After working in global health for over 20 years outside of Australia, what continues to disturb me are the huge inequities between and within countries. The ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’. There are those that can and do access healthcare, including sexual and reproductive healthcare, and then there are those who just cannot due to a variety of reasons including prohibitive out-of-pocket costs they would incur for seeking care, and a lack of essential infrastructure such as lack of roads and transport to take them to a health facility including in an emergency. These imbalances in access to quality and respectful care and health system fundamentals that I had taken for granted, like well trained and supported health professionals, functioning supply chains for life saving medicines and referral systems to ensure women would get the care they need to prevent them from dying during childbirth, continue to drive the work we do.

Ending preventable maternal and newborn mortality remains an unfinished agenda in the Asia-Pacific region, with 10 women dying every hour in pregnancy and childbirth. Many countries will need to double, or more than double, their current annual rates of reduction of mortality to ensure sufficient progress toward national targets and the global Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG) with its vision of optimal health for all. Even if considerable progress was made between 1990 and 2017, with countries in Asia-Pacific reducing the regional maternal mortality ratio (MMR) by 56% (compared to a 35% reduction in maternal mortality at the global level), absolute numbers of maternal deaths remain staggering in many countries of the region and a call to act must be sounded louder, and more urgently, than ever.

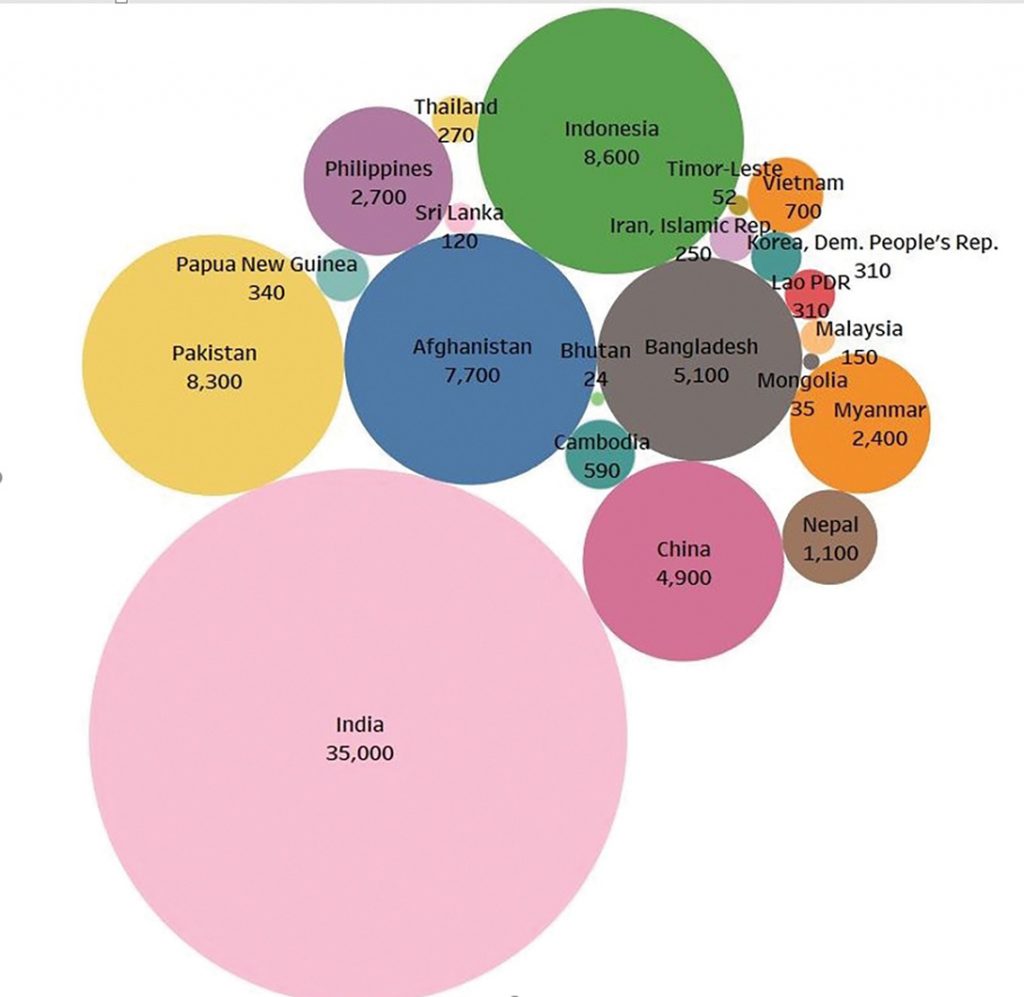

Figure 1. Estimated numbers of maternal deaths in countries of Asia-Pacific in 2017.

