearing more today than ever before. In Australia, birth rates for women aged 40 and older were at 12.9/1000 births in 2017, compared with 4.4/1000 births in 1980.1 Improved access to higher education and career opportunities, and a desire to achieve career, educational and financial goals, are some of the biggest reasons cited for later age of childbearing. Reduced relationship stability and later partnering, as well as improved access to contraception and assisted reproductive technology (ART), are other factors.

The term advanced maternal age (AMA) is not clearly defined internationally and varies in the literature between 35–40 and above. There are multiple consequences of AMA, which we will now address.

Fertility

Due to reduced oocyte quality and quantity, fertility begins to fall significantly from around age 32, with a more rapid decline from around age 37. After the age of 35, the advice is for women to seek fertility help after six, rather than twelve months of trying to conceive. For some women of AMA, IVF with their own eggs is not successful and sadly, that will be the end of their fertility journey. Others may be willing to consider donor oocytes. Past age 40, live birth rates per Australian IVF cycle are 1.4–12.5% with autologous oocytes, but improve to 28.6–42.5% with donor oocytes.2

Early pregnancy

AMA is associated with increased rates of:

- Spontaneous miscarriage

- Chromosomal abnormalities, including aneuploidy

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Multiple pregnancy

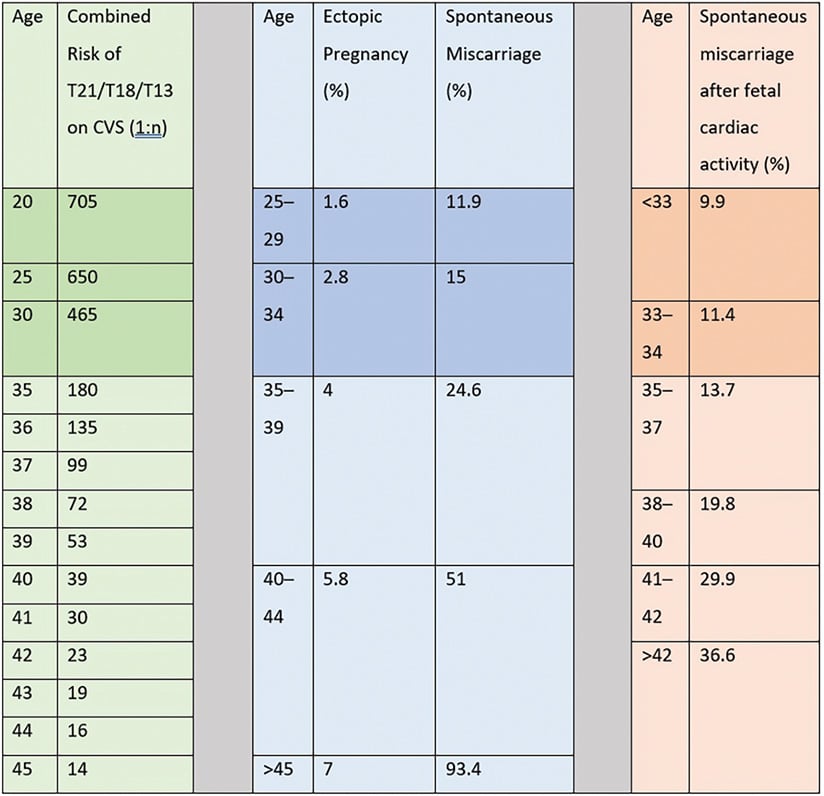

Chromosomal abnormalities are more common in embryos of women of AMA, attributed to the longer time their oocytes have been suspended in Metaphase 1, where DNA is vulnerable to oxidative stress and telomeres to damage. Chromosomally abnormal embryos explain the majority of the increased spontaneous miscarriage rate seen in AMA (Figure 1).

The risk of a baby with aneuploidy increases drastically from age 35 (Figure 1); aneuploidy screening should be offered, either non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) or combined first trimester screening.

The increased risk of ectopic pregnancy is likely due to an accumulation of risk factors over time, such as multiple sexual partners, pelvic infection and tubal pathology.

AMA increases the risk of multiparity (rising FSH levels can result in more than one dominant follicle) but today is mostly due to ART. Australia has an excellent record internationally for low rates of multiparity in the context of ART, with consensus of single embryo transfers when possible.

Figure 1. First trimester complications of AMA. Adapted from Fretts et al.

Second and third trimester complications

As women age, they naturally have higher rates of comorbidities that can complicate pregnancy, such as diabetes, hypertension and obesity. This highlights the importance of pre-conception optimisation of these conditions; however, even after considering comorbidities, parity and multiparity, AMA in otherwise low-risk women is associated with increased rates of:

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (RR 4.1)3 4

- Gestational diabetes (OR 3.7 AMA ≥40)5

- Placenta praevia (RR 3.16), accreta and abruption6

- Pulmonary embolism (OR 2.4 AMA ≥40) 7

- Fetal growth restriction (OR 1.5 AMA ≥40) 8

- Iatrogenic and spontaneous preterm birth (OR 1.5 AMA ≥40)9

Traditional thinking has sought to attribute much of the above on the abnormal placentation seen as women age.10 A greater body of work now suggests the primary event behind defective placentation is a maladaptive cardiovascular response to pregnancy. Studies demonstrate that in pregnancy in women of AMA, uterine artery resistance and peripheral vascular resistance increase and the vascular endothelial cell function diminishes.11

The increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is also due to the fact that pancreatic B-cell function and insulin sensitivity fall with age.12

Stillbirth

The relationship between AMA and stillbirth is well established and consistently observed. A large meta-analysis of 44 million births gave an OR of 1.75 for age ≥35.13 The risk increases further as women age. Prevalence of stillbirth is 0.9% among mothers aged 40–49 years and 1.0% age 50 years and over, compared to 0.5% aged 20–39 years.14 The risk increases with advancing gestation, such that women ≥40 years of age have the same risk of stillbirth at 39 weeks, as 20-year-olds have at 41 weeks of gestation. As a result, most centres will advise induction of labour (IOL) after 39 weeks for AMA.