Source: UNFPA Asia Pacific Regional office analysis.

The majority of countries in the Asia-Pacific region are in Stage 3 of the obstetric transition,1 a complex stage where the ‘tipping point’ occurs. In these countries, we can see continued high maternal mortality due to direct obstetric causes. The health service provision characteristics of ‘too much too soon and too little too late’ are all too prevalent and we have some countries where women struggle to access a lifesaving C-section, and then others where it has become the norm. We are also seeing other consequences like iatrogenic fistula. Although a greater proportion of women are able to reach facilities for delivery, access remains an issue for much of the population. The role of referrals and intrahospital issues, like overcrowding and lack of emergency stabilisation prior to referral, is critical as we can see women often die due to delays in receiving adequate care once they reach the health facility. In these countries, the focus needs to be on quality of care, including skilled birth attendance by qualified midwives, and access to emergency obstetric and newborn care, including the life-saving functions that can only be performed by properly trained and equipped obstetricians and anaesthetists, as this is a major determinant of health outcomes in this stage.

The remainder of countries in the region, including Maldives, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, are in Stage 4 of the obstetric transition. This stage, which is characterised by moderate to low maternal mortality, low fertility and indirect causes of death, particularly non-communicable diseases like hypertensive disorders, demands greater attention to the cause of mortality. In this stage, over medicalisation is a threat to quality and health outcomes. The focus for countries in Stage 4 needs to be on improving the quality of care, eliminating delays within the health system, addressing over medicalisation and target pockets of inequity within the country.

COVID-19 and maternal mortality in Asia-Pacific

One of the greatest concerns since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the potential and actual decrease in women seeking care during their pregnancy and delivering safely with a skilled birth attendant in a health facility, as we know these have a significant impact on maternal and newborn mortality. Ministries of Health, global health agencies including UNFPA and civil society and non-governmental organisations have worked hard to improve access to these services in past decades, and now we see these are threatened by COVID-19 related disruptions.

Antenatal attendance has decreased in many countries in the Asia-Pacific region, and there are variations in patterns of attendance within countries, highlighting persisting inequities. The result is that high-risk pregnancies and danger signs for the mother and fetus are not detected and thus not acted on quickly enough to save the life of the mother and prevent preterm birth and stillbirths.

Some women are choosing to deliver their babies at home without a skilled birth attendant and with no emergency ambulance system for referral in place. This will result in maternal deaths and sets countries back in terms of reaching the SDG targets on maternal health.