Intrapartum complications

AMA is associated with increased rates of:

- Caesarean section (CS) (RR 4.1)15

- Postpartum haemorrhage

The increased CS rate is partly attributed to pregnancy complications and a lower threshold for elective or emergency CS. However, independent of this, AMA increases risk of labour dystocia and CS for fetal distress.16

Maternal mortality and long-term maternal cardiovascular complications

Several studies demonstrate an increase in ICU admission and maternal death in women of AMA. Risk factors in the context of AMA are cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, obesity and operative delivery.17 18

After AMA pregnancy, CVD may be higher. It is well established that women who experience pre-eclampsia toxaemia (PET) are twice as likely to die of CVD later in life. In addition, it may be that pregnancy at AMA adds additional stress to an aging cardiovascular system.19

Short birth interval may further increase risk. Women of AMA ≥35 years who had six-month interpregnancy intervals compared with 18-month intervals had higher rates of severe maternal morbidity or mortality. This was not seen in younger women.20

Parenting

Finally, some good news? Increasing maternal age is associated with improved health and development in their children, including cognitive ability. Children of older parents have described benefits, including the devotion, patience and attention of their parents, as well as their emotional and financial stability.21

Pregnancy management tips for AMA

- Preconceptual counselling: warn of risk, optimise medical conditions, preconceptual folic acid and iodine

- Avoid multiple pregnancy if undertaking ART

- Aneuploidy screening: consideration to NIPT given its higher sensitivity and specificity

- Low dose aspirin from 12–36 weeks

- Consider screening for GDM in first trimester

- Warn about risks of GDM, PET and plan a model of care accordingly

- Consider growth ultrasounds

- Make a plan for stillbirth risk prevention: discuss other stillbirth risk factors, encourage smoking cessation, discuss fetal movement patterns and side sleeping

- Make a plan for delivery: IOL at 39 weeks strongly advised. Very advanced maternal age may wish to choose elective CS

- Discuss interpregnancy interval (from birth to conception) of 12–18 months due to reduction in maternal death22

Summary

Women at AMA face a wide range of significantly increased risks across all stages of the fertility, birth and pregnancy journey. The societal factors that have led to the rise in AMA (that is, educational, career and financial advancement in women) are advances our feminist forbearers fought hard for and that we certainly would not want to relinquish. Firstly, as clinicians working with women, our role is to make pregnancy as safe as possible. Secondly, we should be educating women and society about the increased risk AMA brings to a pregnancy. These risks are widely underestimated by the public. Finally, as a society (and a training college) we need to ask ourselves: how can we create opportunities for women to become mothers earlier without disadvantaging them from an educational, career or financial point of view?

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Births, Australia 2017. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018.

- Hogan R, Wang A, Li Z, et al. Having a baby in your 40s with assisted reproductive technology: The reproductive dilemma of autologous versus donor oocytes. ANZJOG. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13179.

- Pinheiro R, Areia A, Mota Pinto A, et al. Advanced Maternal Age: Adverse Outcomes of Pregnancy, A Meta-Analysis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32(3):219-26.

- Sauer M. Reproduction at an advanced maternal age and maternal health. Fertility and Sterility. 2015;103(5):1136-43

- Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, et al. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186287.

- Martinelli K, Garcia EM, Santos Neto E, et al. Advanced maternal age and its association with placenta praevia and placental abruption: a meta-analysis. Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2018;34(2):e00206116.

- Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, et al. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186287.

- Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, et al. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186287.

- Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, et al. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186287.

- Torous V, Roberts D. Placentas From Women of Advanced Maternal Age: An Independent Indication for Pathologic Examination? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2019-0481-OA.

- Cooke C, Davidge S. Advanced maternal age and the impact on maternal and offspring cardiovascular health. American Journal of Physiology. 2019;317(2):H387.

- Pinheiro R, Areia A, Mota Pinto A, et al. Advanced Maternal Age: Adverse Outcomes of Pregnancy, A Meta-Analysis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32(3):219-26.

- Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, et al. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186287.

- Dongarwar. Stillbirths among Advanced Maternal Age Women in the United States: 2003–2017. Int J MCH and AIDS. 2020;9(1):153-6.

- Sauer M. Reproduction at an advanced maternal age and maternal health. Fertility and Sterility. 2015;103(5):1136-43

- Kortekaas JC, Kazemier BM, Keulen JKJ, et al. Advanced maternal age: A national cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13828.

- Pinheiro R, Areia A, Mota Pinto A, et al. Advanced Maternal Age: Adverse Outcomes of Pregnancy, A Meta-Analysis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32(3):219-26.

- Sauer M. Reproduction at an advanced maternal age and maternal health. Fertility and Sterility. 2015;103(5):1136-43

- Cooke C, Davidge S. Advanced maternal age and the impact on maternal and offspring cardiovascular health. American Journal of Physiology. 2019;317(2):H387.

- Schummers L, Hutcheon J, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Association of Short Interpregnancy Interval With Pregnancy Outcomes According to Maternal Age. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1661-70.

- Fretts RC, Wilkins-Haug L, Simpson LL. Effects of advanced maternal age on pregnancy. UpToDate, 2019. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/effects-of-advanced-maternal-age-on-pregnancy

- Schummers L, Hutcheon J, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Association of Short Interpregnancy Interval With Pregnancy Outcomes According to Maternal Age. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1661-70.

Leave a Reply