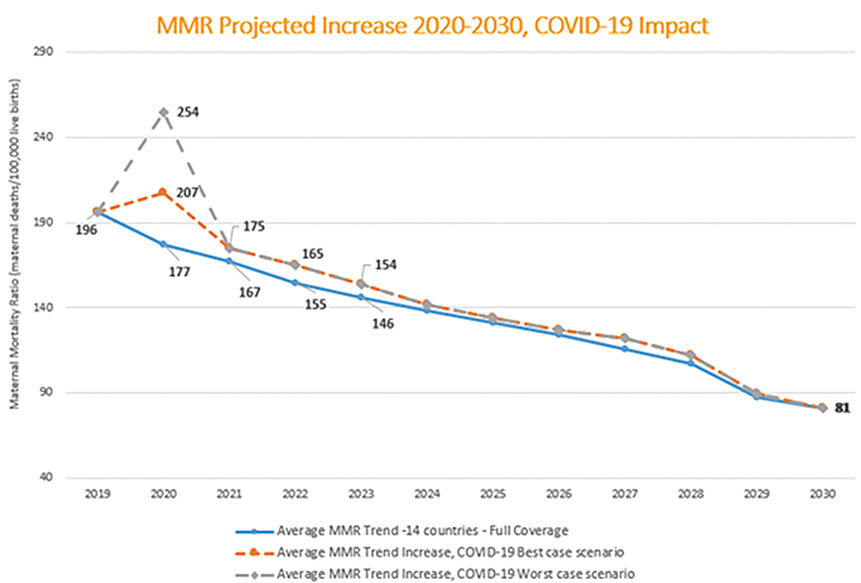

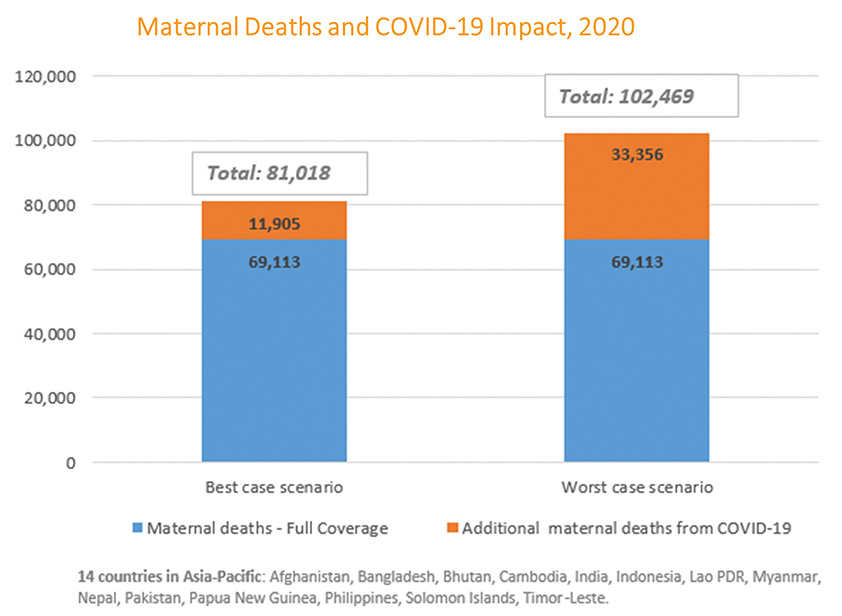

The graph below uses modelling estimates to project the impact of reductions in percentage of deliveries conducted in an institution and with a skilled birth attendant in 14 high-priority countries of the Asia-Pacific region. The graph models a potential decrease of 20% or 50% (best- or worst-case scenarios) in those services, compared to the latest average baseline. In both scenarios, the risk countries are facing for increased maternal deaths is clear, if we do not act urgently to ensure all women seek care, and that services are provided by skilled birth attendants in properly staffed and equipped hospitals.

Figure 2. Potential increase in maternal mortality ratios and maternal deaths in 2020, due to a decrease in access

to skilled birth attendance and deliveries in health facilities. Source: UNFPA Asia Pacific Regional Offices analyses.

Figure 3. Potential increase in maternal mortality ratios and maternal deaths in 2020, due to a decrease in access

to skilled birth attendance and deliveries in health facilities. Source: UNFPA Asia Pacific Regional Offices analyses.

The right to respectful maternity care at all times

‘All pregnant women, including those with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infections, have the right to high-quality care before, during and after childbirth. This includes antenatal, newborn, postnatal, intrapartum and mental healthcare.’ World Health Organization, 2020.

Reductions in numbers of women seeking care have been caused by both fear around the perceived risks of infection with COVID-19 if a pregnant woman seeks care at a health facility, and due to the various interpretations or laws around restricted movement or ‘lockdown’. Pregnant women’s access to health facilities has also been reduced during COVID-19 due to changes in availability of public transport including local motos, rickshaws and tuk-tuks as options to transport pregnant women to facilities. Pregnant women with disabilities face even greater barriers and restrictions in trying to access health services at this time.

Financial barriers to access healthcare have been exacerbated due to COVID-19, particularly in countries where social protection does not cover pregnancy care and also where not all segments of the population have financial risk protection schemes to enable them to access healthcare without catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditure. Many people have lost jobs and with no stable source of income and continuing living expenses for families, pregnant women’s access to healthcare during pregnancy is threatened.

The impact on acute care services in settings with under-resourced health systems has been substantial. Countries and all stakeholders need to make efforts to maintain and protect maternal health systems. Maternity services should continue to be prioritised as an essential core health service and, within that, maternity care providers and the maternal health workforce need to be protected so that they can provide safe and effective maternity care to women.2

Ending preventable maternal mortality in every country in our region remains of critical importance and deserves continued attention and technical and funding support for many countries. Prioritising the most left behind populations requires substantial effort and focus of all actors. We have come a long way in the last decade but we have much more work to do if we are to reach the goals and targets set in the SDGs and in global and national strategies to end preventable maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity. The challenge of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic has placed additional strain on the health systems in countries and made our efforts to end preventable maternal mortality even more complex than before. The good news is that we know what must be done – even if that is not easy! Tailored and country-specific approaches are required to address inequities within and between countries and a focus beyond coverage of health services to quality – even during a pandemic. Let us strive all the harder then, as we traverse this Decade of Action in achieving the SDGs that underpin the 2030 Agenda with their vision of truly leaving no one behind.

References

- Souza JP, Tunçalp, Ö, Vogel, JP, et al. Obstetric transition: the pathway towards ending preventable maternal deaths. BJOG. 2014;121(Suppl. 1):1-4.

- UNFPA. COVID-19 Technical Brief for Maternity Services. 2020. Available from: https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/publications/covid-19-technical-brief-maternity-services

Leave a Reply